By Steven Mintz

Why is knowledge of the history of childhood valuable?

First, because history defamiliarizes the present, reminding us that concepts, practices, and ideas that we take for granted are in fact problematic. Take, for example, the Freudian notion that early childhood determines a child’s future development, shapes their personality, and leaves a lasting imprint on their future relationships. Few thinkers would have accepted these ideas prior to the twentieth century. Thus in his 1749 novel The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling, Henry Fielding dismissed the title character’s childhood in six words: “nothing happened worthy of being recorded.”

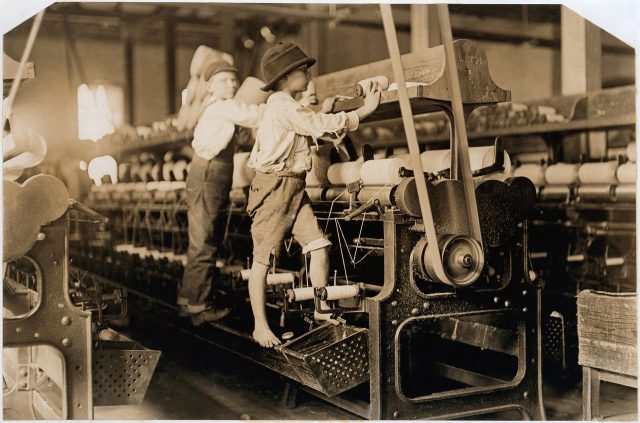

Or take the assumption that very young children are incapable of performing sophisticated chores. In most past societies, children took on work responsibilities from extremely young ages, often as young as two or three. Abraham Lincoln, for example, assisted his father in clearing fields when the future president was only two years old.

Mill children in Macon, Georgia in 1909 (Photo by Lewis Hine via Wikipedia).

Or the view popularized by attachment theorists that proper child development requires secure attachment to a single mothering figure and a stable household environment. In fact, many, and perhaps most, children in the past had multiple nurturing figures and shifted frequently among households.

Or, more controversially, consider the current medical advice that co-sleeping arrangements, where a mother and her infant share the same bed, puts the child at risk. From a historical perspective, it was highly unusual for mothers and infants to sleep apart, and even in the United States, reliance on cribs is a relatively recent development, dating to the early twentieth century. Separate sleeping arrangements for infants appears to reflect this society’s emphasis on cultivating individualism from a very early age.

Then, too, history rebuts myths and misconceptions that distort public understanding. For example, take the myth of the carefree childhood. We cling to a fantasy that once upon a time childhood and youth were years of carefree adventure, despite the fact that for most children in the past, growing up was anything but easy. Disease, family disruption, and early entry into the world of work were integral parts of family life into the early twentieth century. The notion of a prolonged childhood, devoted to education and free from adult-like responsibilities, is a very recent invention, a product of the past century and a half, and one that only became a reality for a majority of children after World War II.

Margaret Gibson (far right) described a happy and carefree childhood in her middle-class home in Scotland. This photo was taken in 1932, two months before she died of scarlet fever (via Portal to the Past).

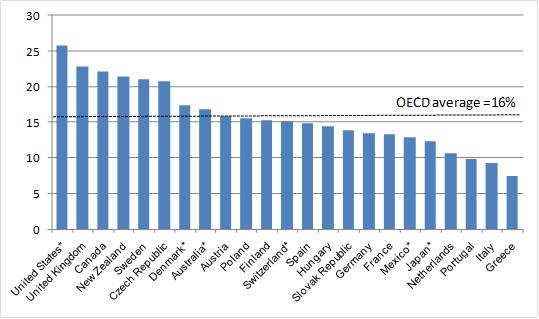

Another myth is the home as a haven and bastion of stability in an ever-changing world. Throughout American history, family stability has been the exception, not the norm. At the beginning of the twentieth century, fully a third of all American children spent at least a portion of their childhood in a single-parent home, and as recently as 1940, one child in ten did not live with either parent—compared to one in 25 today.

Percentage of Children 0-14 living in single-parent households in 2010 (via The Atlantic).

A third myth is that childhood is the same for all children, a status transcending class, ethnicity, and gender. In fact, every aspect of childhood is shaped by class—as well as by ethnicity, gender, geography, religion, and historical era. We may think of childhood as a biological phenomenon, but it is better understood as a life stage whose contours are shaped by a particular time and place. Childrearing practices, schooling, and the age at which young people leave home—all are the products of particular social and cultural circumstances.

[jwplayer player=”2″ mediaid=”12386″]

A fourth myth is that the United States is a peculiarly child-friendly society when, in actuality, Americans are deeply ambivalent about children. Adults envy young people their youth, vitality, and physical attractiveness. But they also resent children’s intrusions on their time and resources and frequently fear their passions and drives. Many reforms that nominally have been designed to protect and assist the young were also instituted to insulate adults from children and insure smooth operation of the economic order.

Lastly a myth, which is perhaps the most difficult to overcome, is a myth of progress, and its inverse, a myth of decline. There is a tendency to conceive of the history of childhood as a story of steps forward over time: of parental engagement replacing emotional distance, of kindness and leniency supplanting strict and stern punishment, of scientific enlightenment superseding superstition and misguided moralism. This progressivism is sometimes seen in reverse, i.e. that childhood is disappearing: that children are growing up too quickly and wildly and losing their innocence, playfulness, and malleability. Both the myth of progress and the myth of decline are profoundly misleading. Historical change invariably involves trade-offs; all progress is achieved at a price and involves losses as well as gains. We are certainly the beneficiaries of dramatic declines in rates of infant and child mortality and increased control over childhood diseases. But it is also apparently the case that more children than ever suffer from disabilities and chronic conditions than in the past.

History also refutes any simplistic linear theories about upward and onward progress and any assumptions about inevitability. One striking example involves child abuse. Although the physical and sexual abuse of children appears to have declined in recent years, other forms of abuse remain prevalent. These include the violence of expectations – the assumption that children are able to achieve certain markers of maturity before previous eras deemed them physiologically or psychologically ready; the violence of labeling – of attaching pathological labels upon normal childish behavior; the violence of representation – the sexual exploitation of images of girls in advertising; and the violence of poverty, which exposes children to extraordinary stressors and limits their future possibilities.

Children doing yoga in New York City to reduce school-related stress (Via DNAinfo New York).

In addition, history lays bare certain long-term trends, developments, and processes that we are otherwise blind to. Examples include the long-term shift from an environment in which children were expected to love their parents to one where parents seek to earn their children’s love; or the triumph of a therapeutic discourse, which uses psychological categories to understand children’s behavior and focuses on children’s emotional interior.

History also offers valuable lessons: That even very young children are more competent than our society assumes or that ideas about the nature of the child or how best to rear children have always been hotly contested.

Perhaps most important of all, history offers a fresh perspective on life today. It allows us to view present-day concerns and controversies from a novel vantage point. History offers dynamic, diachronic, longitudinal perspectives that are quite different from those generally advanced by the disciplines of psychology or sociology. By treating concepts and behavior patterns as constructs, history underscores the radical contingency of all social arrangements and modes of thought. In addition to stressing the importance of change over time, history also emphasizes the significance of social and cultural context, which has been always been crucial in shaping the nature and timing of key life course developments, indeed, more important, in my view, than any innate states of psychological or physiological development. History reminds us that conceptions of childhood and children’s essential nature, theories of child development, and approaches to childrearing – all have shifted profoundly over time.

The history of childhood is of more than antiquarian interest. Too often, history is regarded as preface – that is, as a source of fascinating anecdotes – or as mirror – a stark contrast to our supposedly more enlightened present. But history, including the history of childhood, is of more than antiquarian interest. With its emphasis on four C’s – change over time, the significance of context, the role of contingency in shaping historical development (and rejection of teleology), and the ever-present reality of conflict – greatly enriches, and, at times, challenges, the insights gleaned from other social sciences.

Steven Mintz, Huck’s Raft:A History of American Childhood (2006) and The Prime of Life: A History of Modern Adulthood (2015)

Want to read more about childhood? Here are Steven Mintz’s picks for further reading.