From the editors: This interview was first published in August 2021 by the Toynbee Prize Foundation. Named after Arnold J. Toynbee, the foundation seeks to promote scholarly engagement with global history. The original interview can be accessed here. This interview is published here as part of a new collaboration with the Toynbee Prize Foundation. The collaboration aims to share these important long form interviews with key historians working today.

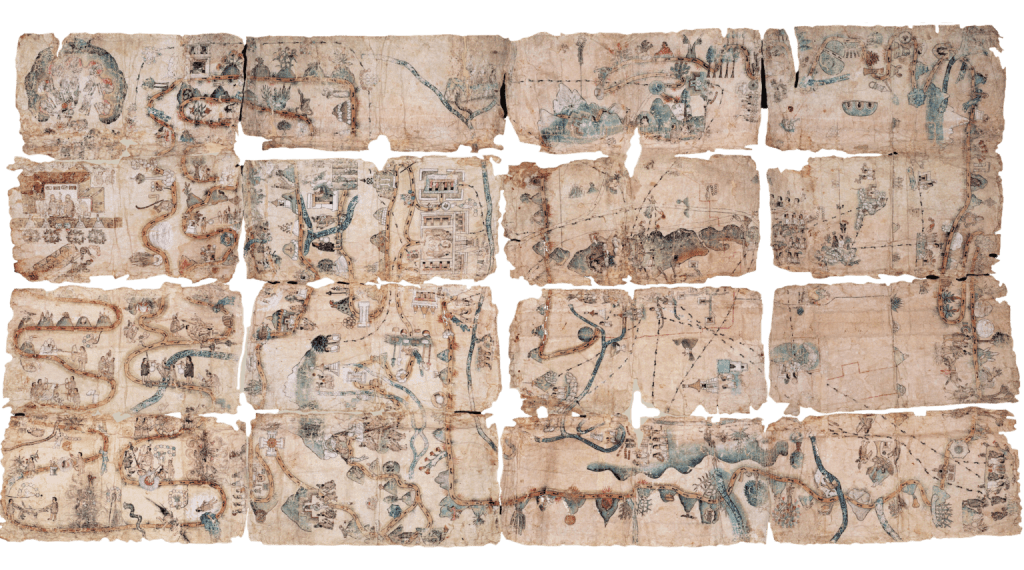

Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra’s work intermingles the colonial histories of the Americas—the United States and Latin America. Cañizares-Esguerra’s expansive historical project is Americanist, yet not in the usual sense of the term. What “America” historically is must engage with a rich contradiction of meaning-making narratives generated by a plurality of social agents. Cañizares-Esguerra resists national containment of such historical narratives and provocatively engages with the early modern and early colonial period (1500s) and with the Enlightenment and nineteenth-century liberalism alike. Themes of belief and faith, of knowledge and science, among a variety of historical agents and subjectivities, feature prominently within his work.

This interview explores Cañizares-Esguerra’s Atlanticism and his cautions regarding certain global history tendencies. Cañizares Esguerra details his current project, Radical Spanish Empire. His aim is to historicize, to radicalize, to Americanize (expansively understood), and to show that colonial Massachusetts is unintelligible without Puebla or Tlaxcala in colonial Mexico, that colonial Virginia makes no sense without its Andean and Peruvian counterparts, and that Calvinists should be understood alongside Franciscans.

Cañizares-Esguerra wants to pluralize the historical narrative outside the conventional liberal moulds of modernity in the Americas. In this, he catches me by surprise when he negates that plural modernities constitute the telos of his enterprise and when he gives the cold shoulder to cultural studies and postcolonial/decolonial studies. The main intellectual thrust of our discussion regarded the intellectual inevitability of native and foreign entanglements, historical and contemporary, and the political desirability that cuts across the “Anglo” and “Latin” divide, at least initially. He offers an expansive Atlantic History, along provocative Iberianizing lines, mixing the “Anglo” and “Latin” categories. It serves as an invitation to go beyond American histories’ extant boundaries, of which there will be many more than two.

—Fernando Gómez Herrero, Birkbeck, University of London

In Adrian Masters and your book about the radical Spanish Empire in the 1500s, you appear to contrast radicalism with immobility, understood as ‘societies of order.’ I am trying to make sense of such “radicalism.” Is it a rich collection of social groups doing all sorts of things that do not fit into neat, rigid, predictable categories?

Exactly. Yes. The 1500s in Spanish America reveals a radical social experiment unique in global history: the creation of a variety of new institutions, categories, new forms of societies that are coming from the factionalism and struggles that are more bottom-up than the top-down. It is radical in that sense of social experimentation that has no predictable outcome. There is no teleology—nobody knew who was going to win. The conquistadors as new feudal lords and their new dynasties might have thought so, but they lost, and they lost badly. And their sons lost badly and they became bastards and mestizos. The Franciscans thought they were winning and they did not win. Neither did the caciques. So, at the end what you have by the 1600s is the merchants as the big winners, but they have to follow the structures peculiar to this ancien régime that is emerging in the New World where paperwork is as important as commodities and capital. To be successful in Spanish America one needed an archive of paperwork, cash, and direct access to lay and ecclesiastical bureaucracies. Race was not necessarily the issue. Anyone with those three things could secure lineages and dynasties for generations.

Could you dive in deeper to show us how that functioned on the ground?

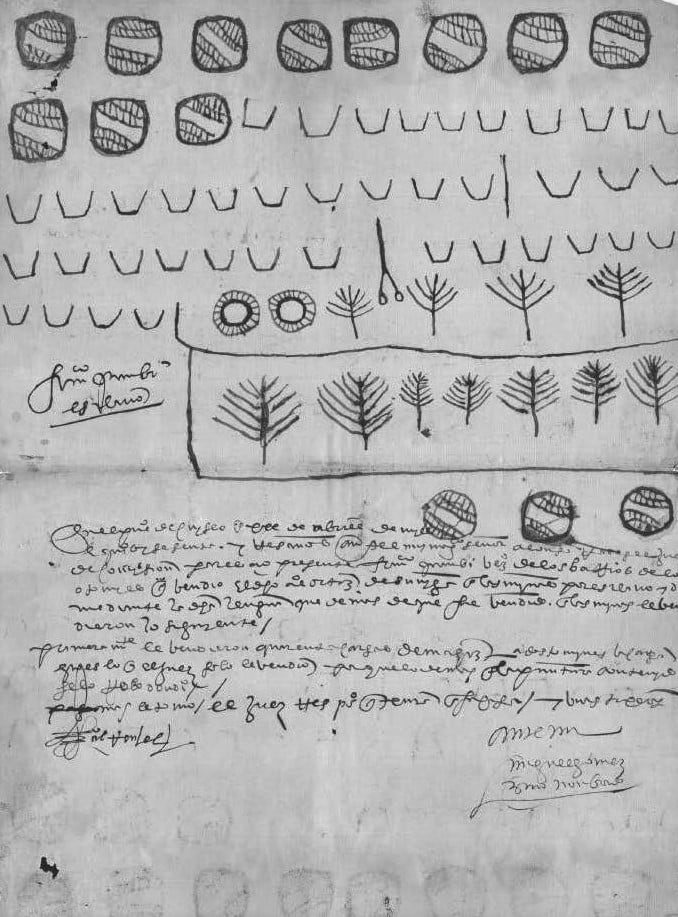

There are three dimensions of imperial administration that are often confused with regard to function: ‘gobierno’ [policy and legislation ]; ‘gracia’ [exemptions and rewards]; and ‘justicia’ [litigation]. The first one, ‘gobierno,’ is about the production of legislation, which our book shows to be bottom-up. This is one of our contributions: understanding that gobierno arises from petitioning individuals, of all kinds and from all quarters, who organize themselves into factions—corporate or individual factions, or sub-factions within corporate ones. After the Comunero rebellion in Spain, the system of councils extends people’s participation in legislation by allowing individuals to write directly to the King and establishing that the King, in turn, must respond through councils to their petitions. Those petitions eventually become cédulas, ordenanzas, and mandamientos. And there are many different layers through which individuals can participate in creating legislation: at the level of cabildos in cities, corregimientos, viceregal units, or at the level of empire as a whole, and it is the responsibility of the authorities to respond to the petitions. Vassals have the right of addressing authorities and obtaining both a hearing and a reply. For example, Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza in Mexico in the 1530s-1550s moved across visitas and hosted hearings in his palace, during which processes he listened to the complaints and requests of indigenous peoples. The Viceroy had to listen to those requests and produce mandamientos, tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands. These were replies to petitions. The same went for cédulas: they were replies to petitions of individuals that through the postal services and procuradores (paralegal representatives or lobbyists) introduced hundreds of thousands of these documents to the King and his Council. Royal cédulas are often verbatim copies of these petitions. So, if you read the cédulas, they indicate “I hereby have been informed by John Doe ” that X is happening, I therefore decree 1, 2, 3, 5 and 5.” And “1,2,3,4,5” are sometimes verbatim copy of the petition of John Doe to the King. So, when you have cédulas, mandamientos or ordenanzas, etc. you have a reflection of all this lobbying and mobilizations of these factions to reform a society through legislation of different kinds, at the local, regional, or imperial levels. And everybody can participate in the crafting of legislation through petitioning. That is “gobierno.”

Gracia is another form of petitioning in which individuals acknowledge the law or the legislation but request exception from it, often on the basis of status: “we are not Indians,” or “we are Spaniards,” or whatever the premise may be. Gracia creates special privileges for individuals vis-à-vis the system, and largely concerns rewards, pensions, and other payments for services provided to the Crown. Verifying that such service was rendered requires witnesses, called probanzas. Initially, conquest was the prototypical service, but it later transformed to service via knowledge production: science, cosmography, etc. Many individuals begin to request gracia around printed books, experimentation in amalgamation in mines or new ovens. As such, there is a history of technology and science within gracia that is extremely rich.

The last element of paperwork is litigation (“justicia”), which is the one that is best known and that legal historians tend to study. This constitutes all the stuff that goes to Audiencias and Council for appeals. It is the costliest process and the one that produces the largest archive. A case can take years and a lot of resources and money, so it is a resource that most people do not have access to and do not use to speak or be heard within government. Yet, outside the litigation of these bulky files of Justicia and Audiencia you can find the participation of the humble, the commoner, the Indian, women, even slaves, in the crafting of the law. In the first eighty years of this process in Spanish America lots of people participated in the creation of institutions. There were no laws; laws were created and arose from the encounters between of all these factions. So, what you began to see were factions and individuals within factions pitted against one another, leading to a lot of mobility, upwards and downwards, and a lot of changes. Suddenly, conquistadors, crate lineages, and dynasties began to crumble and collapse.

Petitioning offers a social history of the emergence of bureaucracies, lay and ecclesiastical, that are pitted against one another, and that are part of different factions seeking to undermine each other. This process engenders a great deal of change in institutions and legislation as well as the creation of archives, but which begins to congeal and slow by the end of the 1580s. We see this process as agentive in the creation of a new ancien régime in the Indies, one that is mercantilist but ultimately predicated on the access to paperwork, to archives. This is because while merchants are the big winners of the whole system, merchants still need to secure the paperwork that will allow them not to be cut to size by rivals. Conversos are merchants who can be easily removed if they do not secure an archive documenting their lineages once the Inquisition arrives in the Indies. So, you have this ancien régime, a system that is very peculiar, new, and unique in global history, I would argue, that is emerging in the Indies out of this dynamic of paperwork that is specific to the New World or the Indies in general. It is also true of the Philippines.

You are a proud historian. As far as I can see you hold most conversations with fellow practitioners in the field of history and less so with those in other disciplines. Tell me something about the profession of history as you see it now. Do you want to remain faithful to the discipline?

Do I see myself as a historian? I see myself as an intellectual more than a historian. I want to have conversations with as many people as possible, not only with historians, but also with scholars and the public in general.

My questions The Radical Spanish Empire are about categories and among them the categories of British liberalism, which are the dominant categories that have informed our interpretations of historical transitions in the early modern period. There are phenomena that we expect to arrive together, stitching our well-crafted understanding of modernity, namely: the printing press, Reformation, public sphere, Enlightenment, Scientific Revolution, democracy. You have that account that is very nicely structured in all Western Civilization textbooks. These categories seem to be assembled in clusters, related to one another and connected with one another, and if you take one, something is missing in these conceptual narratives.

The case of 16th-century Spanish America is telling. It does fit within these narratives of parliamentary democracy. Yet one sees mass political participation from the bottom up without the printing press. These are forms of participation that I would not call democracy, but that nevertheless are from the bottom up, expansive, and wide. They lead to upward social mobility for many groups—commoners, slaves, indigenous—in the Indies that through petitioning manage to recover freedoms, property, etc. Here you also have commoners that challenge the political power of caciques and the creation of indigenous cabildos. This is the manifestation of the rise of commoners against caciques, cacicazgos, formal mayorazgos, indigenous elites detaching themselves from the politics of everyday life in communities that reside now in the hands of commoners, who have to be elected and re-elected into positions of authority. All these changes and mobilities within communities facilitate new understandings of property, of commons, of patrimonial property and realengo. These changes include new definitions what belongs to the state, the family, and the commons. That is all happening in the 1500s in Mexico and Peru. These are major social transformations that are coming from the bottom-up but there are happening through forms of communication that are not driven by the printing press. Social change is not happening through communication via the “public sphere” in the sense that the communication with the King is rather vertical and sometimes secretive in that petitions are often coded. It is a different form of social transformation that is not associated to these aforementioned clusters of categories. And they are not necessarily connected to them.

The clusters of liberal democracy have been so attached to narratives of modernity and democracy that all other forms of transformation that do not follow this teleology or direction are left out and excluded from narratives of transformation or whatever we call modernity—in this case participation, radical social mobility, re-engineering of institutions, and substantive social transformations—prior to the French Revolution.

So, how do you account for that transformation if the categories that you are given pigeonhole those transformations or the experiences of conquest within the category of authoritarian absolutism? We imagine a regime that manufactures categories exclusively from the top-down, creating for example racial categories right, left, and centre, inventing forty different castas? That is absurd! How is it possible for a Queen and her council to invent these forty categories of racial differentiation or castas? It is absurd to assume that there was social engineering happening from Madrid, when in fact it is the social process from the conflict of factions. Factions and rivals created these categories as they fought one another through paperwork, seeking to eliminate rivals from within. The categories of mestizos and the castas were created by Indians or mestizos in order to eliminate rivals around their own communities. It is a different understanding of the origins of these categories that have been attributed to an absolutist regime.

What is to be done (and not done) with the history of Latin America in world history? And in connection to what you just said, what do you want to do to the “liberal” narrative of “modernity” in the Americas?

The liberal narrative of the Americas is very parochial and reflects a very parochial experience of one form of liberal republicanism, one that is British and North European and excludes most other forms of social transformation. What I am trying to do is disconnect these different clusters and show that they can be put together in different ways and one still obtains the major historical transformations out of new combinations. So, you can have major scientific revolutions in Potosí without the printing press and without the public sphere as conventionally understood. You can have it through petitioning, in the three previous modalities of gracia, justicia and gobierno, and you can have it through forms of paperwork, upward social mobility through service, ingenuity, and new technologies that happen in Potosí in a major, massive scale. We are talking about dozens of artificial lakes, thousands of aqueducts that are moving wheels and turbines. There are all sorts of experimentations with chemical combinations in science to speed up the amalgamation process. There is a lot of innovation and experimentation going on about the production of silver in quantities that are so massive that they can transform the global economy. So here you have a technological scientific revolution in the Andes in the 1580s-1600s that is not captured by the categories of Scientific Revolution of the Real Academy of London, or of Isaac Newton or Francis Bacon.

You say you want to “expose the myths underpinning British liberal exceptionalist scholarship,” and to this we must add the United States. So, you wish to pluralize the narrative?

Yes, though not only to pluralize the narrative. The book also offers models of how to pluralize the narrative and how to disjoin these categories from their cluster, a grouping effected by powerful historiographies. These are clusters associated with participation, democracy, etc., that come together and create a narrative of social transformation that leaves everything else out. So, whatever happens in 16th-century Spanish America can leave us only with absolutism, despite the massive evidence of social transformation, upward and downward social mobility, and major political transformations that are happening on the continent. We are left with no categories with which to understand those transformations. Liberalism blinds us to those transformations because it is expecting only certain ways in which social mobility can come about. We are arguing that there are other dynamic ways by which new societies emerge and can transform the global economy that do not necessarily have to be accompanied by the same set cluster of the printing press, public sphere, Enlightenment, etc. You have different forms and combinations. So, this ability to separate modernity from this cluster will allow us to see similar modern transformations, not only in Spanish America, but also in the Ottoman Empire and many other societies. We are offering one way to and see radical transformations free of the dynamics that are part of ancien-regime societies.

You go further because you say that you want to upset the normative narratives operative at the core of such historiographies. You write in the American Historical Review that “the history of the colonization of Virginia and New England reads differently when Iberian America becomes normative,” in your article “Entangled histories: Borderlands Historiographies in New Clothes?” Tell me more. So, not only are you adding a plurality of options, you are aiming to upset and subvert what we might call dominant or mainstream (simplified as “Anglo”) narratives?

That comes from Puritan Conquistadors. But the objective there was to challenge this core narrative of U.S. settler colonialism and the origin of Massachusetts, Chesapeake in Virginia, etc. It is not that they were central to the British Empire. In fact, they were marginal. But they are the core historiographical narratives about the nation in the United States, how the nation comes about. So, colonial Massachusetts plays a central role in that narrative, even though it was a rather or somewhat marginal society in the Atlantic. Same thing for Chesapeake in Virginia. My point in that quote is that those societies are considered to be central to the emergence of American exceptionalism, to what is distinct about the US, the city on the hill, the discourse of Calvinist Massachusetts, etc. And yet these cores to the narrative of exceptionalism are not unlike Mexico in the 1500s. Moreover, they are derivative of those colonial experiences. So, in Puritan Conquistadors, I try to show that many of the things that the Puritans are grappling with when it comes to understanding the New World are questions, concerns, and sensibilities that were first framed and conceived in places like Mexico. So, Puritans are working with these categories that were given to them by the Spanish colonization of the New World, not the other way around. In that sense, I am decentring: there is no history of Massachusetts without Mexico. There is no history of Massachusetts without the Virgin of Guadalupe. There is no history of Massachusetts without Franciscan demonology. There is no history of Massachusetts without Peru.

There is no history of Massachusetts without Mexico or Peru because they knew each other or because the frame of vision has to be wider, more continental-American proper?

Both. For instance, the case of burials. Chris Heaney has written this wonderful article in the William and Mary Quarterly about the burials (“A Peru of their Own: English Grave-Opening and Indian Sovereignty in Early America,” Vol. 73, No. 4, Oct. 2016). When the Spaniards arrive at places, they raided burials and plundered in order to assess the status of the societies they had encountered—whether they were rich, urban, etc. In plundering burials, Spaniards sought to do a quick ethnography and anthropology of places but also to get rich. So, this model of plundering burials was a model that the Puritans themselves applied. And Walter Raleigh too. The British experience in Massachusetts and Virginia saw the same application of burial raiding as a way of quick ethnography and quick returns to capital investments. The conquistador company was not that different from the Virginia company. Puritans and Virginians could not find their Peru and were deeply disappointed as their raids of graves did not yield treasure. The colonization of British America happened through shareholding societies, through contracts with the Crown. This is the model of contracts of, say Cortes, Pizarro, and Almagro. The contracts included certain regions to explore and work to exert authority, taxation, gracia, gobierno, the ability to create legislation, etc. The same happens with the Virginia company. The models were similar, the division of space was similar, the relationship with indigenous people was similar, despite all the rhetoric of difference associated with the Black Legend. There wasn’t much difference.

Serge Gruzinski’s La Pensée Métisse [The Mestizo Mind] is, you write, a book deliberately written to rattle conventions and stereotypes and to challenge the whole industry of “cultural studies” as understood in some circles. Do cultural studies have any traction for you? Do you have any traffic with postcolonial studies?

I think postcolonial studies purposely assumes the same category of the British model of liberal modernity that we are trying to deconstruct. So, from that model, they kind of reverse or invert the vision. They are trapped in the same categories in order to find the process of power and resistance. I have my issues with postcolonialism. It has reified Europe even more than it was. It attributes to Europe institutions that might not be European in origin, but the production of many people. When we say for instance the conquest of the Philippines, or the Spaniards conquered Mexico, we are talking about alliances of a handful of conquistadors with tens of thousands of indigenous peoples. The conquest of the Philippines was led also by Purepechas, Tlaxcalans, Mexicas as much as Spaniards. So, this attribution of modernity and knowledge as “European” leads to a reification of a number of things that in origin are not European. It is kind of giving to these tiny little societies, England, France, Germany, Spain, and Portugal an agency to transform the world. Let’s remember that “Portugal” had only a million people in the 16th century. And whatever happened with Portugal in the 1400s and 1500s, it was not just the creation of Portugal; it was the creation of local alliances in ports all over the world—Ghana, Senegal, Angola, Congo, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Ormuz, Goa, Macao, you name them. So, this is not exclusively Portuguese. This is the creation of local societies just as much as they are Portuguese. In that sense, I am very uncomfortable with postcolonialism’s sweeping reifications of Europe.

There is a superb paragraph in your evaluation of Gruzinski’s work in which you speak of the US as a society “condemned to oscillate between ‘universalist’ and ‘pluralist’ conceptions of the polity, without the tools to understand processes of mongrelisation.” So, there is this universalism of the Anglo-Protestant norm demanding acculturation and assimilation of the “diversity” claims. But you do not seem to be keen on “multiculturalisms” of a “rigid” type or variety. You conclude that “pluralists seem to have won the debate,” but is this still the case in this tense moment of post-Trump, Black Lives Matter and a raging COVID-19 pandemic? What is your political position as it relates to your historical practice?

The problem with multiculturalism is that it takes this idea of minorities as a kind of tossed salad to spice up the main narrative. My point is similar to the fact that African-Americans are claiming a central role in the core narrative of American history; they are not minorities. They are central to the creation of the nation. They are not individuals at the margins. Their numbers may be fewer than those of whites but that does not mean that their agency and their history is in any way a minority history. It is the history of this country. So, multiculturalism has this dimension of reducing the histories of the others as additions to be studied separately in area studies, when in reality these are narratives that are central to the creation of the nation. They cannot be severed or separated. Mexican American history is not Mexican American history; it is the history of the United States. I think area studies tends to do that, to create these niches for minorities to have representation in numbers in universities but within Hispanic or Black spaces. The problem is that things Hispanic and things Black are things American.

The profession of history appears to be operating under a logic of “the bigger the better.” Our units of analysis keep increasing from this or that national history, to continental history, to the Atlantic, to the global, all at a moment of undeniable university crisis with the liquidation of programmes and consolidation of departments. What do you make of these shifts? We are avoiding old-fashioned terminology like “universal history” or “world history” while not doing comparative civilizational histories a la Arnold Toynbee either. What is the nature of this tendency or movement within the discipline?

Yes, there has been this tendency, but it does not mean that we are losing anything in the process. It is not so much the unit of analysis that is changing; it is the nature of the question and the archive, the sources that you draw on. Which means that you can do a very detailed analysis of sixteenth-century Puebla and yet bring to bear a huge global archive to understand what is happening in Tlaxcala, etc. Understanding Tlaxcala, a tiny little altepet [human settlement], requires a global frame and acknowledges that these guys may be connected to the Philippines and China through their participation in the expeditions of[Miguel López de Legazpi. And they have intellectuals like Muñoz Camargo by the 1580s who are commoners acquiring power through the control of the archive as mediators and translators to the Crown and that these individuals are new elites that are replacing the ancien regime. There is the collapse of the old indigenous ancien regime and the collapse of the European ancien regime and the emergence of something new. So, you need this understanding of historical patterns of old societies and new regimes to understand what is new, what emerges in this place that is distinct and novel globally. That is not just Tlaxcala. That is a new social experiment. To appreciate the importance and origin of that you need a global frame.

This question is folksy and playful, but it is meant in all seriousness. Let us imagine an old Brahmin, quite comfortably sipping his brandy in Boston by the River Charles, and after hearing you talking about Tlaxcala this and that, doing some damage to the great liberal narrative of success and power and influence, says to you: “Okay Jorge, fair enough, please remind me why I have to go to Tlaxcala? I don’t care how you frame it or globalize it, it is a small little place, coming from a minor nation that has no importance, so why do I have to go to global Tlaxcala? To find what?”

A good question. To find…

Modalities of being human, I suppose?

To find the cause of the conquest of Mexico, to begin with. To find patterns of colonization and conquest that are reflected in the alliances that Cortés created with the Tlaxcalans. To find patterns of social transformation that are reflected in the emergence of new classes within Tlaxcala that are challenging all lineages and dynasties. To find the role of new indigenous commodities in global markets that are transforming local societies—we are talking about the cochineal dye, exported from the Tlaxcala and the Mixteca or Oaxaca areas. So, you can find a number of things that are relevant to many global processes that are affected by or affect anyone and everyone. Without Tlaxcala there is no Acapulco and there is no expedition to the South Sea and no full understanding of Legazpi in the Philippines.

You write something that I find very provocative: “it would seem that what scholars of early modern Catholicism have called baroque, scholars of Calvinism have called typology.” Tell me more about this.

In Puritan Conquistadors I make the argument that Puritanism and Calvinism were greatly informed by the Old Testament, and their understanding of their mission in the New World was informed by the reading of prophets and the Book of Exodus and Numbers and Genesis, etc. That Calvinism is a hermeneutical project of reading the New Testament in light of the Old Testament. That is a Medieval tradition that is called typology. And that yields prophecy as well. This is also what the baroque is about.

I do not think the Anglo world engages with the baroque in a way that assumes and absorbs it as something that is of its own. The baroque is always this outside, that is colourful, that is not knowledge; it is eccentric, it is what others do. The tough question will be, how to vindicate the baroque, not in a sentimental, imperialist fashion, but how to engage with that in a way that at least holds up the mirror to different enclaves. It is not easy at all. Shakespeare is not baroque, for example, and he is perfectly contemporary with the eminent Spanish baroque playwright Pedro Calderón de la Barca. They are kept completely separate at the categorical level. Same thing with John Donne’s poetry and Francisco de Quevedo’s and Luis Góngora’s. You put the texts side by side and they are clearly in the same universe, but not according to conventional historiographies. There is an Anglo repudiation of a category that is not nativized. It is o.k. for Bernini in Rome, but it is not for St. Paul’s in London. Your provocation is thus to put baroque, Catholicism, and Calvinism together and to try to work one’s way through.

Right. The baroque sermons are essentially a Calvinist text in a form of “jazz” in which the priest of the female prophet is given a text from the Old Testament, with echoes in the New Testament. They worked their way through this text to try to understand what they prefigure for events today. So, it is an understanding of the present through the prism of prefiguration and fulfilment. In the same way that Calvinism does it, which is also typological. Puritans saw themselves as Israelites in promised land; they saw the natives as Cannanites. The whole idea of the promised land in New England is a constant reading of their experience through the prism of the Old Testament. So, they are writing mosaic constitutions right and left in Massachusetts. I do not see much of a difference between these two hemispheric sensibilities, not even rhetorically—the Mexican one is as symbolic and as twisted as the Puritan other. This is what I meant by baroque and typology.

Is the notion of “multiple modernities” the telos of your historical work?

No. The telos of my historical work is politics and power. It is about undermining narratives of modernity that take away power from groups and communities at least in the United States and Europe that have as much claim over those societies as anybody else.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.