In Eric Remarque’s 1921 novel, The Road Back, a group of veterans (now enrolled as students at a local university in Germany) quietly seethe at the back of a classroom while their professor eulogizes their fallen comrades. The professor’s platitudes cause them to wince, but his romanticism of death makes them boil over in angry laughter. The professor speaks about how the fallen have entered a “long sleep beneath the green grasses.” After the laughter subsides, the veteran Westerholt spits out a tirade: “in the mud of shell holes they are lying, knocked rotten, ripped in pieces, gone down into the bog—Green grasses! … Would you like to know how young Hoyer died? All day long he lay out on the wire screaming, and his guts hanging out of this belly like macaroni … now you go and tell his mother how he died.” The scene dramatically underlines the painful tension that arises in a culture between realistic and romantic memory after a dreadful war.

Like Remarque’s The Road Back, Faust’s This Republic of Suffering is a cartography of sorts—mapping how people respond to trauma, defeat, and above all mass death. Faust’s originality is grounded in a rudimentary social fact—that during the civil war, a lot of people died (over 620,000) and those who lived had to deal with it. In a similar-sized conflict today, that would mean about 7 million Americans or 2 percent of the population perishing. For Faust, the sheer magnitude of this number meant that “the United States embarked on a new relationship with death.”

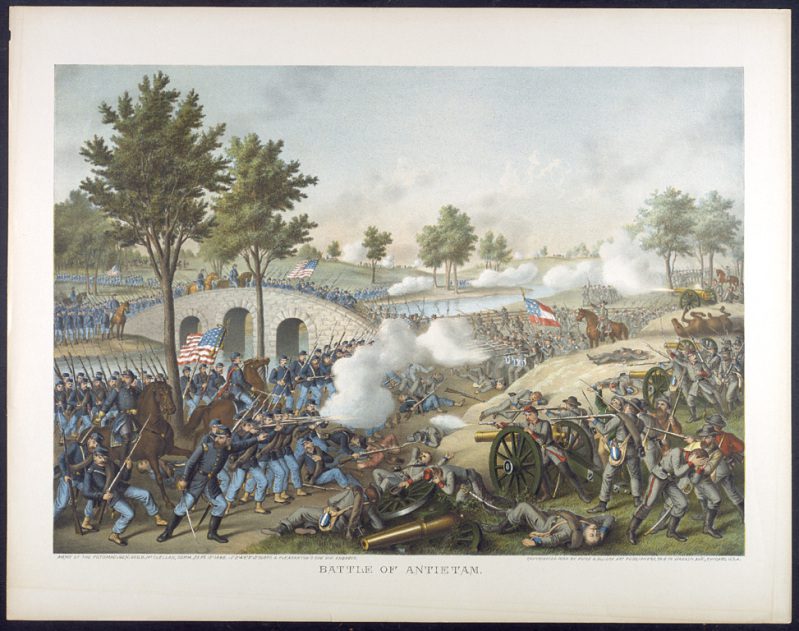

The elegance of Faust’s concept is illustrated by her simple chapter titles: Naming, Numbering, Burying, Accounting. Her point here is that to respond to death is to work. It takes time, thought, effort, and energy to name, number, bury, and account for the dead. But this work can also be figurative as alluded to in chapters titled Realizing, Believing and Doubting, Surviving: “the bereaved struggle to separate themselves from the dead … [they] must work to understand and explain unfathomable loss.” Like Remarque’s soldiers, civil war Americans struggled to come to terms with the reality of death—not just its sheer volume, but also its individual reality. In “Dying” Faust outlines the established concept of the “good death” in antebellum American culture, which she claims was prevalent across classes and regions. The “good death” was peaceful and relatively painless, with its resolute subject at home, full of religious faith and surrounded by their family. The Civil War exploded such notions, and left society reeling. Soldiers might die in tremendous pain, far from home amidst the chaos of combat. Corpses were often left strewn across battlefields or hastily buried. Exploding shells might mean there was little left of a person to bury.

In wake of the death of the “good death,” Faust captures a culture in transition, forced to innovate at the level of the individual, the market, and the institution. At the individual level, Faust perceives a challenge to traditional religious belief. Whether evangelical or traditional in their Christian affiliations, most Americans believed in an afterlife that assumed the restoration of their body in a heavenly realm, contingent upon a mature profession of faith in the present life. But how was one’s body to be resurrected if it were blown to bits? Were teenager soldiers as accountable for their beliefs as their elders? Thus, “the traditional notion that corporeal resurrection and restoration would accompany the Day of Judgment seemed increasingly implausible to many Americans who had seen the maiming and disfigurement inflicted by this war.”

Republic of Suffering isn’t a religious history, but it is certainly a book about the self. What most Americans came to believe about the self was based not on “scripture and science but on distress and desire.” Works such as Elizabeth Phelp’s The Gates Ajar (only Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold more books in the 19th century) catered to death as effectively as did the churches. In this sense, Faust’s book has as much to say to scholars of secularization as it does to cultural historians. Americans yearned for a more benevolent God—one who respected personhood beyond the grave, and one who operated a liberal gate policy—so they invented one. Other needs arose as well. Embalmers and morticians, burial scouts and gravediggers, coffin makers, private detectives, and journalists all found work during the Civil War. They were entrepreneurs in an economy of death, an ontological marketplace where a new concept of the self was born—a self that (with the help of God and the market) would survive the transition from life to afterlife.

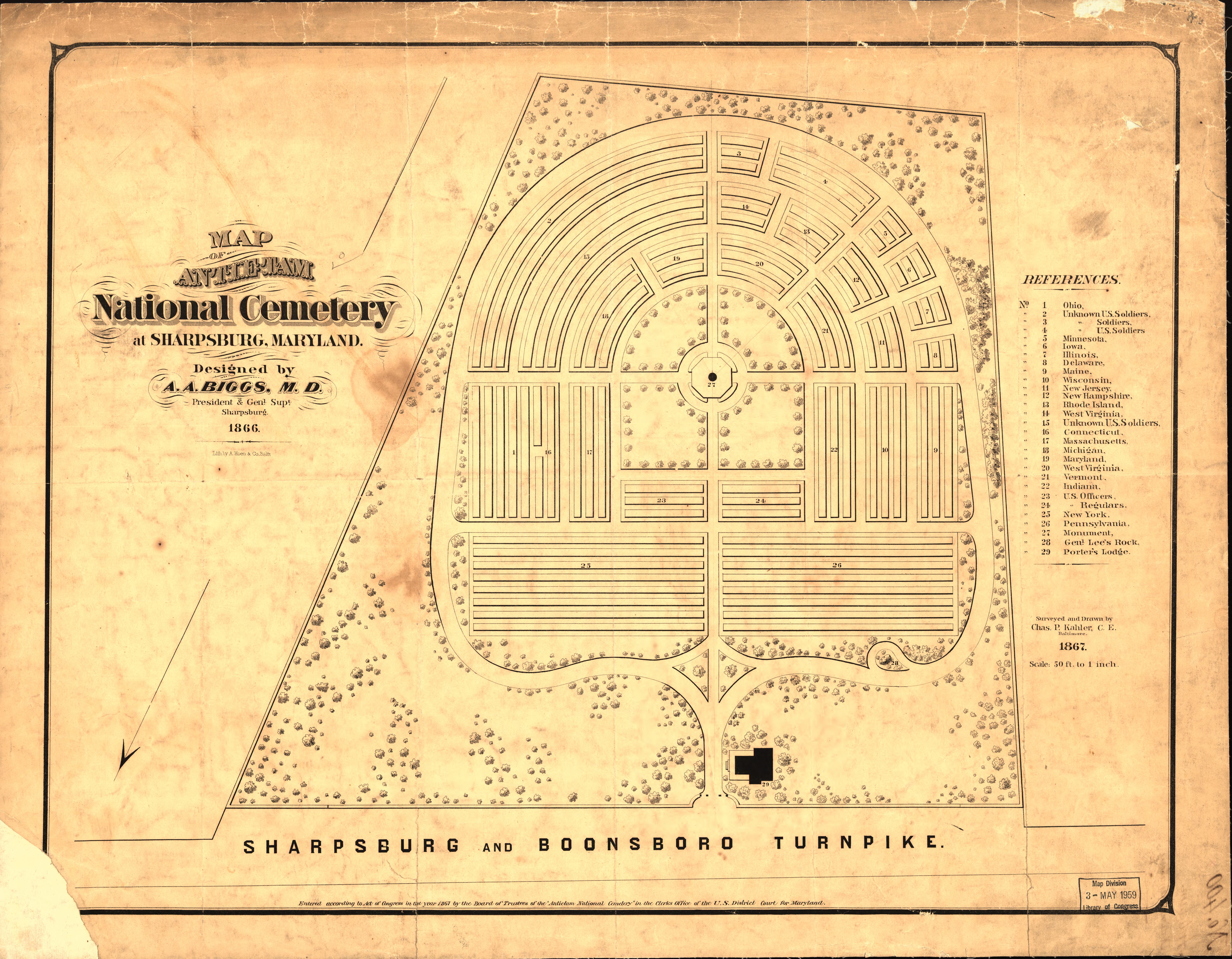

In addition to the market, government too had to respond to the new reality of mass death. There was the basic need for national cemeteries and provisions for the burial of unknown soldiers. However, Faust sees beyond such responses to detect an acceleration of nation-building: “execution of these newly recognized responsibilities would prove an important vehicle for the expansion of federal power that characterized the transformed postwar nation.” The significance of the sacrifices of the enlisted pivoted from being individual, local, or religious to being national.

Or was this simply the case on the Union side? Faust tends to flatten the experiences of northern and southerners into the category of “Americans.” However, the South lost around 18% of its fighting-age men, compared to 6% in the North. Surely this made a difference, but Faust chooses not the broaden her inquiry in this direction. Furthermore, for all the book’s originality, it lacks historiographical context. In particular, Faust chooses not to engage directly with the scholarship on trauma. Perhaps doing so would have disrupted a book that brings letters, memoirs, photographs, and diaries to life. On the other hand, by relying mostly upon written sources, Faust limits herself to the most articulate people of the past. How might we better understand the emotional life of those who left little historical trace, those like Remarque’s Westerholt who responded with angry laughter? Nevertheless, This Republic of Suffering provides a moving snapshot of Americans responding to calamity. Using death as a lens furnishes Faust with an original and effective framework for understanding the more national, more secular, and more nostalgic America that arose during the Gilded Age. It reasserts the Civil War as a truly transformative event in American history, that should be seen not only as the midwife of modern America but also as a truly, chillingly modern conflict.

More from Ben Wright:

Fandangos, Intemperance, and Debauchery

Episode 60: Texas and the American Revolution

You might also like:

IHS Talk: “The Civil War Undercommons: Studying Revolution on the Mississippi River” by Andrew Zimmerman

US Survey Course: Civil War (1861-1865)

Harper’s Weekly’s Portrayal of the Civil War: The New Archive (No. 11)