From the editors: This article first appeared in QT Voices, which is the online magazine of the LGBTQ Studies Program at The University of Texas at Austin. For the original article see here.

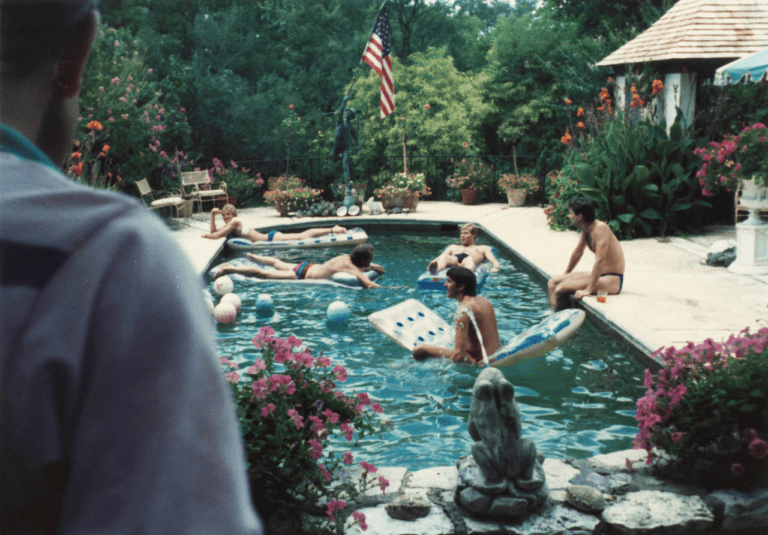

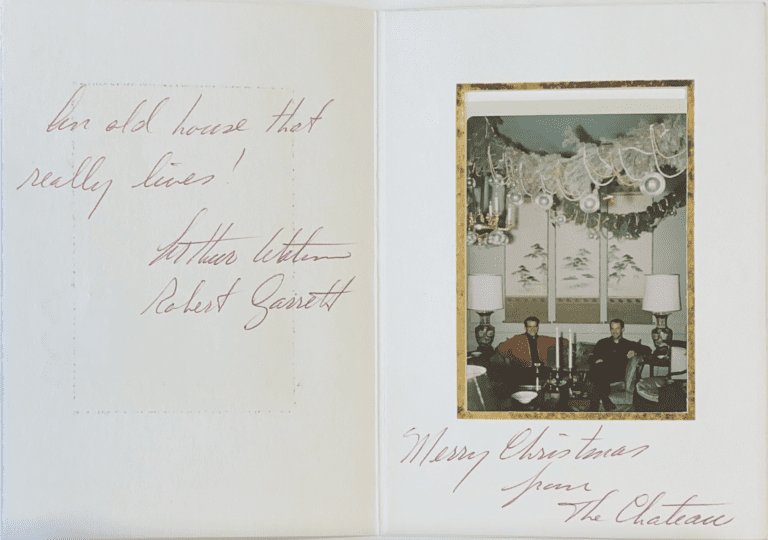

“If at all possible and, if my voice is loud enough, your house will be spared by the bulldozer.” This was the encouraging message received in the summer of 1965 by Arthur Pope Watson, Jr. Watson, a well-connected Austin designer, shared the home located on the edge of the UT campus with his partner, Robert Wayne Garrett. Watson and Garrett worked together and owned an interior design firm, Watson Associates, for over three decades. The note came from Coke H. Dilworth, an architect at the local Brooks, Barr, Graeber, and White firm. Dilworth had just toured Watson’s historic home at 500 East Eighteenth Street and was impressed by its grandeur. Adorned with a French-style mansard roof, lush gardens and grounds overlooking Waller Creek, and opulent interior design hand-curated by Watson and Garrett, the home—nicknamed “the Chateau”—was a breathtaking structure with a fascinating history. The Chateau famously hosted formal dinner parties, cocktail soirees, and holiday fêtes—gatherings that Garrett laughingly described as “very elegant, but . . . rowdy.” It has been reported that celebrities even visited the Chateau for parties or after performances at the Erwin Events Center, and rumored visitors include actor Rock Hudson and tenor Luciano Pavarotti.

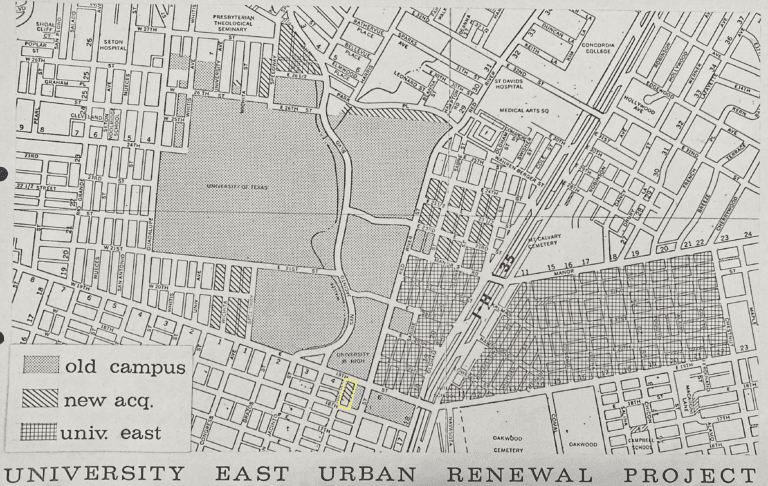

The bulldozer in question was to be sent by the University of Texas at Austin, which was in the middle of seismic changes in the 1960s: student enrollment was growing exponentially, and the University was struggling to keep up with demand. The Board of Regents’ solution was to undertake a massive campus expansion to the east, northeast, and southeast existing edges of campus, and the Chateau was directly in the path of this expansion.

The University’s expansion plan was authorized by House Bill 492, which was initially introduced in March of 1965 and quickly gained Senate approval, passing in April. The bill gave the University the legal right to acquire over twenty blocks of property surrounding the campus under the power of eminent domain. When the bill was first introduced to the Senate, only four citizens appeared to express their disapproval; Watson was one of them, alongside other landowners in the path of expansion. These dissenters argued that the University had not specified a clear or immediate purpose for the acquired land and that it would likely remain undeveloped for years. U.T. Regent W. W. Heath, on the other hand, argued in favor of the bill, reporting that one of the University’s predominant concerns was that a “delay in acquiring the land would mean the land would have to be bought later at a higher price.” Meanwhile, the bill’s framer, Senator Charles Herring, said that “the University ha[d] a moral obligation to buy the land as soon as possible from those who wanted to sell.”

Senator Herring’s rhetoric suggested a choice—that the University would buy property “from those who wanted to sell”—but eminent domain is ultimately disinterested in the desires of landowners. More commonly, eminent domain is used to override those desires explicitly and, in June of 1965, the University did just that. Watson received a letter from James Colvin, Business Manager of the University, informing him that U.T. formally intended to acquire his land at 500 East 18th Street. Like Herring, Colvin closed his letter alluding to a semblance of choice, telling Watson, “if you wish to retain your property for as long a period of time as is consistent with the needs of the University, or for some fixed period of time, please advise me of that fact and we shall accommodate you insofar as it is possible for us to do so.”

Watson indeed wished to retain the Chateau. Built in 1853, it was one of the oldest buildings in Austin, and was constructed with historic materials: the original structure was fashioned from hand-cut stone that came from the same Austin quarry as the original Capitol building, which burnt down in 1881. Caroline Roget, the Chateau’s previous owner and Watson’s and Garrett’s personal friend, had added numerous features to the home after purchasing it in 1945. According to a 1997 interview with Garrett after Watson’s death, Roget, who was Governor Beauford Jester’s assistant, installed lights and sconces at the Chateau that she had taken from storage buildings at the Capitol, including an outdoor light salvaged from the 1881 Capitol fire. She also hired local artisans Weigl Iron Works to do ironwork on the interior and exterior of the home. When Watson and Garrett purchased the home from Roget in 1959, they enclosed the home’s balconies in glass, built two new garages, constructed the English-style greenhouse, and installed a pool blasted out of solid limestone.

Watson was not ready to part with the Chateau and all that it meant to Austin society—particularly, Austin gay society, which often gathered there during these parties. He responded to Colvin’s letter saying that he wished to “retain the property for as long as possible,” citing its historic significance to early Texas architecture. As he notes, the Heritage Society of Austin had recently included the Chateau on a Pilgrimage of Historic Homes tour.

Though the University’s official notice did not arrive until 1965, mentions of the University potentially acquiring the property can be found in records before then. In Board of Regents meeting minutes from October 1964, campus architects propose numerous parcels of land the University should attempt to acquire, and the Chateau is included within their recommendations. The plan speaks of the Chateau in quite impersonal terms, describing simply that the lot had one house, whose “price may be prohibitive.” In place of this rich historical site, the architects had grand plans: an overflow storage facility, or perhaps a parking lot.

Watson seemed to also have an intuition before receiving the University’s official word. In a letter he sent Roget in May of 1963 about potentially adding another structure on the plot, he mentions that “the area has come into recognition at City Hall… it isn’t possible to have a vacant lot in the center of town [anymore].” Later in their correspondence, as he describes a number of structural issues afflicting the Chateau and laments the expense of their repair, he asks rhetorically, “who can find cash these days when the government wants everything?”

Two years later, the government did want everything, and intended to take it by brute legislative force. Land appraisers and real estate brokers moved in on all sides of the Chateau. Individual landowners of nearby tracts sold their homes to the University, while entire communities were displaced eastward. By 1968, the plan for the land acquired by eminent domain would be shaped into the University East Urban Renewal Project. According to environmental historian Katherine Leah Pace, “the [Project] displaced an interracial neighborhood located just east of the UT campus” and “‘removed the remaining Black families from along the west side of IH-35.’” The University was aggressively invested in making progress on its campus expansion projects; as a March 1965 article in the Daily Texan gravely predicted, “progress, however, demands the past be destroyed.”

Despite Watson’s written protestations, in September 1965, Colvin sent him another letter reiterating the University’s intent to acquire his land and informing him that independent real estate appraisers would soon be visiting the property to determine its “fair market value.” Colvin attempted to assuage Watson, saying “we have noted your request that we delay the acquisition of your property as long as possible.” Just two months later, though, Colvin again wrote to Watson, informing him that realtors would soon visit him to “negotiate the purchase” of his property. Dilworth’s reassurance that the Chateau may “be spared by the bulldozer” seemed less and less likely with each passing day.

Watson had one last lifeline to try, and it was one that would ultimately prove successful in sparing the Chateau the bulldozer—though not without contractual stipulations. When Watson was an undergraduate at U.T. in the 1940s, he crossed paths with then-Law School student Frank Erwin at their fraternity house, Kappa Sigma Tau, and they struck up a friendship. Little did they know that nearly two decades later—and in the middle of the University’s vigorous expansion—Watson’s old friend and now powerful local attorney Erwin would be sitting on the U.T.’s Board of Regents, wielding partial control over the future of the geography of campus and its surrounding areas.

Garrett described that Erwin and Watson were “great buddies” who “got along extremely well together, under any circumstances.” Garrett called Erwin a “wonderful guy,… almost like family,” who would come over to the Chateau to visit Watson and Garrett “all the time, late at night—after he’d been down to the Quorum Club. [A local bar known to host politicians and other powerful local figures.] If he happened to have a problem… he’d just—eleven o’clock—he’d bang on the front door.” He pointed to Erwin’s great friendship as he and Watson “went through a seven-year battle to save” the Chateau, saying,

I didn’t have much control over it. I was living here, but I didn’t know what Arthur and Frank were up to most of the time. Then finally Frank came to the rescue, and they drew up this agreement, and so it went to the University and that was fine—and so that was how it saved the house-—by Arthur giving it to the University-—with a lifetime [agreement]-—he could live here as long as he was alive. [Erwin] told Arthur—he says—’Well, I’m going to go take this and bury it in the files. […] So we never heard from them again—the University—during all those years. We didn’t have to ask permission to do anything.

As Marta Stefaniuk, primary researcher of the To Liberate: Watson Chateau project, points out: “the paper trail tells the public facts on which everyone can agree. There were also backroom deals, never made public, but still clear in the memories of the few remaining Austin residents connected to the arrangements.” What the public record does show is that Watson was first made aware of the University’s intent to acquire the Chateau in 1965 and, in September of 1973, he officially gifted the property to the University in exchange for “a life estate in the premises.”

The details in the intervening years are few and far between. There is an intriguing moment on public record in February 1966, when Erwin sounded the alarm at a U.T. Regents meeting. The Regents were discussing the City of Austin’s plan to expand Red River Street, which Erwin called potentially “disastrous” to the structures on the east and west sides of the street (one of which was the Chateau, though Erwin did not name it specifically). While he expressed these concerns, all other Regents, including Chairman W. W. Heath, approved the expansion. Of course, there is no way to know whether or not Erwin was campaigning on behalf of his friend Watson’s property, but it is interesting to consider he was the only Regent to raise an issue about this plan, particularly when Erwin was quite supportive of—even aggressive about—expansion otherwise.

In 1969, Erwin was directly involved in a series of protests against University expansion that have collectively become known as “the Battle of Waller Creek.” As the University continued its eastward growth, it planned to re-route a section of Waller Creek to allow for renovations on Memorial Stadium and the construction of Belmont Hall. In order to do that, the construction team was directed to remove thirty-nine live oak trees, many of which were over 100 years old. A committed cadre of students, horrified by the news of the planned tree removal and brimming with activist energy amid anti-Vietnam War protests, climbed the trees of Waller Creek and promised to stay there until the plan to remove the trees was scrapped.

Regent Erwin—a polarizing figure, especially during his tenure as Chairman of the Board from 1966 until 1971—took matters into his own hands. Erwin directed campus and city police to get up on ladders and remove the protestors forcibly. According to witness accounts, some branches were cut with students still in them, and twenty-seven students had been arrested by day’s end. “‘Arrest all the people you have to,’ the chairman told one officer. ‘Once these trees are down they won’t have anything to protest.’”

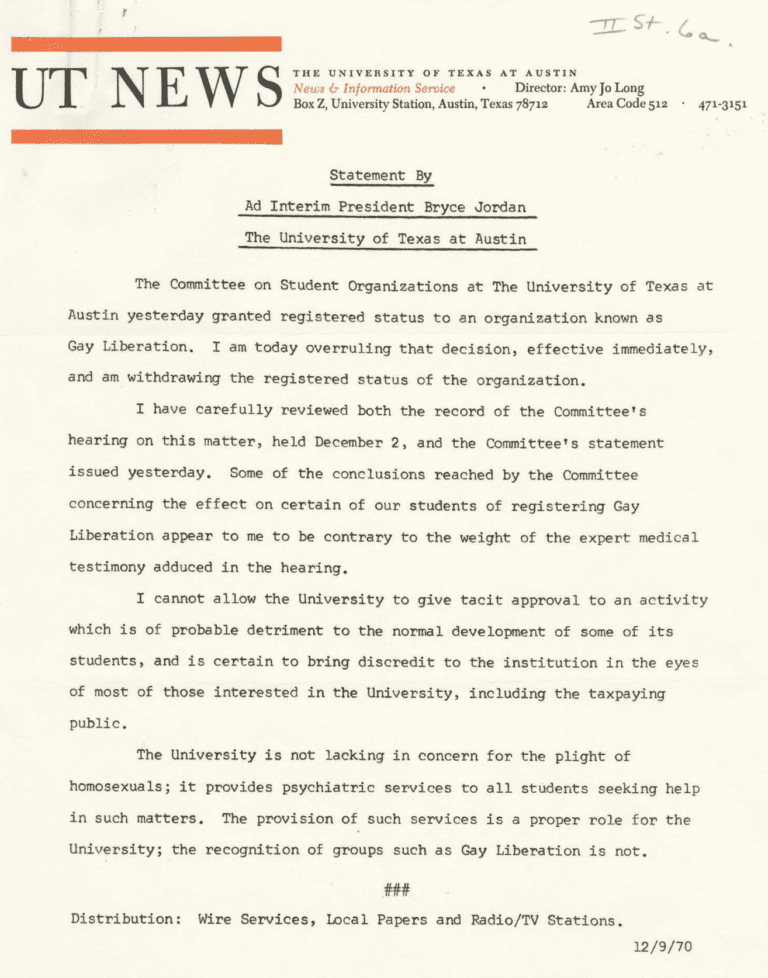

This was not the only time Erwin came to metaphoric blows with student protestors in his tenure as a Regent. In 1970 and in the wake of the watershed Stonewall riots in New York City, gay students at U.T. got together to form the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and applied for official campus group status—which they were denied. In a statement about his decision, Ad Interim President Bryce Jordan wrote that the University was unwilling to “give tacit approval to an activity which is of probable detriment to the normal development of some of its students, and is certain to bring discredit to the institution in the eyes of most of those interested in the University, including the taxpaying public.”

Dissatisfied with the administration’s decision and invigorated by lesbian and gay activism sweeping the country, the student group sued the University and was represented by Students’ Attorney Jim Boyle in their suit. Shortly after the case was announced, Chairman Erwin introduced an emergency item to the Board to change the rules determining who the Students’ Attorney (technically, a University employee) could or could not represent. This new legislation, passed quickly by the Regents, disallowed the Students’ Attorney from advocating on behalf of students when filing a case against the University. Erwin admitted the “rule was passed specifically because of Boyle’s representation of Gay Liberation.” Regent Joe Kilgore expressed the Regents’ sentiments even more plainly: “Well, Boyle put himself in a precarious position by defending homosexuals.”

While Erwin and other Regents went toe-to-toe with “homosexuals” demanding basic institutional recognition on campus, the friendship between fraternity buddies Erwin and Watson, and Watson’s partner Garrett, remained strong, built on rock-solid racial and class privilege. Erwin was a frequent attendee of the Chateau’s lavish dinner parties and helped facilitate a robust working relationship between the University and Watson Associates interior design firm. During the 1960s and ‘70s, U.T. hired the firm to decorate the renovated Chancellor’s Bauer House, the Littlefield Home, the U.T. Systems building downtown, and the campus Regents’ Room, and Erwin hired them to design his personal home at 2307 Woodlawn Boulevard. It seems likely that Watson Associates’ relationship with the University and Regent Erwin had an impact on U.T.’s ultimate decision to extend Watson and Garrett lifetime tenancy at the Chateau.

Meanwhile, and despite the Regents’ best efforts to quell queer activism, the on-campus movement grew during the ‘70s and beyond. Queer student activists helped coordinate the first GLF conference in the 1970s, organized campus awareness weeks in the 1980s, and fought for a non-discrimination policy that would protect sexual orientation in the 1990s. As queer organizing flourished, Watson and Garrett continued to host their grand parties at the Chateau, eventually moving the offices of Watson Associates to the home’s sunroom and two garages, until Watson passed away in January 1993. As Garrett detailed, the University faxed over a new agreement nearly immediately after Watson’s death, offering him a ten-year lease to remain at the Chateau. The lifetime agreement the University had made in 1973 was apparently with Watson specifically and only, as the official property owner. This was a surprise to Garrett, who said he thought the lifetime lease extended to him, as well. While this new agreement made his future at the home precarious, he was ultimately able to extend the agreement and continued living there until 2009, when he moved into a condo in North Austin. He lived there until his recent death in November 2021.

The Chateau is a critical monument to the mixed legacies of Austin’s LGBTQ+ history, and one that is currently at grave risk of being lost forever. The fact that a gay couple weathered University expansion in the 1960s is miraculous. The fact that the house still stands today—though in worsening disrepair, its future unclear—should be celebrated. That said, the history of the University’s acquisition of the Chateau, paired with the history of other campus events that occurred simultaneously, offers some important insights into the advantages of racial and class privilege and what those could afford queer people in this period. As described earlier, University expansion displaced an entire neighborhood of Black homeowners, a move that, along with the 1928 City Plan, forever shifted the racial geography of Austin. Furthermore, the protections that class privilege allowed Watson, who came from a wealthy, high-society Austin family, were clearly not offered equally to all gay and lesbian community members at the time, as the University continually attempted to suppress radical on-campus activism.

Today, community members continue to agitate for the preservation of the home—it is, after all, a critical nexus of many of Austin’s histories: racial displacement, campus activism, University expansion, and gay society. These community members demand that the University invest in renovating the Chateau to its former glory, or at least more fully document and remember its historic legacy. They hope that ultimately, despite the Daily Texan’s predictions in 1965, progress does not demand the past be destroyed.

Author’s Note: this article owes much to the intensive research undertaken by Marta Stefaniuk, primary investigator for the Oakwood Cemetery Chapel’s To Liberate: Watson Chateau project on the historic home. I encourage readers to explore Stefaniuk’s project for a more in-depth look at the Chateau’s long and rich history. This article intends to offer supplemental contextualization about campus expansion and U.T.’s acquisition of the Chateau, bolstered by timelines constructed by Stefaniuk.

Hartlyn Haynes is a Ph.D. student in the Department of American Studies and a graduate research assistant at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. She serves as a research assistant to Dr. Lauren Gutterman studying UT’s LGBTQ+ history as part of the Campus Contextualization and Commemoration Initiative, which aims to create public history and commemorative projects that shed light on marginalized histories across campus. Her academic research focuses on the intersections of political economy and memory politics in HIV/AIDS memorials in the United States.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.