By Travis Gray

Shelia Fitzpatrick’s work provides a detailed exploration of daily urban life in Stalinist Russia. Covering a wide array of subjects, including bureaucracy, consumption, utopianism, family life, and the Great Purge, she argues that “Stalin’s Revolution” forced ordinary Russians to adopt new attitudes and practices that ensured survival in the face of scarcity and repression. Fitzpatrick presents three major arguments to support this claim. First, chronic shortages in housing and consumer products generated alternative strategies for acquiring scarce goods. Second, the state’s obsession with social origin and status prompted marginalized people (e.g. priests, kulaks, and political prisoners) to conceal their past identities in order to rejoin Soviet society. Third, state surveillance taught Soviet citizens to distrust Soviet officials creating an environment of mutual suspicion that resulted in the mass terror of 1937-38. Overall, Fitzpatrick’s arguments are persuasive and compelling, presenting a complex portrait of Stalinism through the daily experiences of those who lived it.

Shelia Fitzpatrick’s work provides a detailed exploration of daily urban life in Stalinist Russia. Covering a wide array of subjects, including bureaucracy, consumption, utopianism, family life, and the Great Purge, she argues that “Stalin’s Revolution” forced ordinary Russians to adopt new attitudes and practices that ensured survival in the face of scarcity and repression. Fitzpatrick presents three major arguments to support this claim. First, chronic shortages in housing and consumer products generated alternative strategies for acquiring scarce goods. Second, the state’s obsession with social origin and status prompted marginalized people (e.g. priests, kulaks, and political prisoners) to conceal their past identities in order to rejoin Soviet society. Third, state surveillance taught Soviet citizens to distrust Soviet officials creating an environment of mutual suspicion that resulted in the mass terror of 1937-38. Overall, Fitzpatrick’s arguments are persuasive and compelling, presenting a complex portrait of Stalinism through the daily experiences of those who lived it.

Consumption is a major theme in this work. Fitzpatrick emphasizes the ubiquity of shortages and how this led to a national obsession with obtaining and hoarding consumer goods. Indeed, survival often depended on an individual’s ability to undermine the state’s centralized distribution system through speculation and blat (reciprocal relationships involving goods and favors). These two elements constituted a “second economy” and was, according to Fitzpatrick, the most important aspect of urban life in Stalinist Russia. The second economy not only “took the edge off the harsh circumstances of Soviet life,” but also revealed that the state was a flexible entity that could be subverted and negotiated with on a daily basis (65).

Fitzpatrick goes on to discuss the rigid social hierarchies that characterized Soviet society. Indeed, the regime’s elite bore the marks of aristocratic privilege (e.g. champagne, caviar, private cars, and dachas) and used their connections with the Soviet state to rise to the top of the social ladder. Fitzpatrick’s most important contribution, however, is her detailed description of marginalized social groups. In order to survive, many of these people tried to conceal their identities by creating “two personae, an ‘invented’ public self and a ‘real’ private self” (132). Although many were later unmasked by the state, these instances illustrate the great risks that ordinary people were willing to take in order to reincorporate themselves into Soviet society.

Children are digging up frozen potatoes in the field of a collectivefarm. Udachne village, Donec’k oblast 1933

Finally, the last two chapters of this work deal with the nature of state surveillance as well as the Great Purge of 1937-38. Although these subjects have been covered before by a number of different authors, Fitzpatrick approaches these two subjects in a radically different way. Surveillance in Stalinist Russia was multi-directional, the state was not only watching its citizens, but its citizen’s were also watching the state. These mutual feelings of distrust and suspicion prompted a wave of denunciations and arrests that led to the Great Purge. As a result, the Great Purge was characterized by widespread popular support among citizens who resented state officials and the privileged urban elite. By preemptively denouncing these “enemies of the people,” individuals sought to ensure their own safety as well as rid themselves of their personal enemies.

NKVD chiefs responsible for conducting mass repressions: Yakov Agranov, Genrikh Yagoda, Stanislav Redens. 1934.

In sum, this book provides the reader with deep insight into the nature of Stalinism as a day-to-day experience. It helps characterize daily urban life within the Soviet Union as a constant struggle for survival amidst shortages, repression, and terror.

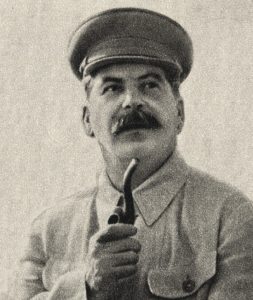

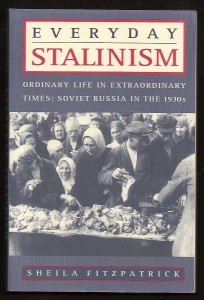

Sheila Fitzpatrick, Everyday Stalinism. Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times: Soviet Russia in the 1930s (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000)

You may also like:

Veterans Memorial High School Orwellian approach to the horrors of Joseph Stalin

Travis Gray reviews Stalin’s Genocides by Norman Naimark (2011)

Andrew Straw discusses The Unknown Gulag: The Lost World of Stalin’s Special Settlements by Lynne Viola (2007)