From the Editor: This article is part of a wider series that explores how teachers and students across the History department, the university and world more generally are responding in new ways to the unprecedented classroom environment we face in a time of global pandemic. The goal is to share innovative resources and ideas with a focus on digital tools, scholarship and archives. This article is one of a number exploring ClioVis, an innovative digital timeline tool developed at the University of Texas at Austin by Dr Erika Bsumek. As we all struggle with online teaching and how to engage students in a virtual classroom, there is a need for reliable technology that allows students to collaborate effectively while interacting with historical sources. Here ClioVis is enormously helpful, providing students with new ways to organize complex information and to show historical inter-connections. Below Dr Bsumek is interviewed by Adam Clulow as part of Not Even Past Conversations. Although UT has a professional recording studio, this conversation, like so much today, was recorded via Zoom. It has glitches and the sound or image quality drops occasionally, but in this current moment we feel that it is more important than ever to hear directly from teachers and scholars. This interview can best be read alongside A Year in Time: The Student Experience of ClioVis and ClioVis: Description, Origin and Uses.

AC: Can you introduce ClioVis to someone who is not familiar with it?

AC: What is the inspiration for ClioVis and what problem does it set out to solve?

EB: The inspiration was twofold. ClioVis emerged from my research and my teaching. I was researching the history of technology and I was thinking about how water and irrigation technology evolved in the 19th century — and all the historical forces that shaped dams, irrigation ditches, and so on. People in tech build something called ‘technology trees’ to track changes from the tech side. And, technology trees are interesting, they represent the relationship between different technologies. Since I was researching dams on the Colorado Plateau I was exploring how people told the story of the evolution of that particular technology. But, I wanted to enhance my understanding of technology and include social, political, cultural and economic forces as part of the history of technology.

At the same time, I was teaching a class on the history of infrastructure in the United States and how it had transformed society. I was interested in helping my students better understand how technology evolved and how it was connected to different cultural transformation and social transformations. So I was I was trying to find a piece of technology that was like the technology tree but had a little more flexibility where students could actually look into, explore, create, build a historical timeline of how things evolved in society. I wanted them to be able to make connections and explain them. The format needed to be very flexible. So that was the inspiration. It came out of my research and my teaching.

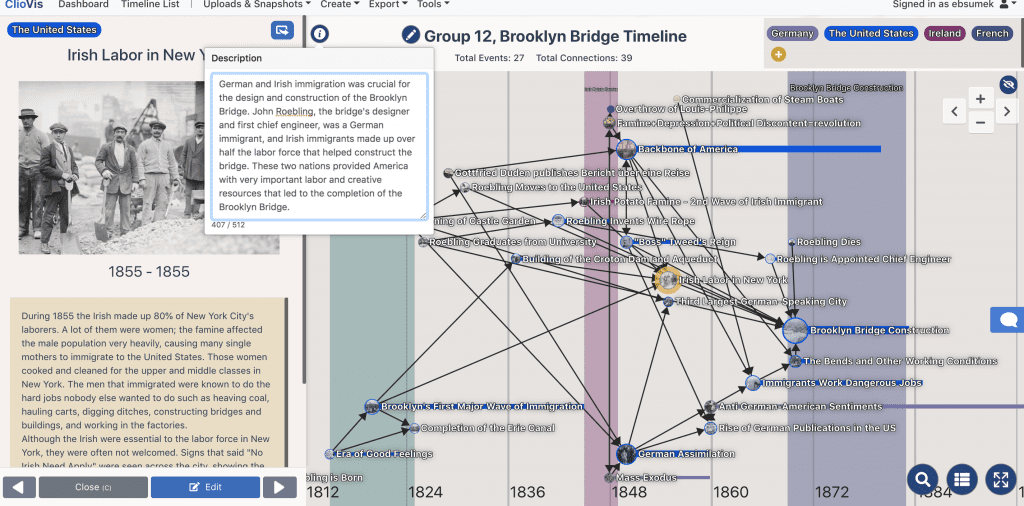

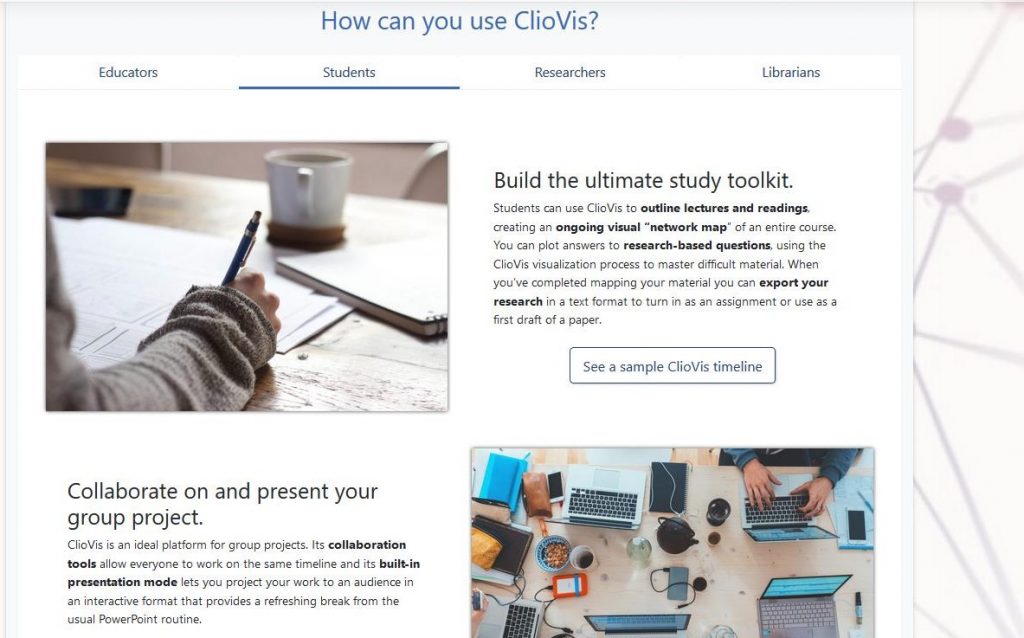

And then there was a larger problem that I was encountering in the classroom. The key problem that ClioVis solves — or one of the key problems that it solves — is that it helps students actually connect what they’re learning, they connect specific historical events to broader social and cultural transformations. In the way the software functions, students can plot events and then make connections. They have to actually explain the relationship between events when they create the connection. So that’s the first problem. The second problem is we get a lot of students with what I might call a skill gap at the University of Texas. Many are taught history through memorization. Historians don’t really think about history as memorization. We think about embracing complexity and trying to understand relationships between things. And so that’s the second problem that ClioVis solves. It’s is teaching students how to think historically through their understanding of complex relationships. Learning history by thinking about relationships makes it far more interesting than memorizing a bunch of dates and facts. In the education world, it means we are taking an constructivist approach to teaching!

AC: In talking to you, I’m reminded of the kind of timelines that I know so well from high school textbooks in which they show events in a linear line. Can you talk about some of the issues with conventional timelines in terms of over-simplifying the complexity of historical events?

AC: Why are such skills especially important for students in large first year courses who are new to university and university education?

EB: There are a lot of studies that show that performance in lower division history courses – what people in education call gateway courses – are, regardless of major, key indicators of success. And success is defined as graduation within five years. The rate of failure or withdrawal from lower division history classes across the U.S. is extremely high. The overall average tends to be about 25% of students in the United States, meaning that we are potentially leaving behind a huge number of students by not helping them grasp the fundamentals of historical thinking. So historical thinking turns out to be really important for success, not just in history classes, but in classes beyond history — for all majors at a college or university.

AC: And do you find that when students use ClioVis, that it changes the way they think about history? This was my experience with students in my class. Once they start to work through these messy timelines, it creates all sorts of new questions. So they identify an event but then they start to think about what contributes to that event or what flows on from that event.

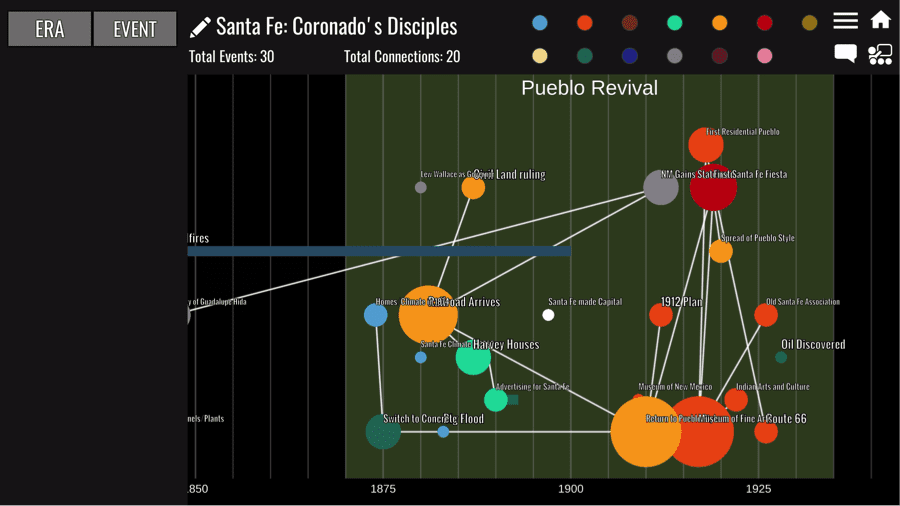

EB: That’s been really exciting for me to see students begin to embrace a new way of historical thinking. When they use ClioVis they not only plot events, they begin to see when things happened, but when they make connections they also begin to see history as a network of different events that can be connected in different ways. I see a lot of students who have just never even tought about the past in this particular way. They just are so coached through K through 12 education to think of history as a sort of series of events with specific narratives attached to them. And, those narratives can be kind of contentious. So for them to begin to plot things on their own they actively engage with the past. They’re not just reading and memorizing and giving an answer back to a teacher. Instead they are engaging with the material, paraphrasing it, thinking about where they’re getting their evidence and they think about what that evidence is when doing this!

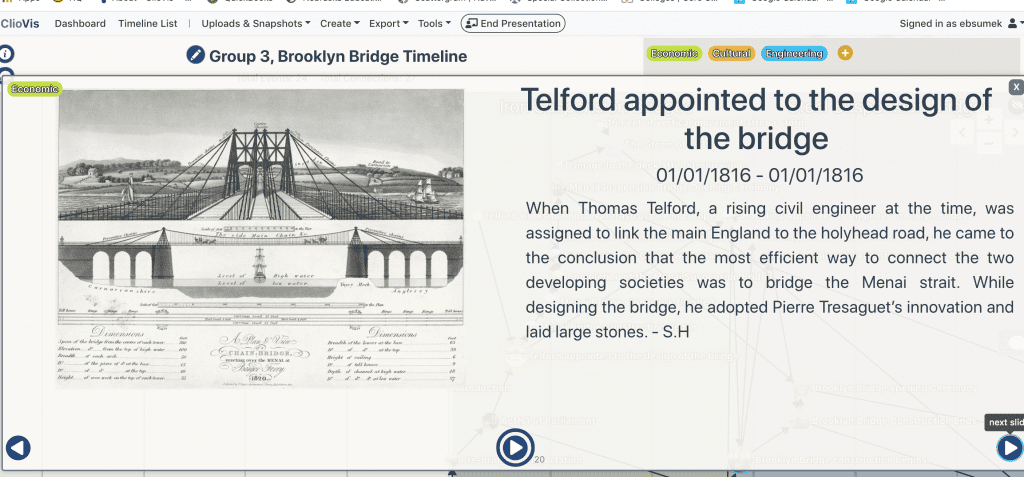

So we’re really teaching them about evidence based learning along the way, we are asking them to justify the connections they’re making based on the evidence that they’re using and then to consider alternative interpretations. For many of the students that’s the first time they have done this. When they to learn history in this way its more fun and interesting. They find images and sound clips, they work collaboratively in groups and talk to each other. They have to decide what set of connections they’re going to use in the timeline. They make a this kind of living thing – an interactive timeline. They can even create a little mini-documentary along the way. They had made a product they can share with family members or friends. In my experience it has been very exciting.

AC: What has been the process of developing Cliovis?

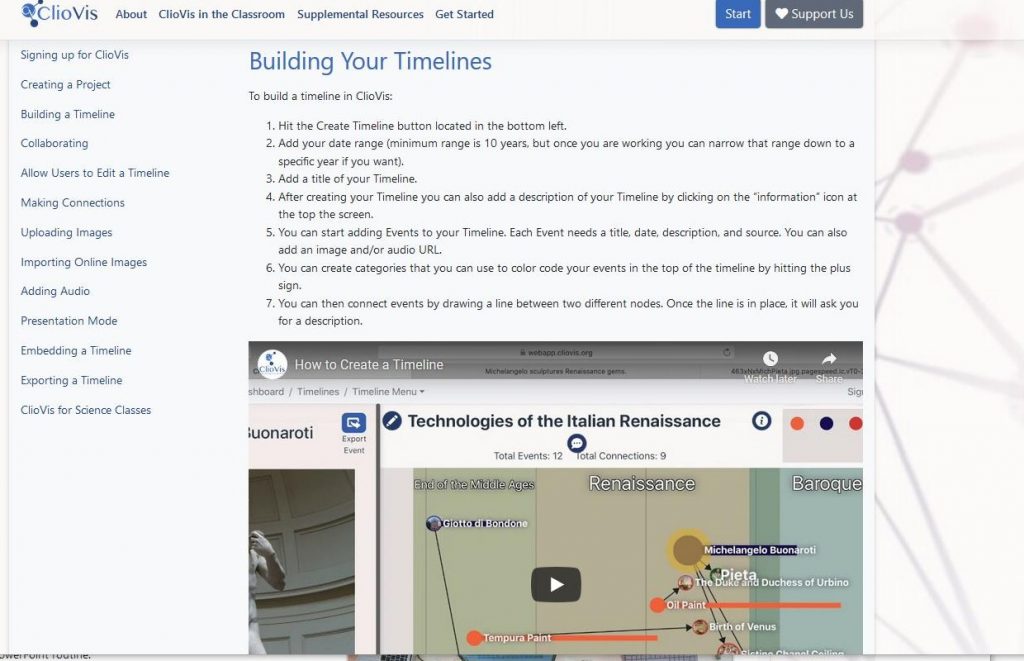

It has been a long process and a really interesting one for me because I didn’t have any background in technology. Initially I thought I would just find some technology that did what I wanted it to do, and then I realized it wasn’t out there. So then I got a small grant from UT to build a prototype. I worked wit SAGA Labs on campus and we built the first prototype which my students in that technology class used — and they had a great time with it.

The students really got into it and did these wonderful in class presentations. And, then I showed their work to a few people and other people were interested in using it. So Matthew O’Hair, Ian Diaz, and Braeden Kennedy and I came up with a sort of version 1A that was a little more user friendly — and since then it’s just kind of taken off. I originally had to learn a little bit of coding. I’ve had to learn about website construction. I’ve had to learn about working with technologists who sometimes think very differently from historians. The way that they solve the problem is very different from the way that I would solve a problem so it’s been really fruitful to learn about how others think and work. It’s been an interesting experiment in cross or interdisciplinary thinking, and it turns out we have a lot to contribute to each other. It’s also a very time consuming process.

AC: What has your experience been as a historian working with and developing new technology?

EB: I think this was an interesting lesson for me as a humanist to work with people in technology. We have access to technology and it works immediately. We turn on our computers. They work. They do the things we want them to do. We turn on our phone. We can do all these amazing things with it. And I think people have the perception as a result the work designers have done that building and making things with technology is easy. But it’s not, especially when you’re building something from the ground up. You have to understand the limits of technology that exist and the time that goes into building that technology. Then, you have to learn how you can surmount those problems. Then you get a product and you iterate, it’s just an iterative process continually.

OK, we did this. Now can we do that? You know, there’s a pace at which that process moves which is both a lot faster in some ways than writing a book because something is always happening. We all work on it for four weeks. And we get one feature or something that’s pretty basic. And then we think, oh, wait, but it also needs to do X, Y and Z. And then we go back and we collectively work on it and everybody tests it out. So it it both moves glacially slow, but also really fast at the same time, because everybody is collaborating and learning at the same time. When writing a book or an article, you are working alone. You have to piece together evidence, track it down, organize it into a narrative. It’s a lot of self-reflective work. This is a bit more dynamic – but it’s also a tremendous amount of work.

AC: How is ClioVis being used in classrooms at the moment? Perhaps in ways that you anticipated but also in some that you did not?

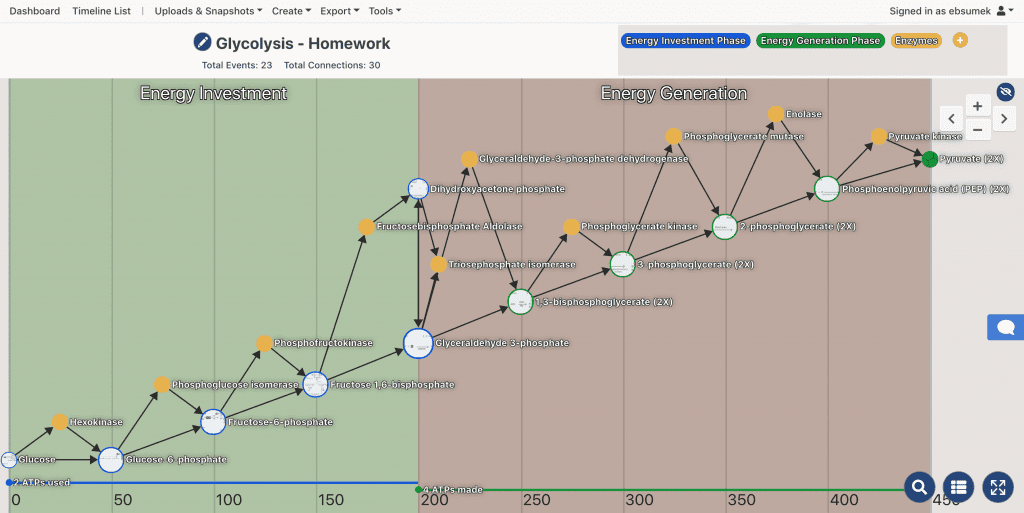

AC: This sounds incredibly exciting. You started with historical skills, but ClioVis has now expanded to different disciplines. So that’s bigger, more ambitious but also very exciting. What has ClioVis taught you about skills beyond the History classroom?

I think we talk a lot about critical thinking and transferable skills in academia. They have become catch phrases that we use all the time. But for me I find that this is the real thing ClioVis does, it demonstrates that the value of critical thinking, learning how to think critically, how to organize information, how to make analytical connections transcends any one discipline. You learn how to write, how to think with evidence. All of those things are things that you use in different disciplines, which is what I think that “gateway study” tells us, right? Why are history courses are gateway courses? Because the skills that you learn there, in those courses, from mastering basic historical thinking, to learning how to communicate and convey what you’ve learned back to someone — those are skills you will use in any course across campus. And they’re also skills that you would use in any profession. So it really is like stepping students into this process, teaching them, guiding them, encouraging them along the way to become critical thinkers.

I think in the humanities we sometimes undervalue ourselves and what we do and how it applies to the core mission of the university. But thinking about pedagogy has made me realize how important what we do really is, not only for us, but for our students across disciplines. And, that is very exciting for me. I think it I sends a message to other humanists that they should also do these kind of things – invent tools! I’ve done a lot of research into Educational Technology, which is an exploding field right now. Humanists should be at the table in these discussions, we should be at the forefront. We shouldn’t let people coming straight out of STEM be the only people inventing tech. We should be at the table in these conversations because it’s helpful for our disciplines, our students, and our educational establishments, I think, to have us there.

AC: So we can have a technology that is used on Monday in a history classroom and on Tuesday it can be used in a science classroom. It really moves us completely away from this idea of humanities skills as being different from what students learn in a STEM classroom. Have you found that STEM students start to think differently after using ClioVis?

I think it amplifies the need to make connections. When students leave their history classes and go into their STEM classes, they can think about how a concept that they are learning about in both classes are connected, and how both influence society. And so one of the things that I hope happens, at least with my class when I teach the history of technology is: what are the social and cultural implications of the technology that you are studying? So there’s a great quote that I have my students read from an engineering professor in the 1960s. He’s talking about some big debates in education — and engineering education. And he says, ‘well, we could train engineers to drain the Atlantic Ocean, but we should also train them to ask: should we do that?’ So his quote makes us think in terms of connections. What is everything connected to? Right? And what are the broader implications of new technologies? We can make something in a in a laboratory and we can create it and test it out but what are the [potential] ethical problems? How is it going to change society if we make it? And, I know technologists are beginning to have these debates but if we have students who think this way, it expands what we can do [as a society]. And, it demonstrates how important what we do is to the rest of the university, I think, and beyond to the rest of society.

AC: Are there any recent ClioVis projects that you found particularly exciting that you could introduce briefly to us?

Thank you for talking to me today and congratulations on the success of ClioVis.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.