The theater is at its full capacity. The musicians are in place as the orchestra conductor starts to wave his arms in time with the image on the screen. There, little red dots emerge from a black background. They slowly widen and turn into capital letters: The word KOYAANISQATSI takes over. Keyboard notes evoking a church organ underline the mystery of the term and suit the dramatic hard-edged-typography. It is a Friday afternoon, February 23, 2018, in the Bass Concert Hall of the Texas Performing Art Center of The University of Texas, at Austin. The occasion is the screening of Godfrey Reggio’s 1982 film, accompanied by the live performance of The Philip Glass Ensemble playing its original score music.

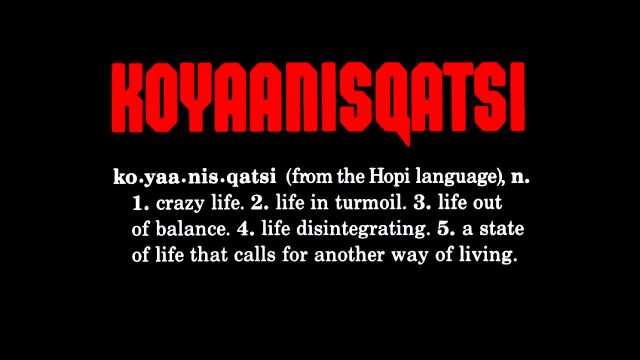

Featured for the first time to an ample public in the 1982 New York Film Festival, Koyaanisqatsi is an audiovisual art piece without dialogue or voiceover, deprived of any explicit narrative, that is nowadays a cult classic. It opens with a shot of the Holy Ghost Panel in Horseshoe Canyon, Utah, a human trace dated between 400 AD and 1100 AD. Then, footage of imposing natural landscapes and wildlife of the United States’ Southwest is followed by images of urban spaces: construction, crowded streets, demolitions, technology of the time, and so on. The collage escalates in its pace along with the music: flutes, clarinet, trombone, viola, tuba, keyboards and vocals from time to time repeat the word “koyaanisqatsi” in a low pitched ceremonial tone that creates an apocalyptic atmosphere. The last scenes of the film exhibit the same red letters of the beginning but depicted as an English dictionary entry: “ko.yaa.nis.qatsi (from the Hopi language), n. 1. crazy life. 2. life in turmoil. 3. life out of balance. 4. life disintegrating. 5. a state of life that calls for another way of living.” The piece ends with three sentences translated from “Hopi Prophecies” that were sung during the film. Their content indicates the destruction of the land and the “Day of Purification” to come.

Well received by its first audiences, the movie continues to be screened and studied as an audiovisual experimental piece that influenced many filmmakers and composers. However, little attention has been paid to its Hopi framing. How did Reggio become acquainted with the word “koyaanisqatsi” and the prophecies he cites? Was it something of common knowledge during the mid 70s when he started filming? If so, why? Did Hopi people engage with non-natives at the time? Is this a case of “playing Indian,” as Philip J. Deloria would put it, an appropriation? Did Reggio request permission to use the Hopi knowledge? When asked about it (in our telephone interview), Reggio answers with a ready-made discourse learned over the years:

Let’s take the Graduate Department of Ethnology of any university. People from other cultures use their subjective categories to analyze Indigenous Peoples. So, knowing that, what I did was take the subjective categories of Indigenous Peoples [the Hopi] and use that to analyze the world we live in. I made an inverse relationship of what we do in academia, because I thought their point of view about the world we lived in was more profound than our point of view of it.

This didactic approach may explain his main inspiration, but there is more to the story. It involves a collective movement that started in 1948 and was prominent until the beginning of the nineties, advocated by the “Traditionalist Hopis,” as they were called, or the “Hopi Indian Empire,” their self-chosen name, and Reggio’s own personal sense of mission on Earth. Like many extraordinary events in the human saga, this was a product of being in a specific place at a specific time. The result is a film that encapsulates an important chapter of the history of the relationship between Native and non-native people on the Turtle Island or the United States.

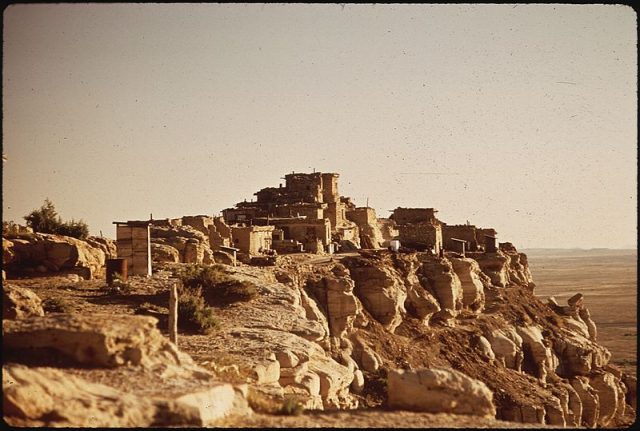

A Mesa Village of Hopi Indians, Arizona (via Wikimedia)

As a Pueblo people, the Hopi’s history goes way back in time, long before the Common Era. Today, they are a sovereign nation that inhabits the northeastern area of Arizona, organized in twelve villages that occupy three mesas. This episode of their existence begins with the extraordinarily cruel act of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 by the United States’ Air Force, near the end of World War II. Among the remote consequences of this attack, one or two years later, a group of Hopi of the Second Mesa at their ceremonial reunions (kivas) started “equating the atomic bomb with a prophetic story about a gourd of ashes which brought destruction when it was cast on the ground,” according to anthropologist Brian D. Haley. By 1948, with the devastation of planet Earth in mind because of human greed, elders and religious leaders of the Second and Third Mesa decided it was urgent to share this prophecy with the “White people” so that everyone could be prepared for Purification Day, the moment when deity of the current fourth world, Maasaw, would come and redeem humanity, creating a new paradise on Earth.

The effort to spread the word on the ancient prophecies is what anthropologist Richard Clemmer designated the “Hopi Traditionalist Movement.” The Hopi agenda, though, was more than a spiritual calling; it was very political. In 1949 they sent President Truman a letter in which they detailed their prophecies and message of awareness, but also their position about land ownership, mineral extraction permits, the cultural and political rights of indigenous peoples, and pending US policies.

With the help of non-Native People, the movement got the attention of conscientious objectors and draft resisters of the Second World War, pacifists, anarchists, spiritual radicals, and, in time, the different counterculture circles of the 1950s, 60s and 70s, including hippies, and even Hollywood stars like Elizabeth Taylor and Jon Voight. One spokesperson, Thomas Banyacya, became well known for his lifetime struggle to get out the Hopi message of environmental destruction, its consequences, and Indigenous People’s rights.

It’s the mid 1970s and Godfrey Reggio does not have a name for the film he is shooting. His co-workers are telling him they are not going to get distribution or financial aid if he does not name it. Reggio had resisted to do so until then, because for him the images were the message. Persuaded, he starts searching for a word “with no cultural baggage, a new word to describe the world.”

When Reggio decided he was going to translate his thoughts onto film, he was building on ideas based on a life of spiritual and social engagement. He spent 14 years, beginning at age fourteen, with the Christian Brothers, a Catholic religious order. In 1963, he started Young Citizens for Action in New Mexico with a group of juvenile street gang leaders. He was dedicated to helping adolescent boys and girls escape these violent communities. But his willfulness to take the Christian Brothers’ educational mission outside, to vulnerable people living in poverty, made the authorities uncomfortable and so, in 1968, he was asked to leave. “The world I lived in prior to knowing Hopis seemed like a world that was upside down,” he says today. His concerns for the ways in which humans were living their lives, and inhabiting the Earth with its technological, social and environmental transformations are embedded in the film.

Living in Santa Fe, Reggio was near the Hopi reservation and had friends that were “Hopi devotees,” as he calls them. They insisted on the connections between his creative project and the Traditional Hopi Movement’s prophecies. He met David Monongye, one of the Hopi spokesmen of Hotevilla, by giving him a ride from the reservation to a doctor’s appointment and they became friends. Reggio liked the idea of naming his film with an originally non-written language to evoke his argument that the literate culture he lived in was no longer a good describer for the insanity he saw all around. Thus, he contacted the linguist Ekkehart Malotki, who knew the Hopi language, and his Hopi co-worker Michael Lomatuway’ma. They introduced him to the word koyaanisqatsi, a concept that nailed his awareness. Reggio went to David Monongye for permission. “David said it’s an ancient word,” recalls Reggio today, “a word that’s not in popular use. He didn’t talk much about it, but he said the definition we had, took the meaning of the word.”

Reggio not only asked for Monongye’s opinion, he also went through two more examinations by clan leaders of other villages: first by Mina Lansa, the traditional leader of Old Oraibi, and her husband John, then by a group of members of the 2nd Mesa. Reggio felt as he had gone through an ecclesiastical interrogation once again, and in a language he couldn’t understand, but with better results. All of them gave him consent. When the film was finished, he screened it at the cultural center of the reservation, in addition to renting buses to bring Hopis to the exhibition of the film in Santa Fe, where Monongye introduced it. Today, Reggio states he has never had a complaint from the Hopi peoples and he has continued to use their language in his qatsi (life) trilogy, with the films Powaqqatsi (1988), life in transformation, and Naqoyqatsi (2002), life as war. Lately the word has had a new revival. Historian James F. Brooks uses it in his book Mesa of Sorrows (2016) to depict the telling of the mesa massacre of the 1700, when Hopis killed Hopis.

Reflecting on why, of all the possibilities, he chose the Hopi language, and with it their culture and history, to frame his thoughts, Reggio says today: “What defines my relationship to the Hopi is that I was one person with a mission that was their mission too: To show the world in another way.”

This article drew on my telephone interviews with Godfrey Reggio on March 5 and April 19, 2018, and the following sources:

Brian D. Haley, “Ammon Hennacy and the Hopi Traditionalist Movement: Roots of the Counterculture’s Favorite Indians,” Journal of the Southwest, Vol. 58, No. 1, Spring 2016.

Armin W. Geertz, The invention of Prophecy (University of California Press, 1994).

Richard O. Clemmer, Roads in the Sky: The Hopi Indians in a Century of Change (Westview Press, 1995)

You may also like:

For Native Americans, Land Is More Than Just the Ground Beneath Their Feet by Kelli Mosteller

Mark Sheaves reviews Playing Indian by Philip Deloria (1999)

The Public Archive: Doing History Online and in Public