by Ana Cecilia Calle

In honor of the centennial of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, the 2022 Lozano Long Conference focuses on archives with Latin American perspectives in order to better visualize the ethical and political implications of archival practices globally. The conference was held in February 2022 and the videos of all the presentation will be available soon. Thinking archivally in a time of COVID-19 has also given us an unexpected opportunity to re-imagine the international academic conference. This Not Even Past publication joins those by other graduate students at the University of Texas at Austin. The series as a whole is designed to engage with the work of individual speakers as well as to present valuable resources that will supplement the conference’s recorded presentations. This new conference model, which will make online resources freely and permanently available, seeks to reach audiences beyond conference attendees in the hopes of decolonizing and democratizing access to the production of knowledge. The conference recordings and connected articles can be found here.

En el marco del homenaje al centenario de la Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, la Conferencia Lozano Long 2022 propició un espacio de reflexión sobre archivos latinoamericanos desde un pensamiento latinoamericano con el propósito de entender y conocer las contribuciones de la región a las prácticas archivísticas globales, así como las responsabilidades éticas y políticas que esto implica. Pensar en términos de archivística en tiempos de COVID-19 también nos brindó la imprevista oportunidad de re-imaginar la forma en la que se llevan a cabo conferencias académicas internacionales. Como parte de esta propuesta, esta publicación de Not Even Past se junta a las otras de la serie escritas por estudiantes de posgrado en la Universidad de Texas en Austin. En ellas los estudiantes resaltan el trabajo de las y los panelistas invitados a la conferencia con el objetivo de socializar el material y así descolonizar y democratizar el acceso a la producción de conocimiento. La conferencia tuvo lugar en febrero de 2022 pero todas las presentaciones, así como las grabaciones de los paneles están archivados en YouTube de forma permanente y pronto estarán disponibles las traducciones al inglés y español respectivamente. Las grabaciones de la conferencia y los artículos relacionados se pueden encontrar aquí.

Cristina Rivera Garza’s work is broad, playful, and fertile. Winner of national awards such as the Juan Rulfo prize and international awards such as the Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz prize, her name, ideas, and books appear in conferences, bookstores, literary conversations, and bedside tables more and more frequently. Lucky us. From her first short stories and novels, such as La guerra no importa (1991 San Luis Potosí Short Story Prize, 1987) or Desconocer (1994, Juan Rulfo prize for best first novel), critics and readers have received her hybrid prose with surprise and admiration. Rivera’s work shifts between literary genres, and her characters emerge from fragmentary narrative structures. Her work opens new ways of inhabiting reality, depicting its distortions, pondering grief and delirium, and constructing the archive as a way of living with our dead.

In No One Will See Me Cry (1999), the character of the photographer Joaquín Buitrago turns to the life of Matilde Burgos, a sick woman from the La Castañeda sanatorium in Mexico City, whom he thinks he recognizes when he visited a brothel in Mexico City. Matilde’s madness and suffering are a way of diving into early twentieth century Mexico, understanding her madness as a desire to “leave behind” all the pain inflicted by the Revolution, and Buitrago’s relationship with Burgos as a way of mirroring his own suffering in her pain.

Rivera Garza has stated that the “form” of her texts results from the writing process itself. Writing is a way of “being with” the story. The “shape” or “form” of the text emerges from that particular relationship. The corpus of her work is articulated as the arms, legs, and lungs of a body. I use this image to echo her idea of writing as an activity that happens through the body. Placing writing as a product of the body allows her to distance herself from traditional images of a lonely, gifted, and isolated writer. It also allows us to contemplate her work as coming out of a physical entity and, as such, capable of directly affecting the reality that surrounds it. As she describes in one of her Infraensayos, writing is “stopping in the middle, highlighting the middle […]. Language. A form of corporeity. Stop. Enjoy. A fingerprint.”

From a more theoretical perspective, Rivera Garza’s thinking aligns with what Argentine theorist Josefina Ludmer calls “post-autonomous literatures,” a point she has made in conferences as well. These works of literature no longer follow the concept of literary autonomy as a guiding principle nor the idea that literature has no direct influence in the world. For Ludmer, post-autonomous writing redefines the boundaries between what is considered literature and not. In her words, “it does not matter whether [post-autonomous literatures] are or aren’t literature. And it is not known, nor it does not matter if they are fact or fiction.” As Rivera Garza’s readers witness in her books, her writing jumps from genres associated with the “real” (ethnography, non-fiction crónica, or memoir) to self-fiction or novel. This torsion allows for the category of the “present” to reach new meaning.

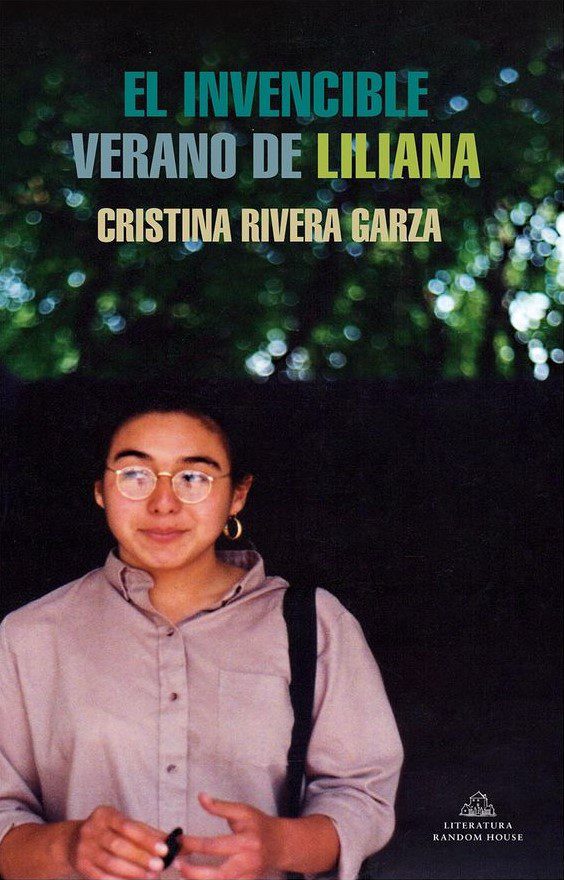

Another key theme in Cristina Rivera Garza’s intellectual production is the will to rewrite. This exercise been central to her literary and educational project since her first books. Writing as re-writing appears in two of her most recent works, Autobiografía del algodón y El invencible verano de Liliana. In rewriting, voices from the past can be heard and re-read, and the archive allows us to re-tell our own story. Voice from the past reappear and walk with us in our present. Faced with the impossibility of finding the judicial file regarding the death of her sister Liliana, who was murdered on July 16, 1990 by her ex-boyfriend Ángel González Ramos, El invencible verano de Liliana dialogues directly with Liliana’s voice. Cristina reconstructs her sister’s last years through her diaries, letters, and written drafts. Rivera Garza creates a “chorus” with the voices of those who most loved and knew Liliana.

This luminous gesture of creating an archive of affects using her younger sister’s writings, letters, and drafts, allows Liliana to live among us, her voice a cry for justice but also a testament of love and care. Feminism traverses this and other books: Liliana is a free woman. Her quest for freedom resonates; the violence inflicted on her body reappears on thousands of bodies of women every year. In this sense, the desire for writing and rewriting in Cristina Rivera Garza’s work is a “choral” desire, a co-authorship, an homage. Also, writing becomes a way to live in a present where the dead and the living coexist and conversate. In sum, writing for Rivera Garza is a policy and an ethics of care. It is not surprising that this choir-like capacity is at the core of recent projects, such as her digital humanities initiative. As she says elsewhere, we are “helpless when we are speechless.”

Cristina Rivera Garza will be a keynote speaker during the Lozano Long Conference entitled “Archiving Objects of Knowledge with Latin American Perspectives.” The conference helps celebrate the centennial of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, and is scheduled as a hybrid event that will take place from Thursday, February 24 through Friday, February 25, 2022. Although the conference will mostly take place online, Cristina Rivera Garza’s voice will be projected live and in person (and livestreamed) the evening of Thursday, February 24 from the Benson Library.

Ana Cecilia Calle holds a PhD from the University of Texas at Austin. Her dissertation, called “Along the Cumbia Beat. Literary, Cultural and Sonic Practices in Colombia and Argentina” has been funded by the Tinker Foundation and the Argentine Studies Center from the Lozano Long Institute for Latin American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. She is founder and editor of Himpar Editores, and dj’s with the all-women, all-vinyl collective Chulita Vinyl Club.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.