![“En las urgencias de la realidad [Within the urgencies of reality]:” Perspectives about the Vicaría de la Solidaridad](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Lozano-Long-Conference-1-1.png)

by Lucy Quezada Yáñez [1]

In honor of the centennial of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, the 2022 Lozano Long Conference focuses on archives with Latin American perspectives in order to better visualize the ethical and political implications of archival practices globally. The conference was held in February 2022 and the videos of all the presentation will be available soon. Thinking archivally in a time of COVID-19 has also given us an unexpected opportunity to re-imagine the international academic conference. This Not Even Past publication joins those by other graduate students at the University of Texas at Austin. The series as a whole is designed to engage with the work of individual speakers as well as to present valuable resources that will supplement the conference’s recorded presentations. This new conference model, which will make online resources freely and permanently available, seeks to reach audiences beyond conference attendees in the hopes of decolonizing and democratizing access to the production of knowledge. The conference recordings and connected articles can be found here.

En el marco del homenaje al centenario de la Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, la Conferencia Lozano Long 2022 propició un espacio de reflexión sobre archivos latinoamericanos desde un pensamiento latinoamericano con el propósito de entender y conocer las contribuciones de la región a las prácticas archivísticas globales, así como las responsabilidades éticas y políticas que esto implica. Pensar en términos de archivística en tiempos de COVID-19 también nos brindó la imprevista oportunidad de re-imaginar la forma en la que se llevan a cabo conferencias académicas internacionales. Como parte de esta propuesta, esta publicación de Not Even Past se junta a las otras de la serie escritas por estudiantes de posgrado en la Universidad de Texas en Austin. En ellas los estudiantes resaltan el trabajo de las y los panelistas invitados a la conferencia con el objetivo de socializar el material y así descolonizar y democratizar el acceso a la producción de conocimiento. La conferencia tuvo lugar en febrero de 2022 pero todas las presentaciones, así como las grabaciones de los paneles están archivados en YouTube de forma permanente y pronto estarán disponibles las traducciones al inglés y español respectivamente. Las grabaciones de la conferencia y los artículos relacionados se pueden encontrar aquí.

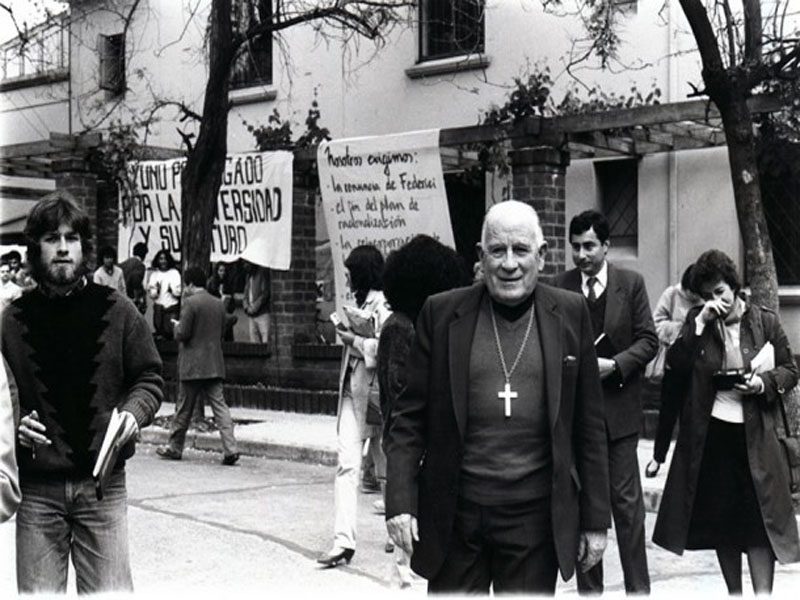

The Vicaría de la Solidaridad was constituted as an archive in 1992. It emerged in the wake of the cruelest dictatorship that afflicted Chile under the right-wing authoritarian military rule of Augusto Pinochet from 1973-1990. But, the Vicaría had earlier origins in the “Comité de Cooperación por la Paz en Chile.” This ecumenical institution was formed in response to the turbulent climate of the first days of the civil-military dictatorship in 1973, as several civil society sectors considered that organizing was the proper and most urgent action to take. Members of the Comité organized not only to search for justice in favor of those detained, tortured, killed, and forcedly disappeared, but also for groups living in poverty on the periphery of Santiago. Since their formation, however, the Comité received several attacks and direct threats from the dictatorship. The Catholic Church—through the Cardenal Raúl Silva Henríquez—decided to create the Vicaría de la Solidaridad. As an institution directly dependent on the Catholic Church, the Vicaría gained greater scope for action and more protection against the State. However, working inside the Vicaría never was totally safe.

In 1992, when the Vicaría consolidated as an archive, its team started to take care of materials that are a key part of the unbearably tragic memories of many families and one of the most traumatic chapters in Chilean history. The Vicaría has compiled and preserved the documents that registered the violation of human rights and the crimes against humanity committed by the civil-military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990). Their mission is to use these documents to grant legal and social support to the victims and their families. The actions registered by this archive come from an array of different sources including testimonies and declarations, lists of disappeared people, press clips related to crimes, photographs, and many other types of sources. The transformation of the Vicaría into an archive was organic and responded to the urgent need to document the worst years of the dictatorship, characterized by State terror and an increase of poverty and inequality.

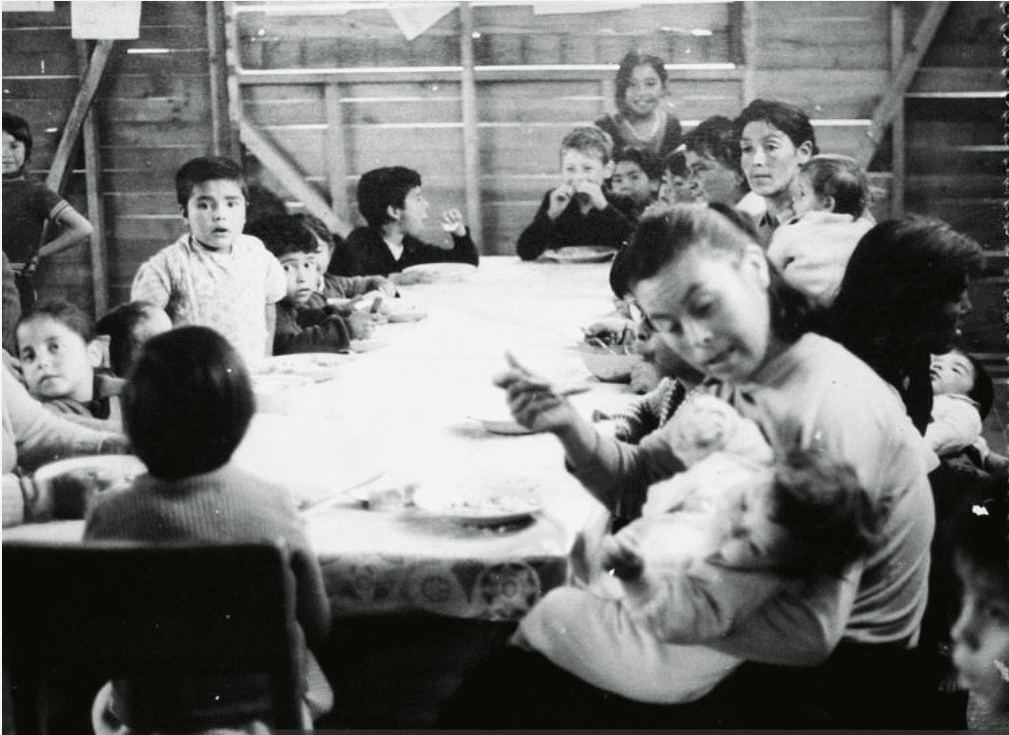

The climate of violence was not only coming from state terrorism but also from high rates of unemployment and poverty. This is a topic mostly erased of Chilean historiography, but it challenges the false idea that the dictatorial government gave Chile economic stability and prosperity. On the contrary, the first years of the dictatorship were the hardest in economic terms, and the role of socioeconomic support played by the Comité de Cooperación por la Paz (later becoming the Vicaría) was crucial for so many people occupying the peripheral zones of Santiago. One example of this support was the commission specially dedicated to the unemployed for political reasons. In addition, people were able to receive funds from the different international agencies sending monetary aid to Chile, administered by the Comité.[2]

Economic hardship caused unrest, and the Chilean dictatorship sought to violently repress unrest through disappearances and torture, causing the eradication of entire communities after the coup d’état of September 11th of 1973. Chilean women affiliated with the Vicaría challenged these efforts. Many women inside the Vicaría were protagonists in reconstructing the political and affective relationships systematically erased by State terrorism. Women were the ones reestablishing the social fabric that enforced disappearance and torture tried to erase. The continuous existence of the Vicaría and its archive shows us how important community organization is in violent times. In a climate where death and pain reigned, the committed resistance through collective organization means taking the side of life and memory.

As a Chilean and a Latin-American art historian, I focus my research on the visual arts produced during the region’s civil-military dictatorships between the 1960s and 1980s. Indeed, my primary focus is Chile because I was born and raised there. I still can remember the first time I encountered the Vicaría as a researcher. I was young, and the Vicaría was already on my radar as a key institution that has become part of the popular and collective memory of the country – especially after the release of the TV series “Los Archivos del Cardenal.”[3] At that time, I had the task of identifying the most precise number of victims of state terrorism during the dictatorship. Up to now, this is a matter of debate inside the field of Chilean history. Several institutions have come up with numbers, all of them debatable since the Chilean state has not declassified all the documentation regarding that period. I ended up navigating the Vicaría archive, reading letters from painter José Balmes and other artists, living in exile but having the Vicaría as a bridge to help people impacted by the dictatorship. This experience gave me the chance to understand from my specific field the relevance of the Vicaría and think about the necessity of dialogue between holding archives of materials related to this period. From the field of art history and visual arts, I encourage humanists to create dialogues with institutions like the Vicaría, especially considering that beyond the legal documentation they preserve, there are other genres of documents – donated artworks, letters, press clippings, and photographs that are waiting to be studied from new interdisciplinary perspectives.

In Chile, we are again suffering state terrorism and impunity in the current times after the social revolt of October of 2019. How we deal with our traumatic memory and the pain inflicted by the state is still a very present and vital matter. In this context in which present crises manifest in front of us, the interactions and dialogues with our historical memory and its archives are crucial. They are an opportunity to learn that resistance, organization, documentation, and preservation become fundamental to insist and persist in taking the side of life and never allow the repetition of those terrible times.

María Paz Vergara, representative from the Fundación de Documentación y Archivo de la Vicaría de la Solidaridad participated in the panel “(Re)conociendo community rights through archives and memory” at the 2022 Lozano Long Conference. This discussion explored the pursuing and claiming of rights by several communities gathering historical records. The conference was held in a hybrid format, allowing participants to attend regardless of their location.

Lucy Quezada is a Chilean doctoral student in the Center for Latin American Visual Studies (CLAVIS) at The University of Texas at Austin, sponsored by ANID and The Fulbright Program. Her research explores the official field of visual arts during the military dictatorships of Argentina, Brazil, and Chile between the 1960s and the 1980s. Her previous research projects focused on cultural institutions from the early 1970s in Chile, such as the Museo de la Solidaridad and the Instituto de Arte Latinoamericano. Currently, she is the Mellon Fellow in Latin American art at the Blanton Museum of Art.

[1] The title phrase is extracted from Vicaria de la solidaridad: Historia de su trabajo social. Santiago de Chile: Paulinas, 1991. The complete sentence said: “Si bien no existía un proyecto de trabajo pre-establecido, había una reflexión en torno a las urgencias de la realidad, que daría muchas luces para abrir el camino.” [“Although no pre-established project existed, there was a need to reflect on the urgencies of reality, which would grant lights to open the way” (p. 11)

[2] Later, this commission separated from the Comité and was transformed into an autonomous organization, called COMSODE, Comisión de Solidaridad y Desarrollo (Commission of Solidarity and Development).

[3] Chilean TV series based on the history of the Vicaría de la Solidaridad, released in 2011 by Televisión Nacional de Chile.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.