by Zachary Carmichael

This book is a wide-ranging study of the relationship between Bourbon Spain, its New World possessions, and the native peoples living on the borderlands of the Spanish empire who had not been brought under imperial political domination. Subjugating and Christianizing these unincorporated indigenous peoples, called bárbaros (translated as “savages”) were major objectives of late eighteenth-century Bourbon reforms. David Weber concludes that “pragmatism and power usually prevailed over ideas,” with Bourbon policy usually favoring a realistic approach to dealing with these native groups, alternatively using armed conflict or negotiation when each seemed most useful. The Spanish crown was only one of several interest groups—including Bourbon officials, the military, and the colonial bureaucracy—competing for the loyalty of indigenous peoples. Indians from geographically disparate Spanish borderland regions had more in common socially and culturally with each other than with the inhabitants of nearby colonial centers, like Mexico City or Lima. Weber justifies the range of his study by contending that others have looked at Spanish and native relations only from a local perspective, failing to account for the diverse challenges these groups posed for Bourbon rulers.

Subjugating and Christianizing these unincorporated indigenous peoples, called bárbaros (translated as “savages”) were major objectives of late eighteenth-century Bourbon reforms. David Weber concludes that “pragmatism and power usually prevailed over ideas,” with Bourbon policy usually favoring a realistic approach to dealing with these native groups, alternatively using armed conflict or negotiation when each seemed most useful. The Spanish crown was only one of several interest groups—including Bourbon officials, the military, and the colonial bureaucracy—competing for the loyalty of indigenous peoples. Indians from geographically disparate Spanish borderland regions had more in common socially and culturally with each other than with the inhabitants of nearby colonial centers, like Mexico City or Lima. Weber justifies the range of his study by contending that others have looked at Spanish and native relations only from a local perspective, failing to account for the diverse challenges these groups posed for Bourbon rulers.

Weber argues that Spanish imperial policy concerning unassimilated native populations changed for two reasons—Enlightenment thinking about the responsibilities that colonizers had toward indigenous subjects and Bourbon political restructuring. This fusion of Enlightenment philosophy and imperial directive is evident in the state-sponsored voyage of scientist Alejandro Malaspina along the west coast of Spanish America in 1789. Malaspina encountered numerous native groups and created a method to scientifically identify which groups were “savages.” As the Spanish explored and settled these borderland regions in the late eighteenth century, theworld of native groups changed permanently, and many resisted.  Weber analyzes these Indian societies based on how they defended their independence, rather than grouping them by geography. Yet, on the imperial periphery, cooperation and integration often came before conflict. Weber contends that the incompatibility between Spaniard and native was not as pronounced as other scholars have claimed. One successful tactic the Bourbons used to integrate native populations without open conflict was by taking over the independent missionaries, especially Jesuits, that operated in many peripheral areas. The book concludes by tracing the story of the indios bárbaros into the national period, a time in which the leaders of the new republics abandoned old Bourbon policies of negotiation. They came to regard independent natives as inferior peoples, and, in Argentina, the most radical case, actively exterminated the indigenous population.

Weber analyzes these Indian societies based on how they defended their independence, rather than grouping them by geography. Yet, on the imperial periphery, cooperation and integration often came before conflict. Weber contends that the incompatibility between Spaniard and native was not as pronounced as other scholars have claimed. One successful tactic the Bourbons used to integrate native populations without open conflict was by taking over the independent missionaries, especially Jesuits, that operated in many peripheral areas. The book concludes by tracing the story of the indios bárbaros into the national period, a time in which the leaders of the new republics abandoned old Bourbon policies of negotiation. They came to regard independent natives as inferior peoples, and, in Argentina, the most radical case, actively exterminated the indigenous population.

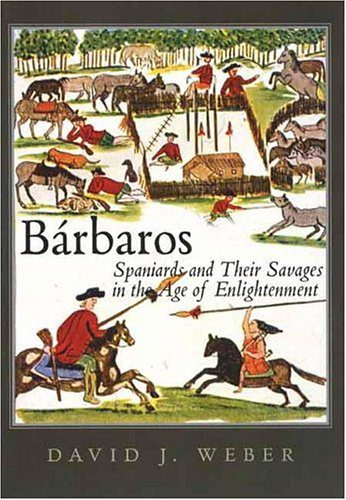

Weber succeeds in portraying the various strategies employed to deal with these semi-autonomous native groups, integrating diverse perspectives and geographic areas. The lengthy and detailed notes include annotations, translations, and a wealth of material that supplements the main text. Excellent maps included in the body of the book give the reader a geographic foundation to follow the many indigenous groups and frontier areas discussed. Weber could have integrated more local or native perspectives, but, in a book about government policy, this might prove distracting. Bárbaros is a groundbreaking study of Spanish and native relations. It has a well-defined scope, excellent research, and successfully defends the argument for Bourbon rulers’ pragmatic approach to dealing with unincorporated indigenous populations.

Photo credits:

Pedro Alonso O’Crouley, “Yndios Barbaros,” 1774

Biblioteca Nacional via the University of Illinois Department of Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese