By Edward Shore

The Digital Public Libraries of America (DPLA) has published sets of primary sources to help students sharpen analytical skills, to empower educators to breathe life into history in their classrooms, and to enlighten anyone anywhere interested in history. The anthology focuses primarily on U.S history from the colonial era to the present. It compiles rare photographs, oral histories, political propaganda, speeches, advertisements, and other primary sources to tell sixty different stories. Themes range from the familiar— the “Exploration of the Americas” and the “Secession of the Southern States” — to the understudied— “Women and the Blues” and “American Indian Boarding Schools.” Each category contains between ten and twelve primary source materials. They humanize historical actors, contextualize major events, and “make real” the seemingly arcane and distant past. The public historians among us can use DPLA primary source sets to lend historical perspectives to contemporary debates.

Take, for instance, the uproar that has followed Beyoncé Knowles-Carter’s halftime performance at Super Bowl 50 in Santa Clara, California. Critics lashed out at Beyoncé and her dancers for wearing Black Panther-inspired costumes and carrying signs demanding justice for Mario Woods. Woods, 26, who was shot dead by San Francisco police officers on December 2, 2015, after he was suspected of stabbing a pedestrian. “I thought it was really outrageous that she used it as a platform to attack police officers,” Rudy Giuliani, the former mayor of New York City, told Fox and Friends. “These are the people who protect her and protect us and keep us alive.” “I’m tired of #BlackLivesMatter,” added Patrick Hampton, an urban youth minister from New York. “I’m tired of the New Black Panthers. I’m tired of seeing women on TV twerking. I’m tired of the racial division.”

Sadly, DPLA primary source sets do not elaborate upon the historical significance of twerking. But they can offer clues to explain why Beyoncé and her dancers paid tribute to the Black Panthers and #BlackLivesMatter during the Super Bowl.

Let’s start with the DPLA primary source set related to the “Black Power Movement.” The collection contains sermons, photographs, drawings, FBI investigations, and manifestos to shed light on the political and social movement whose advocates believed in racial pride, self-determination, and equality for all afro-descendant peoples. A sketch of a black man and woman captures an aesthetic that Beyoncé clearly sought to emulate: afro hair-dos, sleeveless blouse, a t-shirt with a raised black fist. That style was closely associated with the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, which originated in Oakland, California, some fifty miles away from Levi’s Stadium.

The Black Panthers’ 1966 party platform called for “an immediate end to police brutality and murder of black people.” We can surmise that Beyoncé’s tribute to the Black Panther Party was an expression of solidarity with the Bay Area African-American community after another fatal police shooting. According to the Guardian, the number of people killed by US police in 2015 reached 1,000 after Oakland police officers shot dead a man who allegedly pointed a replica gun at them. It was the 183rd such death recorded in California, by far the highest of any state. What better place to publicize police violence than the Super Bowl, the nation’s most popular television event where approximately 70% of athletes on the field were black?

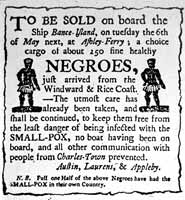

The public historian can synthesize materials from several DPLA primary source sets to tell a larger story about race relations in the United States. For instance, the Transatlantic Slave Trade collection offers the historical context for Beyoncé’s message of protest. I came across an advertisement for a slave auction in Charleston, South Carolina. “To be sold on board the ship the 6th of May next!” the caption reads. “A choice cargo of about 250 fine healthy NEGROES! The utmost care has been taken, and shall be continued, to keep them free from the danger of being infected with small pox onboard!”

This disturbing image underscores the callous normalization of violence against black bodies. It also helps to explain why it was so critical for Black Power activists to foster black pride and reclaim human dignity through the articulation of a bold, uncompromising Afrocentric message and aesthetic. (If you are curious about what smallpox looks like, you can consult the “Exploration of the Americas” collection. It contains a 1910 photograph of a man infected with variola, better known as smallpox.)

Finally, let’s respond to criticism that black activists have fostered “racial division.” DPLA primary source materials on the secession of southern states include an 1861 pamphlet, “The Causes which Impel the State of Texas to Secede from the Federal Union,” that highlights the origins of such divisions in the ways state governments codified racial apartheid into law. “We hold, as undeniable truths, that the government of the various states and of the Confederacy itself, were established exclusively by the white race, for themselves and for their posterity,” the manifesto proclaimed. “That negroes were rightfully held and regarded as an inferior and dependent race, and in that condition only could their existence in this country be rendered beneficial or tolerable.”

If any one group was most to blame for the promotion of “racial division” it was southern legislators. One should not need to remind Rudy Giuliani and Patrick Hampton that state-sanctioned apartheid persisted in states like Texas a full century after the conclusion of the Civil War. The legacies of secession and Jim Crown still loom large today. On January 8, 2016, Texas Governor Greg Abbott called for a Constitutional Convention to restore states’ rights. DPLA source sets reveal the extent to which white supremacists invoked “states’ rights” to defend slavery and segregation. Meanwhile, four in ten Trump voters in South Carolina wished the Confederacy had won the Civil War. Racial division persists in the United States. DPLA primary source sets such as “The Secession of the Southern States” illuminate its historical, structural foundations.

DPLA primary sources may not win hearts and minds at Fox News. Still, they can help anyone acquire a richer account of the Black Power Movement than Texas SBOE-sanctioned text books. The collection possesses several shortcomings. Although it furnishes educators with ample documentation to challenge those who reduce the Black Panther Party to “thugs,” DPLA primary source sets do little to explain why critics have associated the movement with violence in the first place. It also fails to highlight women’s voices within the Black Power Movement. Where are selections from Assata Shakur’s autobiography? Why not include excerpts from Angela Davis’s memoirs? These and other sources can give necessary and even richer background to contextualize Beyoncé’s performance and its historical implications.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.