This is an important revisionist work. In Resurrecting the Granary of Rome, Diana K. Davis makes a compelling argument that existing evidence and recent research in arid land ecology do not support many of the claims regarding deforestation, overgrazing, and desertification in North Africa. This argument challenges the French environmental narratives of North Africa, which aided them in the colonization of the Maghreb (Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia). Davis discusses how the French colonial regime used environmental narratives to enable them to exploit the Maghreb from the 1830s to the end of colonial rule in French North Africa.

Divided into three chapters, Davis’ book begins by providing a historiographical context for the work. The book begins by exploring the existing literature on the environmental history of North Africa while locating a lacuna that provides the focus of the work. She argues that the French environmental narrative of North Africa was episodic; it only captures the environmental decline of the Maghreb after the Arab invasion in the eleventh century. However, deforestation and desertification predate the invasion of the Arabs. Research indicates that these processes occurred for millennia in North Africa. Hence the need to put the environmental narratives in a more appropriate context, acknowledging both indigenous (colonized) and foreign (colonizer) agencies.

Davis discusses the differences between the ways precolonial and postcolonial North African narratives describe agricultural fertility. During the pre-colonial period, the natural environment was pictured as pristine, not degraded, deforested, or ruined. Precolonial narratives about the environment also presented the local population as passive and thus unable to exploit the potential of the land. By contrast, colonial narratives presented the “Arab invasion” of North Africa in the eleventh century as a singular force in the degradation of the environment. Together with other factors such as trade and politics, French colonial narratives became instrumental in the colonization of the Maghreb starting from Algeria between 1830 and 1848.

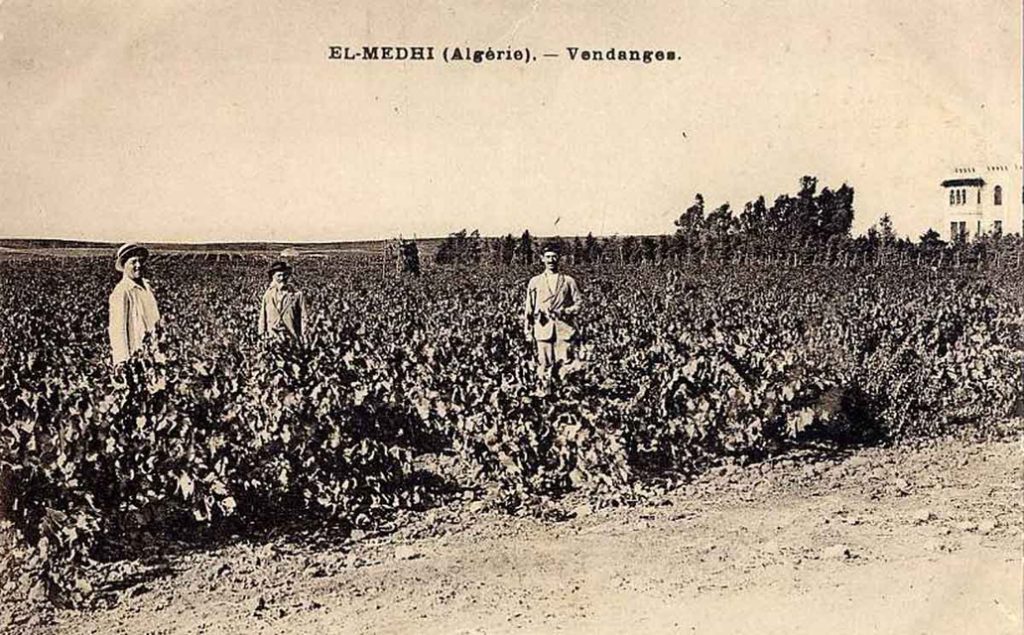

After exploring the colonization of the Maghreb, Davis examines how French narratives were vital to the administration of colonies in North Africa. The narratives encouraged and expanded the French occupation of Algeria as indigenous populations were removed from their best lands to make way for colonial agriculture. The period witnessed the establishment of forestry serves to deal with deforestation and desertification in Algeria. Two environmental theories emerged: the theory of deforestation and the theory of desiccation. According to Davis, the latter informed much of Algeria’s forestry policies during the colonial and postcolonial periods, as the French believed that planting trees would attract and increase rainfall.

Davis explores the patterns of change in narratives about environmental decline between 1870 to independence. The pattern of change in the narratives served three purposes. The declension narratives were key in the appropriation of land and resources. French colonizers premised their occupation of the Maghreb on the need to avoid further deterioration of the environment. Also, the narrative served as a means of social control, also controlling the provision of labor. The French narratives created conservatory laws to protect the environment. These laws restrained the local populations from Indigenous agricultural practices such as bush following and shifting cultivation. Lastly, declensionist narratives led to the transformation of subsistence farming into commodity production. This sought to make lands more profitable.

Through its analysis of the Maghreb, this book makes a valuable methodological and analytical contribution to the study of the North African environment. Davis drew upon extensive primary documents in Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, and France, which she skillfully blended with other secondary sources. The sources are woven into six chapters with a brief but insightful conclusion. However, the book has some limitations. The book is largely silent on the resistance of indigenous Algerians to French occupation. Under the leadership of Abdul Kadir, most of the fertile lands were held by the resistant groups. By 1839, he controlled more than two-thirds of Algeria, having most of the fertile lands. It was after his capture that the French had control of Algeria. It is interesting to note that Abdul Kadir’s name is not featured in the entire narrative on land occupation in Algeria. Kadir’s green (which stands for the field) and white standard was adopted by the Algerian liberation movement during the War of Independence and became the national flag of independent Algeria. A further description of the resistance group, led by Kadir, would have given more agency to indigenous Algerians in the narrative. However, these are minor reservations in a refreshingly creative and revisionist work.

Resurrecting the Granary of Rome significantly contributes to the growing body of environmental history in North Africa and Africa. It points to new avenues of research on the relationship between colonialism, environmental narratives, and history in Africa. Focusing on Maghreb’s environmental history, Davis addresses the mistaken notion that the indigenous people of North Africa are to be blamed for the degradation of the environment. The book forcefully compels its readers to reject French colonial declensionist environmental narratives and instead support the environmental story of the nomads who have been largely misperceived and misread over the years.

Victor Angbah is a doctoral student in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. His research interests include education, agriculture, and riverine histories of Africa. He is currently researching the symbiotic relationship between the Pra River and the Akan people of Ghana, West Africa, in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.