Historians take a lot of notes, especially when it comes to our primary sources. For those of us who are fortunate enough to have access to digitized sources, our notes keep a record of our thoughts on the material in question and its use in our research. For those using sources that are not digitized (and will not be any time soon), notes are their lifeline. The time spent in archives can produce many notes, and they are as unique as the person writing them. Some historians stick to pen and paper, while others use a range of electronic methods. Still others take an overwhelming number of photos to dig through later when the push to see as much as possible in a short amount of time has subsided. A final group, which includes myself, takes both photos and notes and incorporates both into programs like Tropy, where I can take notes in more detail on specific photos and sources.

But what about historians that don’t rely on written records? How do you take notes on audio records from early recordings, vinyl LP records, tapes, or 8MM videos? Even those that have been digitized by archives are still not conducive to note-taking. When audio sources can’t be readily or easily used in research – even with something as simple as the ability to take clear notes or collaborate with others on researching a source – then the sources stay inaccessible. In some cases, archives and libraries may discard inaccessible sources in order to make room for sources that people are more likely to use.[1]

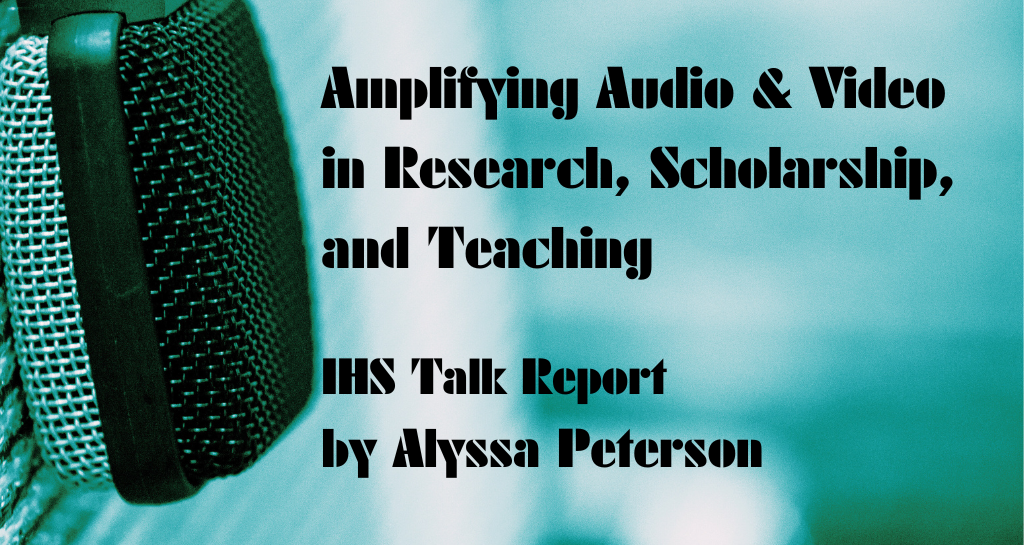

Dr. Tanya Clement and her team have created an easy-to-use tool that addresses this problem. In the talk “AudiAnnotate: Amplifying Audio & Video in Research, Scholarship, and Teaching,” given at the Institute of for Historical Studies (IHS) in October, Clement presented AudiAnnotate, and its newest sister, AV-Annotate, both applications that help scholars take notes on audio and visual records. The talk is part of this year’s IHS research theme, “Experiencing Place: Interrogating Spatial Dimensions of the Human Past.”

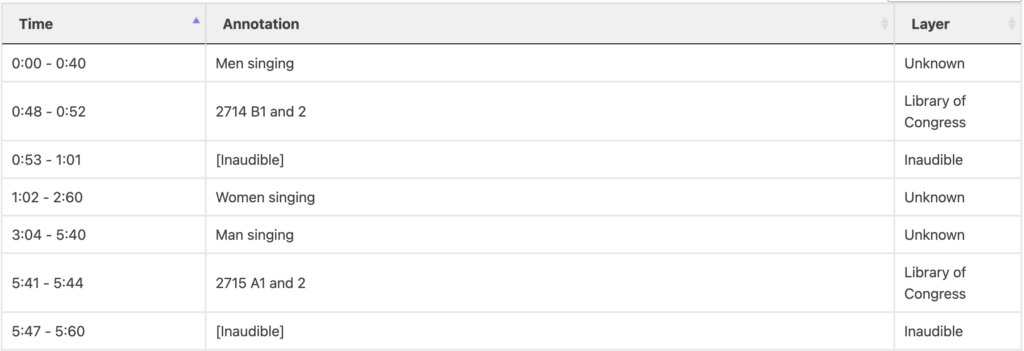

How exactly does AudiAnnotate work? Despite what you might think, the tool does not rely on a supercomputer or a massive database. Instead, Clement and her team worked hard to avoid making AudiAnnotate more complicated than it needed to be. AudiAnnotate uses GitHub, a free online coding and collaboration site. Users upload their sources to their GitHub repository. The tool then works like a layer placed on top of the source, which connects notes taken in a spreadsheet program to the original audio source. Once the annotations from the spreadsheet are added to the application, they automatically sync and pop up when the audio is played. The user can then follow the notes as the recording plays or go directly to specific points within the source connected with a specific annotation. Dr. Clement put together this example to demonstrate how the final result could look.

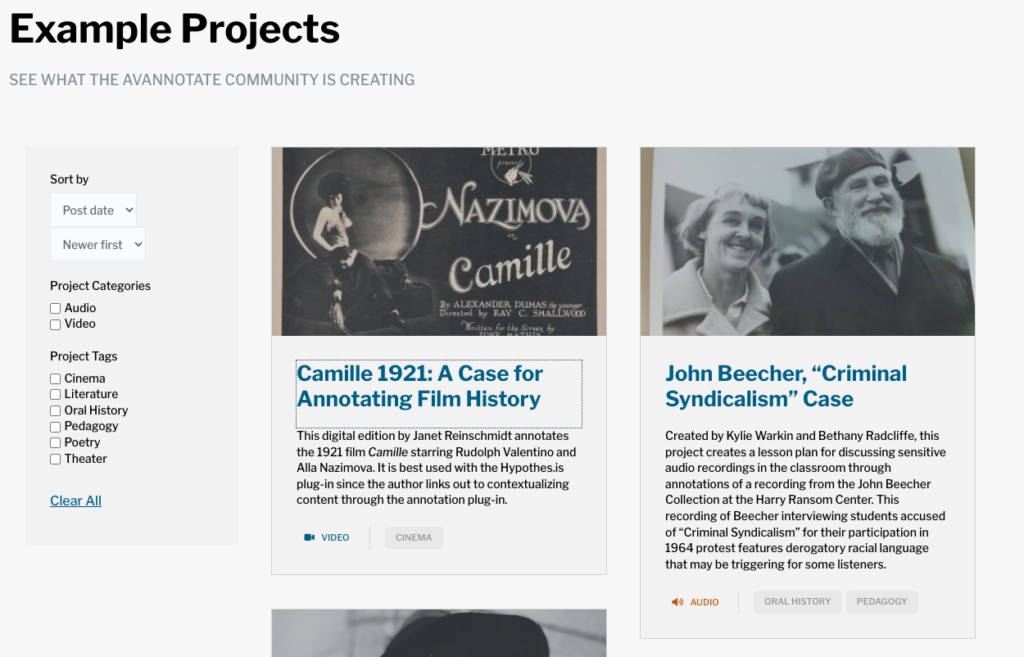

While taking notes on an audio source takes time, it is no more work than taking notes on written sources that are then added or transferred to different programs or applications. For instance, I use Tropy to take notes on written sources page by page. My notes are not automatically generated or connected to each page when I place the original source within Tropy; instead, I have to go through each page and enter my notes. However, when I go back through it later, the work has already been done, and I can find and use the information easily. The same goes for AudiAnnotate: by inputting the annotations and completing all the work upfront, the notes are then easily and readily available for future use. Like many other note-taking programs currently available, there are step-by-step instructions for how to get started and use AudiAnnotate, as well as example projects that demonstrate what the program is capable of when used by researchers.

Because there is no sprawling, expensive-to-use database, and the underlying platform is a free repository, there is no cost to use AudiAnnotate, which is great for academics or history enthusiasts, who often struggle with high user costs. There is also no fear of the program losing or clearing the information you created or holding it hostage behind a paywall of some kind. By using GitHub, all notations made within the AudiAnnotate “layer” stay in your personal GitHub repository. Thus, AudiAnnotate designers have no access to individual repositories, and all information will stay within your own repository until you delete it on your own. The program also creates a static (i.e., unchanging) and sharable “webpage” for the source and notes, allowing scholars to have a stable way to view their work while also allowing collaboration on projects.

AudiAnnotate is great for classroom collaboration projects. Programs like Perusall (for written texts) and Hypothesis (for websites) allow for collaborative note-taking and have been used to engage students with subjects and sources in various courses. AudiAnnotate can be used in similar ways, from demonstrating knowledge of film techniques or critiquing plot lines in film classes to showing students different types of non-written sources and allowing them to experience the difficulty of working with primary sources in history classes. The application also allows students to collectively work on a single source, upload all of their annotations into one place, and interact with each other’s thoughts and ideas.

Alongside their use in the classroom, such platforms permit collaborative work by libraries and archives. One of Dr. Clement’s goals is for libraries and digital archives to incorporate the collaborative ability of AudiAnnotate into their work. Imagine that, instead of relying on a few interns or workers to transcribe audio materials, archives used AudiAnnotate to allow scholars, researchers, and other interested parties to transcribe their sources. This is not a new idea; with projects like Citizen Archivist at the National Archives or Project PHaEDRA at the Smithsonian, crowdsourcing transcriptions can save institutions money and attract attention to their holdings. For all the internal pressure to digitize sources, combined with the external pressure from researchers who want access to digitized sources, AudiAnnotate serves as a cost-effective and collaborative way to answer the call to make sources more accessible.

While filling a void within the accessibility of archives and sources, AudiAnnotate not only allows scholars a more meaningful interaction with sources but also gives students and archives the ability to collaborate in new and innovative ways on audio sources that would otherwise be stored away in the “back storage room” of the digital archive. By giving researchers an easier means of engaging with audio material, Clement and her team give all the “lost” audio material a chance to be retrieved, transcribed, used, and preserved for future generations.

Dr. Tanya Clement is an Associate Professor in the English Department and the Director of the Initiative for Digital Humanities at the University of Texas at Austin. These applications are products of the High-Performance Sound Technologies for Access and Scholarship (HiPSTAS), where Clement is the principal investigator (PI) and has been supported variously by National Endowment for the Humanities grants, an Institute for Museum and Library Services grant, a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) grant, an American Council of Learned Societies Digital Extension grant, and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

[1] “In August 2010, the Council on Library and Information Resources and the Library of Congress issued a report titled The State of Recorded Sound Preservation in the United States: A National Legacy at Risk in the Digital Age. This report suggests that if scholars and students do not use sound archives, our cultural heritage institutions will not preserve them. “About,” High-Performance Sound Technologies for Access and Scholarship, accessed 13 December 2023, https://hipstas.org/about/.

Alyssa Peterson is the current IHS Graduate Research Assistant and a PhD Candidate in the History department. Her work focuses on the history of science, medicine, and the environment in the early modern British-Atlantic world. Her dissertation examines how British chemists and physicians used earthquakes and other natural disasters happening in Jamaica, North America, and England to better understand the composition of air over the long eighteenth century.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.