By Sumit Guha

Nothing seems easier than remembering. Each of us remembers a great deal – from the recent past and the remote past. And even if we cannot remember something it surely is recorded somewhere in a collective memory – perhaps in the vast ragbag of information, disinformation, and speculation to be found on the internet? But once we think of verifying what we remember, we find that we are all – including the most eminent – sometimes mistaken. As the forensic psychologists Loftus and Doyle describe it,

“Sometimes information was never stored to begin with. Sometimes interference prevents memory from emerging to consciousness. Sometimes witnesses wish to forget; sometimes they are temporarily unable to retrieve… Moreover, another force, known as a constructive force, is also at work. People seem to be able to take bits and pieces of their experience and integrate them to construct objects that they never saw and events that never really happened.”

With audiences of millions, true crime stories and celebrity criminal trials form the most widely consumed form of historical memory in the USA – and perhaps in the world – today. A criminal trial elicits and tests evidence to a standard that few historical narratives could consistently meet. Yet, as Loftus and many others have pointed out, they can generate false narratives, either though bad laboratory science or the frailties of eye-witness memory.

So where does that leave historians, they who deem themselves the custodians of authentic memory? Are we simply writing the most tedious genre of “magical realism,” as Alice suspected? Historians are not writing imaginary history, but they cannot transcend either the passage of time or the loss of knowledge. They must live in the society of their own time, with all the limitations that that implies.

All thought on this must begin with the work of the great French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs who was murdered in Buchenwald in 1945. Halbwachs sought to integrate the then emerging science of social psychology with his concept of collective memory. He wrote that we can remember the past only by retrieving the location of past events “from the frameworks of collective memory.” Almost a century of psychological research after Halbwachs has solidly supported his claim. “Remembering” is not an act of retrieval, but of reconstruction within a social group.

The reconstructive process is where mistakes occur, such as the implanting of false memories. Experimental psychologists have long known about false or implanted memory. But obviously, demonstrating falsity depends on our capacity to recover authentic truth. So if the memory claims to be a statement of fact, then it is open to interrogation – even first-person eyewitness narrative may be questioned. These have failed scrutiny more than once.

In reconstructing historical memory, scholars have often focused only on the high scholarship of the past, ignoring folk and popular modes of reconstructing pasts. The family estate, the clan, the village, up to the larger imagined communities of ordinary folk — these commonplace and everyday pasts also tell important stories At various times and places, such narrations occupied the whole space of historical practice: all history was non-professional history. It was also often consciously public, directed, for example, to establish present privilege through an inherited right. Only gradually was history that was based on claims to sanctity, honor, property, and taxation displaced by new histories written by professionals, at least in the confines of the formal educational system. That transition required the determination of the protocols of historical inquiry within the community of scholars.

Collective memory is defined by its public and societally monitored character. It is necessarily made and reproduced within a framework of social and political relations that create and bind a community of thought. It also follows that the disintegration of that framing community will also cause its social memory to vanish. Sometimes – usually in recent millennia, collective memory has left some legible trace in the historical record: more often it has not. That indeed, is what has happened to the greatest part of human collective memory: the bards and sages died and left no disciples. Inscriptions and monuments crumbled. Scribal traditions died out and scripts became illegible. In the past two centuries, that collective memory has increasingly, but not solely, been built by standardized and state-controlled education. It has also been deeply imprinted by any given state’s variety of nationalism.

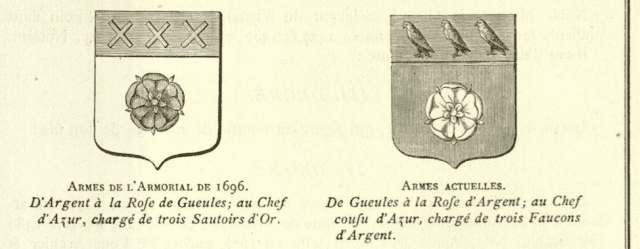

Collective memory was not trivial: it affected political life, criminal justice, and property claims in concrete and specific ways. It is a reconstruction that is socially sanctioned and institutionalized. In 1658, the noble Raymond de Gigord who carried the armorial symbols shown above had to prove his nobility to avoid a royal tax (franc-fief).

But before and alongside the modern state, many smaller social entities also provided frameworks for the organization of memory. Some operated by the creation of ‘micro-histories.’

Hero-stone commemorating warriors who fought large numbers of enemies to protect their herds of cows. (Sagar Borkar’s Blog. Used with permission)

The descendants of an impoverished lineage revived their claim some sixty years after fleeing their village during an invasion. They told the tribunal their story and authenticated it by referring to a well-known village monument:

“Our ancestors maintained their lordship through the generations, but we cannot discover who first obtained the right. In the days of Bijapur rule [i.e. before the 1650s] Krishna-shet son of Yesa-shet ran the lordship. Krishna-shet’s brother Sona-shet died in the village, his wife immolated herself, her masonry memorial is still extant in the village. Then Bhāg-shet son of Krishna-set managed the lordship.”

This hero stone commemorates a “sati,” a woman who burned herself on her husband’s funeral pyre. (Sagar Borkar’s Blog, used with permission).

Such episodes were recorded on the landscape in thousands of monuments, like the memorial shown immediately above and below, and at the top of the page. The local community would have preserved their hero’s memory and associated it with the stone. After the community is long since dispersed, the stones remain.

Historical memory is not only lost: it is also made anew by emerging communities. For the past two centuries and in a growing part of the world, such communities include emergent nations struggling against colonial empires. Nationalists sought to shape various alternative memories to fit their own future projects. The departure of the British Empire from South Asia left its apparatus of schooling and research in new hands. That is the frame in which modern practices of historical memory were shaped in nineteenth and twentieth-century South Asia and elsewhere. But they exist as bubbles in the stream of other narratives, some concocted for entertainment, some for more sinister purposes.

For more on history and memory in India, see Sumit Guha’s new book: History and Collective Memory in South Asia, 1200-2000.

Suggestions for further reading:

Maurice Halbwachs On Collective Memory. Edited, translated, and with an introduction by Lewis A. Coser. (1992).

This was written in the 1930s and essentially founded the study of historical memory. It contains a particularly important study of the remembered and imagined topography of Jerusalem that later Christians sought to find and sometimes implanted.

Yosef H. Yerushalmi Zakhor: Jewish History and Jewish Memory. (1982).

This book studies not only the textual record of a community that preserved and expanded it for 2500 years, but also develops an elegant explanation of why it took the shape that it did.

Prachi Deshpande. Creative Pasts: Historical Memory and Identity in Western India, 1700-1960. (2007).

Tracks a continuous tradition of historical memory in Western India and illustrates the leakages from tradition to historical text to theatre and novels in a major Indian language, Marathi.

Christian L. Novetzke. Religion and Public Memory: A Cultural History of Saint Namdev in India. (2008).

Novetzke tracks the many textual traditions and performative oral memories of a pan-Indian religious figure through seven centuries.

Indrani Chatterjee. Forgotten Friends: Monks, Marriages, and Memories of Northeast India. (2013)

Shows how a religious tradition and network were erased under the pressures of colonial conquest and a new set of identities and memories were implanted under the joint pressures of Western anthropology and Protestant missionary enterprise.

Header photo credit: Shreyans Vasa, Memorial in Chhatardi, Bhuj, India (Wikipedia)