In the series finale of Mad Men, Don Draper (Jon Hamm) finds himself at a California retreat center overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Over the course of several days, Draper attends seminars where participants talk about what’s bothering them. At first, he’s skeptical of the place, reluctantly engaging with other people to support the niece who wanted to attend the retreat. When she leaves him, with no car and no escape, Draper is forced to find peace with himself. In the final scene, he participates in a morning meditation session. He sits with his legs crossed and his eyes closed. Upon uttering an “om,” a bell rings, as Draper has yet another advertising epiphany, and the show ends with the famous “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke” commercial. Draper finally accepted that he was an ad man, albeit one who was responding to — and incorporating elements of — changing social and cultural norms.

In Encountering America: Humanistic Psychology, Sixties Culture, and the Shaping of the Modern Self, Jessica Grogan examines the rise, demise, and lasting impact of humanistic psychology, a mental health movement that sometimes incorporated meditation, always emphasized self-acceptance, and that Grogan implies changed the corporate world for the better. Grogan offers detailed and illuminating portraits of the individuals most responsible for shaping humanistic psychology — Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, and Rollo May — while putting their movement in historical context. As Grogan demonstrates, humanistic psychology emerged in the 1950s and grew in the 1960s because Maslow, Rogers, May, and others thought psychology had lost its way. In the early Cold War, professional psychologists focused on individuals’ pathologies and academic psychologists emphasized empirical studies at the expense of theory and philosophy. Humanistic psychology, with its emphasis on personal growth and the practice of nondirective therapy, challenged the status quo. By the 1970s, Grogan believes, humanistic psychology infiltrated various segments of American intellectual, cultural, and social life, laying the foundations for today’s therapy culture.

Grogan’s well-constructed and easy-to-follow narrative highlights the discontent that existed in the 1950s and 1960s and the ways that humanistic psychologists offered Americans a new kind of therapy. The threat of nuclear war, not to mention excessive conformity, were key factors for a despondent national mood. Grogan shows that humanistic psychologists had the same critiques of American culture put forth in David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd (1950) and Sloan Wilson’s The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit (1956). And she traces the solution humanistic psychologists pursued: create, develop, refine, and advertise a subfield of psychology that emphasized personal growth and individualism.

Grogan’s well-constructed and easy-to-follow narrative highlights the discontent that existed in the 1950s and 1960s and the ways that humanistic psychologists offered Americans a new kind of therapy. The threat of nuclear war, not to mention excessive conformity, were key factors for a despondent national mood. Grogan shows that humanistic psychologists had the same critiques of American culture put forth in David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd (1950) and Sloan Wilson’s The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit (1956). And she traces the solution humanistic psychologists pursued: create, develop, refine, and advertise a subfield of psychology that emphasized personal growth and individualism.

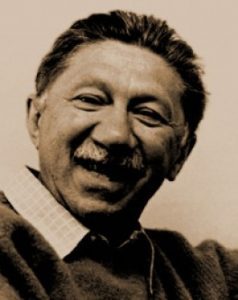

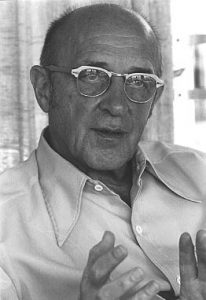

Humanistic psychologists had a formidable challenge ahead of them. For nearly fifty years, Freudian psychoanalysts and empirical behaviorists dominated the practice of psychotherapy. Grogan describes how Maslow, Rogers, May, and others aimed to transform psychology and American culture in spite of this longstanding dominance. Maslow, a professor of psychology at Brandeis, then a fledgling and financially struggling university, wrote theoretical and philosophical texts, mixed with some small-scale empirical studies, that emphasized the healthy parts of human development and personal growth. Rogers and May pushed humanistic psychology in other directions. Rogers, who taught at the University of Wisconsin at Madison and left to join the Western Behavioral Sciences Institute (WBSI) in La Jolla, California, in 1963, established person-centered therapy. According to Grogan, person-centered therapy allowed for a relationship to develop between psychologist and patient, thus questioning old models where a stifled psychoanalyst listened to her patient and then asked probing questions. May, on the other hand, pushed for group therapy, challenging the predominant belief that therapy had to be a one-on-one relationship between psychoanalyst and patient.

By the end of the 1960s, humanistic psychology had gained repute in disparate areas of American intellectual, cultural, and social life. Grogan demonstrates that Maslow, Rogers, and May were able to carve out a space within the psychological discipline for humanistic psychology, organizing their own journals and conferences. Rogers’ ideas about person-centered therapy also dramatically changed the fields of social work and education, putting increasing emphasis on the lived (and subjective) experiences of clients and students. And at least initially, humanistic psychologists supported Timothy Leary’s ideas about the therapeutic uses of LSD. In addition, Grogan examines California’s Esalen Institute, the place that many commentators believe Don Draper found himself in the last episode of Mad Men. Esalen practiced encounter-group therapy and meditation and spiritual practices as paths to self-actualization. By covering such an array of people and places, Grogan underscores that humanistic psychology found a diverse group of followers in the 1960s and 1970s.

Encountering America is a fascinating work of cultural and intellectual history. It would have been easy for any historian to get bogged down in the details about the many people, ideas, and events related to humanistic psychology, but Grogan’s narrative style keeps the reader interested. Grogan’s least developed point, however, deals with humanistic psychology’s connections to corporate America. It is clear that humanistic psychology had some impact on the business world (for example, companies now offer employee retreats and sensitivity training), but at what cost? Was this a dramatic victory for humanistic psychology? Or was it selling out? Grogan implies that the changes were for the best, but she also hints that humanistic psychology could only do so much to change businesses’ adherence to the profit-motive. Importantly, Grogan has written a work that could help future historians probe these questions. Anyone interested in Sixties culture and/or the history of psychology should find themselves immersed in this work.

Jessica Grogan, Encountering America: Humanistic Psychology, Sixties Culture, and the Shaping of the Modern Self (Harper Perennial, 2012)

You may also like:

Christopher Babits on Age of Fracture, by Daniel T. Rodgers (2011)

Jing Zhai explains Jacques Derrida and Deconstruction

Adrian Masters recommends Freud’s Mexico: Into the Wilds of Psychoanalysis by Rubén Gallo (2010)