Look at any firehouse in Austin and you will see a yellow sign on the exterior marked “Safe Baby Site.” These signs date from 1999 when a rash of discoveries of dead newborns in and around Houston, led Texas to pass a “safe haven” law. Anyone who abandoned a baby younger than sixty days at a designated “safe” spot, where the newborn would quickly be found and receive appropriate care, was promised amnesty from prosecution. All 50 states subsequently passed similar laws.

The practice of child abandonment and efforts to manage it have a long history and I recently encountered a series of surviving artifacts from about 250 years ago that provide us with a rare window into the abandoned and the abandoners. In France, as in other European countries, the frequency of abandonment led to the development of institutional responses to protect the children with the establishment of foundling hospitals in towns and cities across Europe. Contrary to what we might expect from modern laws which envisage child abandonment as a crisis response by a teenage single mother with a newborn, children were abandoned in early modern Europe at all ages by parents who were married and by various extended kin as well as by young single mothers.

Reminders of these municipal refuges survive today in the landscape of modern cities, like Coram’s Fields in London’s Bloomsbury neighborhood, site of the original London Foundling Hospital and today home to a wonderful playground interlude for any travelling family as well as for local children.

Reminders of these municipal refuges survive today in the landscape of modern cities, like Coram’s Fields in London’s Bloomsbury neighborhood, site of the original London Foundling Hospital and today home to a wonderful playground interlude for any travelling family as well as for local children.

In the archives of the city of Lyon, home of one of France’s largest foundling hospitals from the mid-sixteenth century, records survive for each child admitted, often with a record of the circumstances of the abandonment (where, at what time, and a careful description of what the child was wearing) as well as any note left with the child. Many notes were written on scraps of paper apparently just torn from whatever might be to hand, others were written on playing cards, a few on saints cards. Some parents were smooth writers and some had barely functional literacy. They were written by fathers and by mothers.

Each one of these scribbled notes tells a capsule story that offers us a tangible connection with a long ago moment of family crisis. They briefly allow us to see the decision to abandon a child from the parents’ perspective. These are decisions working people faced with economic desperation and religious sensibility.

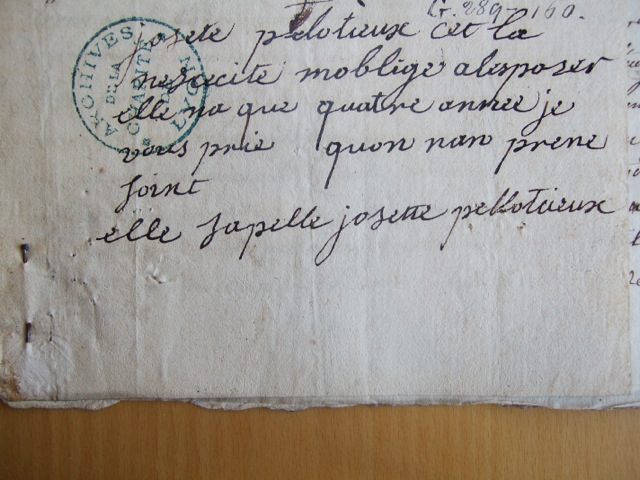

About 10 pm one evening, a cook found a young child of about 4 in the square in front of the city’s cathedral. She was wearing two skirts, a shirt and coverlet and black shoes. The cook found a note “on the child” that said under a small hand drawn cross, “Josette Pellotieux It’s necessity that makes me expose her She is only four I beg you to have someone take care of her She is called Josette Pellotieux.” The cook duly took Josette to the foundling hospital where the admissions clerk recorded that the note “appeared to have been written in a woman’s hand.” Josette’s mother was probably a textile worker, the most common job for women in Lyons where textile manufacturing dominated the economy. She was probably a widow, like many women who abandoned their children, unable to make ends meet without the income of two adults.

About 10 pm one evening, a cook found a young child of about 4 in the square in front of the city’s cathedral. She was wearing two skirts, a shirt and coverlet and black shoes. The cook found a note “on the child” that said under a small hand drawn cross, “Josette Pellotieux It’s necessity that makes me expose her She is only four I beg you to have someone take care of her She is called Josette Pellotieux.” The cook duly took Josette to the foundling hospital where the admissions clerk recorded that the note “appeared to have been written in a woman’s hand.” Josette’s mother was probably a textile worker, the most common job for women in Lyons where textile manufacturing dominated the economy. She was probably a widow, like many women who abandoned their children, unable to make ends meet without the income of two adults.

What did the future hold for Josette? She may have stayed in the hospital until she was 16, before being placed as a servant like many children. Perhaps she died there as mortality rates were exceptionally high in these institutions. She may have been retrieved by her mother later when resources allowed. One widow, Jeanne Gachet, abandoned two children in 1757 after the death of her husband, a shoemaker, at a time when she was so ill that she was unable to work as a silk spinner and feared she would die.. She retrieved Pierre first in 1760 and Genevieve two years later, promising in each instance to raise them as good Catholics, teach them to read and write, and to raise them so that they could earn a living. A shoemaker-cousin, a family friend, and a textile producer who Jeanne had been working for at the time of the babies’ abandonment attended the return of Genevieve to her mother.

Some parents wrote their notes on playing cards and we can wonder whether they were making specific statements in such choices. Did parents mean to indicate they were gambling that their child would be better off in the care of an institution than in their care?

Some parents wrote their notes on playing cards and we can wonder whether they were making specific statements in such choices. Did parents mean to indicate they were gambling that their child would be better off in the care of an institution than in their care?

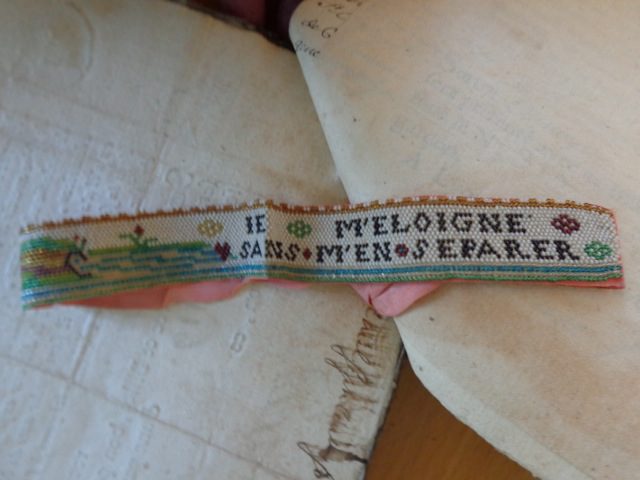

The most telling and touching of all of these artifacts for me is a pink ribbon attached carefully to a baby’s wrist and embroidered with the message: “I am going away but remain close.” Likely embroidered by the baby’s mother with the fine skills of Lyonnais textile workers, this tiny memento gives us a material connection to a world of terrible choices and elided emotions.

Photo Credits:

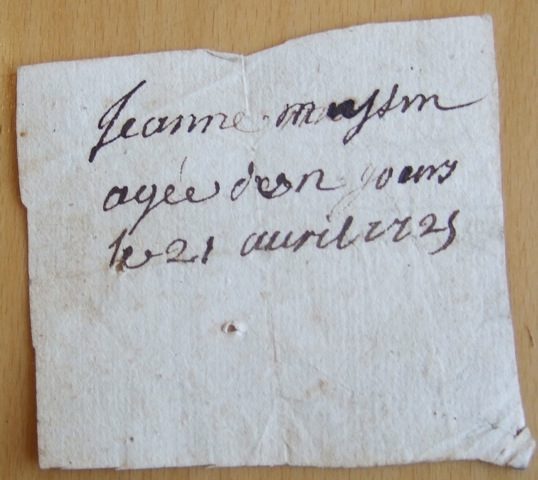

A note written for Jeanne Masson, aged one day, 21 April 1725 (Image courtesy of Archives Municipales de Lyon HCL Charité G288)

The note found on Josette Pellotieux by a Lyon cook (Image courtesy of Archives Municipales de Lyon HCL Charité G288)

An embroidered pink ribbon bearing the phrase, “I am going away but remain close.” (Image courtesy of HCL Hotel-Dieu G85)

***

You may also like:

Julie Hardwick examines the daily life of Early Modern French families