Megan Kate Nelson has written a captivating history of the southwestern theater of the American Civil War. There more than one war took place as different groups of people envisioned futures dependent on control of the region. The balance of perspectives makes it clear the Civil War was not just a battle for the preservation of the Union, or for those states that had seceded, but rather a multicultural war for control of much of the North American continent. The Union, the Confederacy, Mexico, the Apache, and Navajo (Diné) all fought for control of land, water, resources, and trade. Skirmishes in the West were layered contests among several parties. While historians often acknowledge the importance of the West in determining the fate of slavery in an expanding nineteenth-century United States, few have tackled the southwestern theater as Nelson has in The Three-Cornered War.

Nelson’s writing is largely narrative and caters to a more popular audience. The layering of history compels the cultural, borderlands, and environmental historian while the details of battles captivate the military history enthusiast. Excerpts from letters and diaries as well as summaries of dialogue entertain those hunting for good stories. Nelson recounts an epic Western tale with a contemporary scholastic skillset that earned her a nod as a Pulitzer finalist in 2020.

The book balances several viewpoints of the conflict, including the perspectives of men and women, Unionists and Confederates, Mexicans, and Indigenous people. She adjusts the perspective with each chapter, unfolding the narrative through a different person’s viewpoint every ten or fifteen pages. People, rather than larger-than-life forces, are at the center of this story about power and property in the Southwest.

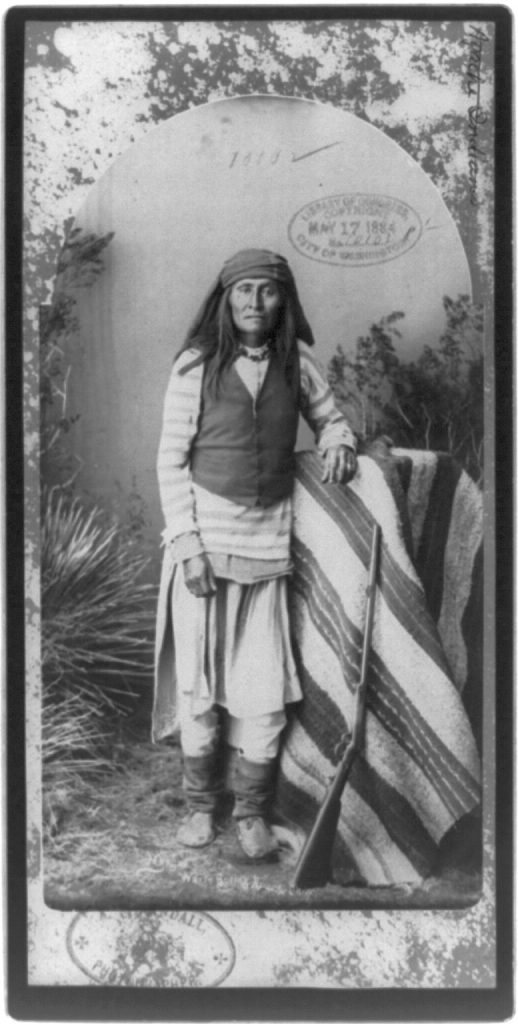

The book uses the stories of nine individuals to detail the battles between nations, armies, and ideas in what would become the Southwestern United States. Those people are: Mangas Coloradas, Apache leader; Juanita, wife of Diné warrior Manuelito; Alonzo Ickis, miner turned Union soldier; John Clark, New Mexico Surveyor General; Louisa Canby, wife to Union Colonel Edward Richard Sprigg Canby and nurse to injured soldiers; James Carleton, Union Colonel; Kit Carson, Southwestern frontiersman and Union Brigadier General; John Robert Baylor, Confederate Brigadier General from Texas; and Bill Davidson, a Confederate soldier and Texas lawyer.

If there are any characters missing from this story, they are African Americans, whose fate in the West was in the balance (as Nelson reminds us). She notes that enslaved Blacks in Confederate held Arizona Territory were few and mostly held by Confederate military officers (83). Slavery in The Three Cornered War focuses on Mexican enslavement of Indigenous Americans. However, the reader is left to assume the Confederate vision of empire would expand the system of race-based enslavement as far west as California. This vision could have also included enslaving Indigenous Americans had the Confederate States of America endured.

The Three Cornered War concentrates on the events between 1861 and 1868, with background details for Nelson’s main characters inserted as needed. The eastern theater of the war appears only as snippets of news. The Southwestern theater was a set of wars all its own. Not only were the Union and the Confederacy competing in their visions of manifest destiny, but Mexicans fought to regain claims recently lost to the United States in the Mexican American War of the 1840s, the Apache fought to maintain Apachería, and the Navajo fought to maintain Diné Bikéyah.

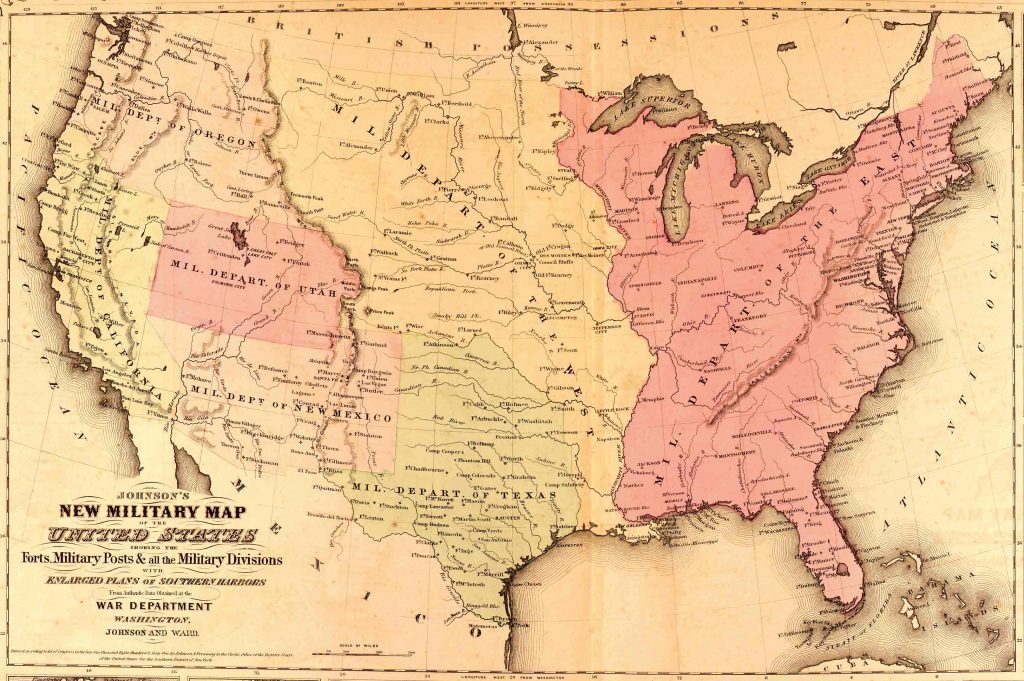

Nelson does not overtly discuss borderlands in the ways scholars of the field might desire, but she does evocatively illustrate the malleability of boundaries in the New Mexico Territory in the 1860s. Land changes hands, borders move, access to water, resources, and overland routes are contested, and recent wins and losses remain only barely settled in The Three Cornered War. This tension makes abundantly clear that the present-day borders of the United States were far from predestined. The Confederates had strategized a plan for their own transcontinental railroad to connect California to Georgia, and the rebels intended for slavery to flourish across the continent, perhaps even capturing more land from Mexico.

Unlike the skirmishes further east, armies in the Southwest were small: casualties could quickly devastate any of the bands of soldiers and warriors in conflict. The Apaches and Navajos fought to keep Anglos and Hispanos alike out of their lands. Mexican officials heard diplomatic pleas from both the Union and the Confederacy but attempted to delay decision making until a victor prevailed. The book includes several maps to help the reader situate the movements of these groups and the quickly changing landscape of the southwest.

Nelson makes clear that these contingencies often depended on the actions of military leaders who acted without seeking approval, in large part because there simply was not adequate time to communicate with distant officials before circumstances changed. Dishonorable and treacherous war tactics were constant, and seemed necessary, but could face delay or prohibition from central authorities. The southwestern theater was a place where men gambled with their lives, but the winnings made it worthwhile.

Though the Union won the conflict and control of the land, Nelson reminds readers this came at a price and made the United States’ objectives contradictory. She writes, “These struggles for power in the West exposed a hard and complicated truth about the Union government’s war aims: that they simultaneously embraced slave emancipation and Native extermination in order to secure an American empire of liberty” (252). The price for the eradication of race-based slavery in the United States was the very sovereignty of its native peoples. In this three-cornered conflict, the United States sharpened its blades against all in the name of liberty granted only on the Americans’ terms.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.