by James Hudson

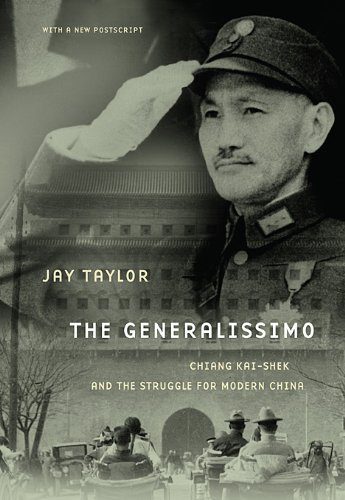

For many historians of China and even for many Chinese, Chiang Kai-shek, leader of China’s Nationalist Party and then founder of the Republic of China in Taiwan, was a classic “bad guy” of history. He was incompetent and ruthless. He cared little for the Chinese people or for those who worked under him. In popular history such interpretations of Chiang abound, but Jay Taylor’s biography casts the General in a different light, crediting Chiang with establishing and strengthening a faltering economy during a period of intense political and social turmoil. Taylor also observes that, while “Chiang could be heartless and sometimes ruthless, but he lacked the pathological megalomania and the absolutist ideology of a totalitarian dictator,” and regarding the potential of his own ideas was “more self-delusional than hypocritical.”

Chiang’s collaboration and subsequent rivalry with the Allied Commander in China during World War II, General Joseph Stilwell, was chronicled by Barbara Tuchman in her famous book, Stilwell and the American Experience in China: 1911-45. Although Tuchman portrays Stilwell as one of the most brilliant military minds of his generation, she often paints Chiang as nothing more than an inept tyrant, whom Stilwell affectionately referred to as “peanut.”

But Taylor provides Chiang’s side of the story, noting that the American general bore just as much responsibility for the nationalists’ failure to engage the Japanese and eventually defeat the communists, and that in the end Stilwell’s deep animosity for Chiang “clouded his judgment.” In this regard one also wonders if Taylor reaches too far. For instance, although he accounts for Stilwell’s impulsive character, he does not address the fact that all of the American commanders who worked with Chiang — Joseph Stilwell, Albert Wedemeyer, and even George Marshall, who eventually became Secretary of State—found him difficult to deal with. Some other leaders, such as Gandhi, Franklin Roosevelt, and commander of the Flying Tigers, Claire Chennault, found Chiang personable and charming. Such appeal was no doubt augmented by the influence of his wife. Educated in the United States and fluent in English, Madame Chiang Kai-shek remained her husband’s constant advocate throughout the war with Japan, representing the Nationalist Party abroad, even becoming the first woman to ever testify before Congress, pressing the continued need for American aid during World War II.

Perception of the seeming luxurious lifestyle of Chiang and his wife both at home and abroad at times strengthened and at times weakened the nationalist cause. But although the comforts enjoyed by Asia’s most influential couple may seem extravagant today, Taylor concludes that “luxury and constant attendance by personal servants, however, do not necessarily ruin prospects for a serious life. [Winston] Churchill all his life was dressed and undressed by someone else.”

For both popular as well as academic audiences, this book stands as a thorough and engaging read of a complex man and his leadership of China in the early twentieth century.

Photo credits:

Roberts, “Madame Chiang Kai-Shek and Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt are shown on the White House lawn February 24, 1943 during the former’s visit to the Capitol,” 24 February 1943

U.S. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black & White Photographs via The Library of Congress

You may also like:

Peter Hamilton’s review of Pearl Buck’s classic, Nobel Prize-winning book – and the first paperback bestseller – A Good Earth.