Arthur Koestler lived a remarkable life – as dramatic a death-defying tour of twentieth century Europe as you can find. He was born in Budapest (in 1905) and went to school in Vienna. As a young man, he took up any number of political causes, beginning with socialism and Zionism. He went to Palestine as a reporter, but found it too remote, so he repaired to Paris and in 1930 went from there to Berlin — just as the Nazis were making their electoral breakthrough. He became a communist and went as a journalist to visit the Soviet Union. (Langston Hughes visited at the same time; the two men met in Turkestan.) By 1933, the Nazis had taken over Germany, and a Jewish Communist could not return there, so Koestler resumed his writing and political activity in Paris. He was next dispatched to report (and spy) in the Spanish Civil War, working for the Loyalists. (The Loyalists tried to defend the Spanish Republic against General Francisco Franco’s Nationalists and their allies in Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The war, which in ended in 1939 with Franco’s victory, is sometimes called a “dress rehearsal for World War II.”) Koestler was captured by Nationalists in 1937, locked in solitary confinement, and told he would be executed. In Darkness at Noon (his most famous book, a novel about the Soviet terror of the 1930s), the chilling scenes of men being dragged from their cells in the middle of the night to be shot by Stalin’s police are based on Koestler’s own experience of imprisonment in Seville. An international campaign of journalists, the League of Nations, the Red Cross, and others got Koestler released to the British. For the next three years he tacked between France and Britain, writing first Spanish Testament, then Darkness at Noon before being arrested by the French in the fall of 1939. After escaping that ordeal, he worked for the British Ministry of Information, reported on the war and recounted more of his own experiences in Scum of the Earth and Dialogue with Death.

By the late 1940s he was an intellectual celebrity, best known as a disillusioned former Communist with anti-fascist credentials. Koestler also wrote about science, however, flirted with parapsychology, and pursued women, by all accounts treating them very badly. He and his younger, third wife committed suicide together in 1983, about five years after he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. All of this is well chronicled by Michael Scammell in Koestler: The Literary and Political Odyssey of a Twentieth-Century Skeptic but Koestler tells the political part of his own story with more verve than any biographer.

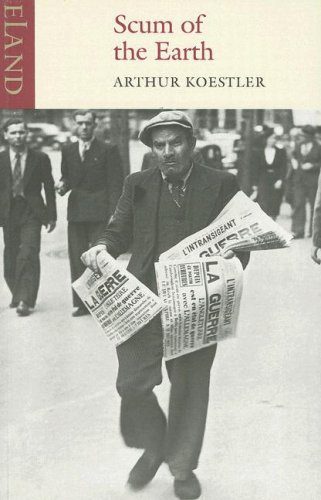

Scum of the Earth (1941) is the best volume of Koestler’s memoirs – not as well known as Darkness at Noon, but almost as frightening, and not fiction. It begins in August of 1939, in the surreal and depressing quiet on the eve of World War II. Since it is August in Europe, Koestler is the south of France, eating bouillabaisse in St. Tropez. The war would not come to France itself until May of 1940, but even before that, the French Republic began to round up “undesirable” foreigners. One might expect an anti-fascist intellectual who had been condemned to death for fighting in Spain to find asylum in France, which was after all the land of the revolution of 1789, the longest standing republic in Europe, officially anti-Nazi and preparing to fight Hitler. Koestler certainly hoped he could count on the French state’s protection. So did thousands of other political refugees from Nazi Germany and its affiliates, like Hannah Arendt. But he was arrested, held outside of Paris (at the Roland Garros stadium) and then shipped to a remote interment camp, Le Vernet, in the Ariège, near the Spanish border. He managed to escape at the end of the year, and then chronicled the fall of France (“a country which has reached the bottom of humiliation”) and his and others’ desperate search for visas or permits to get off the continent.

Scum of the Earth takes us through Koestler’s fears of being arrested at any moment and his bewilderment in face of the implacable French police. It gives us an excellent feel for France during the war – the more remarkable because it takes place before the collaborationist Vichy government was set up. Koestler offers moving portraits of some of his fellow prisoners: a Jewish socialist refugee from Czechoslovakia; an Italian who had spent nine years in prison and been tortured by Mussolini; two fellow fighters from the Spanish Civil War; and a Polish Jew who had fled the pogroms and worked as a tailor in Paris for decades. “What nearly all of them had in common was being anti-fascist, and having been persecuted in their country of origin.” Koestler doesn’t pretty up their political views or personalities; they are disillusioned, sometimes prejudiced, with odd judgments. But each had resisted the Nazis and plainly would have continued to do so. The French Republic, “their natural ally,” nonetheless “abandoned and betrayed” them. Koestler shows us the psychological effects of internment and how the prisoners’ capacity to resist was destroyed: once courageous dissenters became so demoralized that they were simply “thankful that they were not shot.” Le Vernet was not Dachau, or Auschwitz; it was not at the heart of the Nazi terror. But Koestler and those who were interned there had witnessed ten years of defeats: electoral failure and political terror in Germany, mayhem in Austria, persecution in Poland, military downfall in Spain, and so on. “The essence of politics is hope,” writes Koestler, “and hope had gone.” Scum of the Earth covers only one year, but it makes this larger, sad story of Europe’s surrender to Hitler human and real. Fortunately, we know that 1940 was not the end of the story.

Photo Credits

Arthur Koestler, 1948, by Pinn Hans (www.gpo.gov.il) (Public domain) via Wikimedia Commons

Clandestine photo of Le Vernet, photographer unknown