This and other articles are part of a new collaboration with the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History. Visit the Briscoe’s website to learn more about its collections. This article first appeared in CenterPoints and is reprinted with permission here.

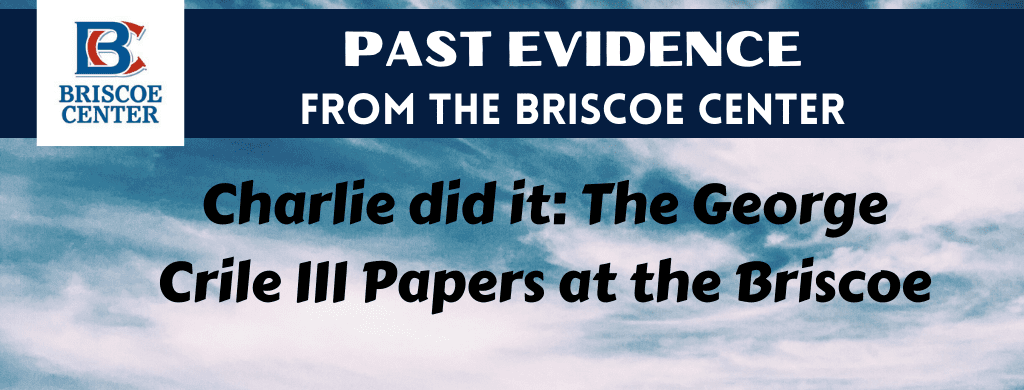

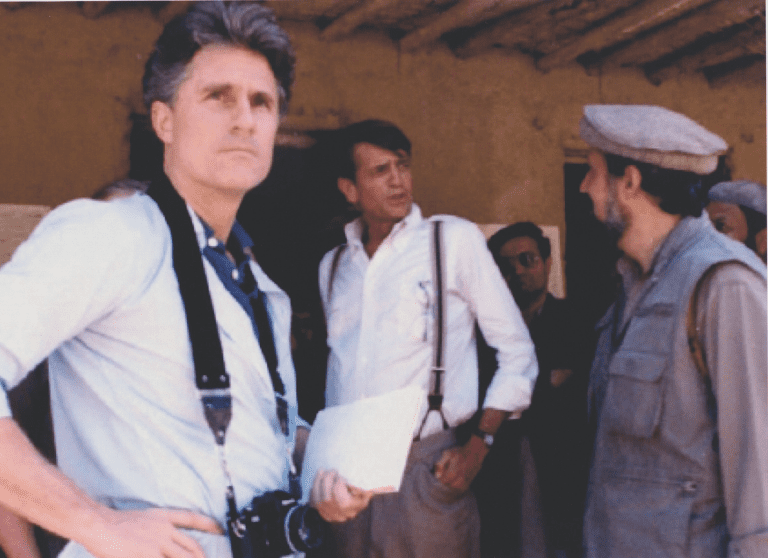

During the 1980s, the United States government provided covert assistance to the Mujahideen, an Afghan rebel force engaged in armed revolt against their Russian occupiers. At the heart of these clandestine efforts was a not-so-covert Texan, Congressman Charlie Wilson. 6’7” in his boots, Wilson made multiple trips to Afghanistan between 1982 and 1988, where he was greeted as a hero. The reason—Wilson’s wheeling and dealing in the U.S. House of Representatives as a member of the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee enabled millions of dollars in equipment and supplies to be funneled to the rebels.

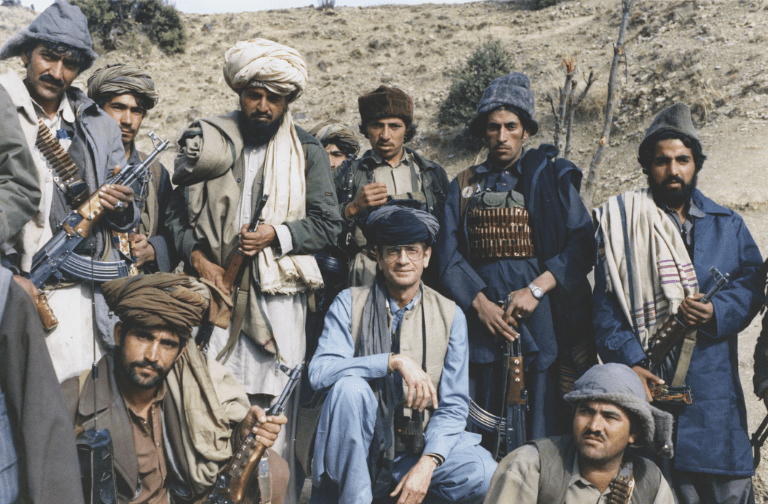

Of particular value was the “stinger,” a shoulder-mounted anti-aircraft missile launcher that could shoot down a $20 million Russian helicopter gunship from three miles away. By 1988, over 100 of these had been smuggled into Afghanistan, and the Mujahideen were averaging one chopper down per day. Before the stinger, both militants and civilians had been sitting ducks for Soviet forces on missions. In large part thanks to Wilson, the war was now a fairer fight, one the rebels were winning.

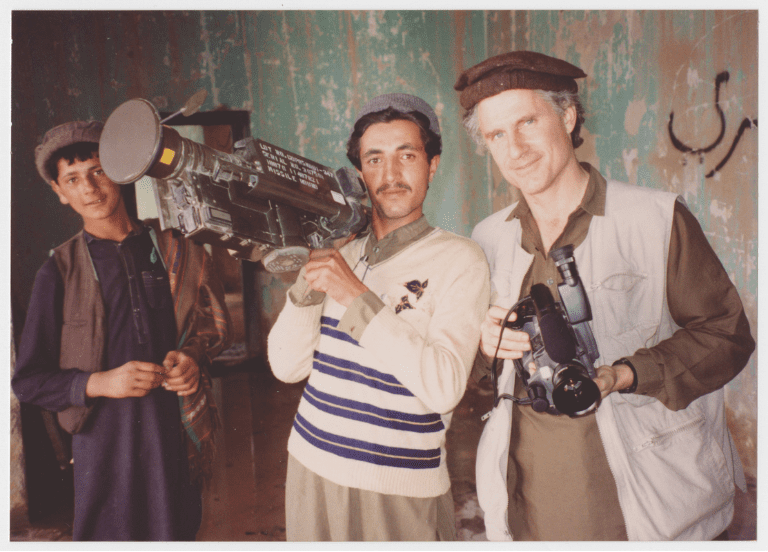

“Not everyone is comfortable giving stingers to fundamentalist Muslims,” explained Harry Reasoner while presenting the 60 Minutes segment “Charlie Did It” to a prime-time audience in October 1988. But the stinger and other equipment, continued Reasoner, meant that “America was doing to the Russians in Afghanistan what the Russians did to us in Vietnam.”

“Charlie Did It” was produced by George Crile III, whose papers are now housed at the Briscoe Center. Crile specialized in difficult topics, often involving foreign countries. In 1976, he produced “The CIA’s Secret Army,” which focused on the agency’s involvement with the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in 1961. In 1978 he won a George Foster Peabody Award and an Emmy for his documentary, “The Battle for South Africa.” His most controversial report, “The Uncounted Enemy: A Vietnam Deception” (1982), led to a $120 million lawsuit for alleging that General William C. Westmoreland had deliberately underestimated enemy troop numbers during Vietnam.

By 1988, Crile—a former marine reserve—was a veteran journalist. “Charlie Did It” showcased the full range of his talents as a researcher and producer, from his ability to befriend Wilson and eke out information to his framing of America’s involvement in Afghanistan as payback for Vietnam. “Nobody enjoys the anguish of a twenty-year-old [soldier] from Leningrad, what he goes through,” confided Wilson on camera. He then straightened his posture, morphing his musing expression into a frown. “But 167 boys from East Texas, from my little district [died in Vietnam] and they didn’t have anything to do with it either. . . . I love sticking it to the Russians.”

Thirty years later, Crile’s piece on Wilson stands out for its striking, casual candor. At one point, Wilson points to a stinger above his office door in Washington.“Please don’t ask me how I got it back here,” he says with a wry smile. From the project, Crile kept pictures, letters, interview notes, and video recordings as well as now-declassified dossiers and expenditure sheets that show how Wilson managed a foreign policy relationship between the strangest of bedfellows. Crile gathered enough material to write a book, Charlie Wilson’s War (2003), which in 2007 was made into a movie of the same name.

A story of Greek proportions—equal parts comedic, dramatic, and tragic—the evolution of Crile’s report into a book and film is no surprise. But this side of 9/11, the story raises troubling questions. In 1989, the Soviet Union pulled out of Afghanistan and then collapsed. The mountainous Muslim nation lay in tatters, but America moved on. Wilson’s advocacy in Congress to fund rebuilding efforts met little enthusiasm. Instead, Afghanistan became a breeding ground and staging post for fundamentalism and terrorists.

“The Taliban was a result of the United States, with our usual attention deficit disorder, leaving before it was time, leaving the job before it was finished,” said Wilson to Mike Wallace in 2001 in a 60 Minutes episode that reprised Crile’s 1988 investigation. “I bear as much responsibility for that as any person alive . . . it’s as if we had walked away from Europe in 1945… what we needed here was a little mini Marshall plan.”

Crile went on to produce a number of other stories for CBS about the Middle East, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. Along with Crile’s many other projects, they are well documented in his papers. The archives of news media professionals do not simply recount how people reported on and thought about politics and foreign policy in the past, but also how perceptions have changed. Today, they resonate in surprising, unexpected, and darkly significant ways. What exactly was it that Charlie did? The answer to that question continues to evolve.