Commentators and scholars have long represented the United States as the supreme guarantor of a well-tempered international order. Today, however, agents of American international relations find themselves confronting uncertainty both at home and abroad. Nevertheless, as they navigate the uncharted waters of contemporary global politics, representatives of the United States and its international interlocutors can still look to their shared past for insight. There are lessons, some positive, some deeply negative, to be learned in the long, complex, and decidedly messy history of the United States in the world.

Produced in collaboration with the Clements Center for National Security, Not Even Past‘s “Uncharted Waters” series is bringing that history to life in detailed case studies, highlighting moments when Americans have grappled with the uncertainties of power. Our aim is to document unease and confusion, hidden dangers and unexpected opportunities. In so doing, we will provide readers with a fresh and provocative perspective on the history of American foreign relations.

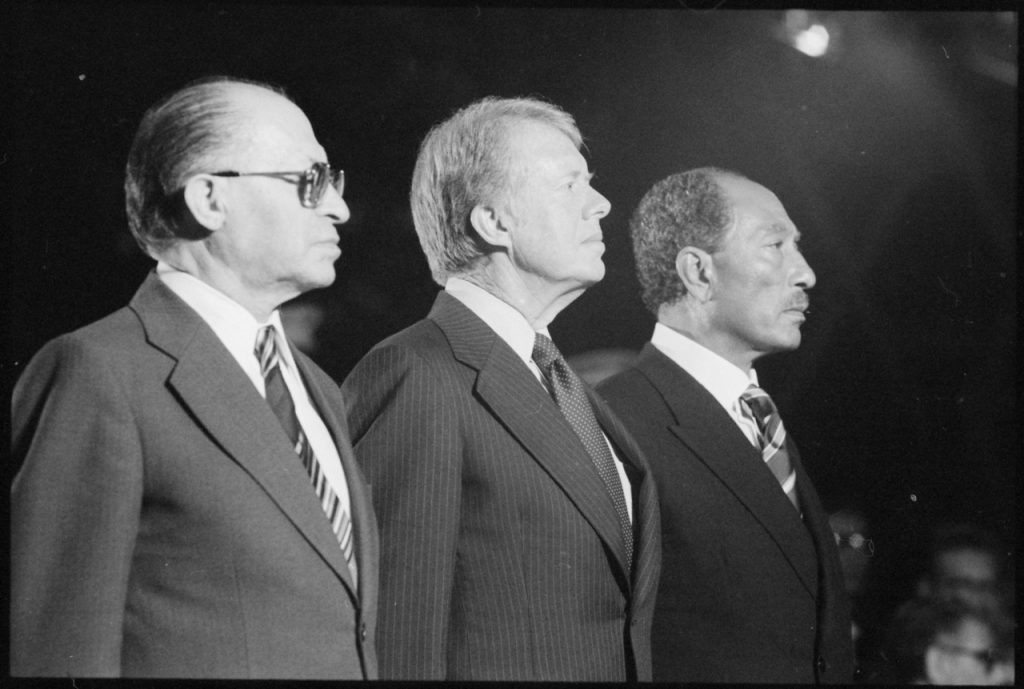

Concluded on September 17th, 1978, the Camp David Accords between Egypt, Israel, and the United States were a landmark achievement in the history of American diplomacy, representing a crucial step toward potentially ending the long-running Arab-Israeli conflict. While not a formal treaty, the Accords included two frameworks: one for bilateral Egyptian-Israeli peace, the other for settling the question of Palestinian sovereignty.

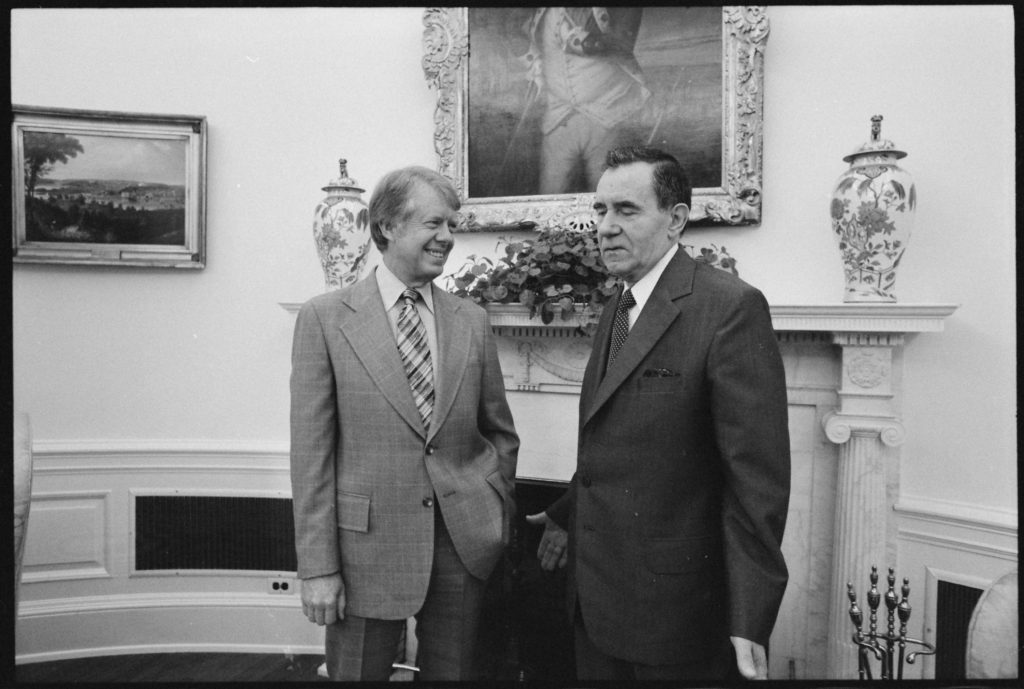

Less than two months later, the Arab League Summit at Baghdad (November 2nd–5th, 1978) rejected the Camp David Accords and established a set of punitive measures to be implemented if Egypt and Israel agreed to a formal treaty. This stunned and infuriated American President Jimmy Carter, who had counted on the Saudis to block such an action. Soviet leaders, by contrast, were delighted with the result.

In the month and a half between the signing of the Camp David Accords and their rejection at Baghdad, the United States, the Soviet Union, and Arab actors engaged in a flurry of activity ranging from public diplomacy to secret plots to “kidnapping,” as each sought to advance their interests. Archival documents and memoirs from Soviet, American, and Arab participants reveal this hitherto-obscured history, documenting the intricacies of a frenetic and crucial period.

Ultimately, Arab backlash against the Accords gave the Soviets a golden opportunity to push their advantage in an attempt to reassert their importance in the Middle East and show that they, as the United States’ rival superpower, also had to be consulted in matters of international and regional significance. It also underscored the fragility of the peace process and threatened American dominance in the region, while highlighting a major area of Soviet-American tension, one that would significantly contribute to renewed superpower competition with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan just over a year later. Finally, the moderate Arabs’ decision not to cooperate with the United States—despite its singular focus on gaining such cooperation, at the cost of any real U. S. policy toward the enemies of the peace process—makes this a story of how relatively weak states can create significant problems for powerful countries, a lesson the United States has failed to learn time and again.

Three Camps

The Arab-Israeli conflict dates back to 1948, when Jewish settlers displaced Palestinians to create the modern Israeli state. On the day of Israel’s founding, the surrounding Arab states attacked it, but were beaten back. In the decades since, the Arab-Israeli conflict saw several significant flareups, including the Suez Crisis of 1956, the Six-Day War of 1967, and the October War of 1973. In the wake of the October War, American Secretary of State Henry Kissinger negotiated ceasefire deals between Israel and Syria and initiated a bilateral peace process between Egypt and Israel which ultimately went nowhere.

By the time the Egyptian-Israeli peace talks resumed in the late 1970s, largely due to an initiative launched by Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat, the Middle East was split into three broad camps as far as the Arab-Israel peace process was concerned: the negotiating parties, the “rejectionists,” and the “moderates.” The negotiating parties were those states engaged directly in the peace talks; in this case, Egypt and Israel. They were pro-Western and generally cooperated with the United States, which sought to end the Arab-Israeli conflict, counter Arab “radicalism,” and prevent Soviet re-entry to the region.

The rejectionist Arabs, on the other hand, rebuffed negotiation with Israel and refused to even recognize it as a state. Rejectionists were politically “radical” states dominated by leftist regimes that were typically pro-Soviet. Indeed, in the Arab context, “radical” and “rejectionist” referred to the same states; as British officials noted in 1979, “many of the radicals would not exist but for the Arab/Israel dispute.”[1] American and even some Soviet policymakers referred to them as “radical/s.”[2] Rejectionism also drew on pan-Arabism, emphasizing the need for Arab unity across national borders.[3]

Most rejectionists were members of the Steadfastness and Confrontation Front, a multinational group that included Algeria, Libya, Syria, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY, or South Yemen); only one rejectionist state, Iraq, was not part of the Front. All of the rejectionists enjoyed Soviet backing, not because the USSR did not want peace in the Middle East, but because it wanted to be a full participant in the peace talks and reassert its importance in the region.[4] This was a natural response to its ouster from the Middle East, which had been orchestrated by the Nixon and Ford administrations.[5] The Soviets therefore saw the Camp David Accords as an opportunity to undermine American influence in the Middle East. Their rejection of the Accords, while unsurprising, stemmed not so much from any opposition to the contents themselves, but more from a desire to capitalize on Arab rejectionism, their frustration at having been excluded from the peace process, and their hostility to Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat, whose consistent antipathy toward the USSR was making him look like a pawn of the West.[6]

American policymakers, by contrast, saw Arab moderates, particularly Saudi Arabia and Jordan, as crucial to obtaining a comprehensive peace in the Middle East.The moderates were more open to the peace process, but had clear (albeit relatively limited) reservations stemming from their national interests and the ideological imperatives of pan-Arabism. Moderates were usually pro-Western in orientation or strove to maintain their non-aligned status, and feared Soviet influence and the Arab radicals who promoted it, not least because many moderate regimes were also monarchies, and therefore fundamentally opposed to the progressive and populist agendas of the radicals.

After the Camp David Accords were signed, the United States sought moderate acquiescence, if not approval of the agreement. President Carter tried to bring other Arabs into the peace process, via both direct negotiation and indirect approaches through influential European states like France and the United Kingdom.[7] By contrast, Egyptian president Anwar Sadat stuck to a unilateralist line, dismissing the other Arabs as unimportant. Sadat seemed far less concerned about what other Arab leaders thought—he regularly called them “dwarfs and pygmies”—and told Carter not to worry about their reactions, going so far as to publicly ridicule the Front and the Soviets.[8] Based on his earlier statements and the clear need for moderate support, however, it seems Sadat was exaggerating his confidence. Indeed, some Egyptian officials thought he was intentionally inflaming relations with other Arabs to keep them out of the negotiations. He would soon get his wish.[9]

“A Pilgrimage of Arabs to Moscow”: The Soviets Take Action

American diplomats initially assumed that the “radical” Arabs’ rejection of the Camp David Accords was a foregone conclusion.[10] As if to confirm their suspicions, the Soviets and their radical friends soon issued explicit public and private condemnations of the Accords.[11] At its Damascus Conference (September 20th–23rd, 1978), the Steadfastness and Confrontation Front condemned the Camp David Accords and declared that it would sever relations with Egypt, encourage subversive elements inside Egypt, and seek better relations with the Soviet Union, authorizing Syrian president Hafez al-Assad to represent the Front during his upcoming trip to Moscow.[12]

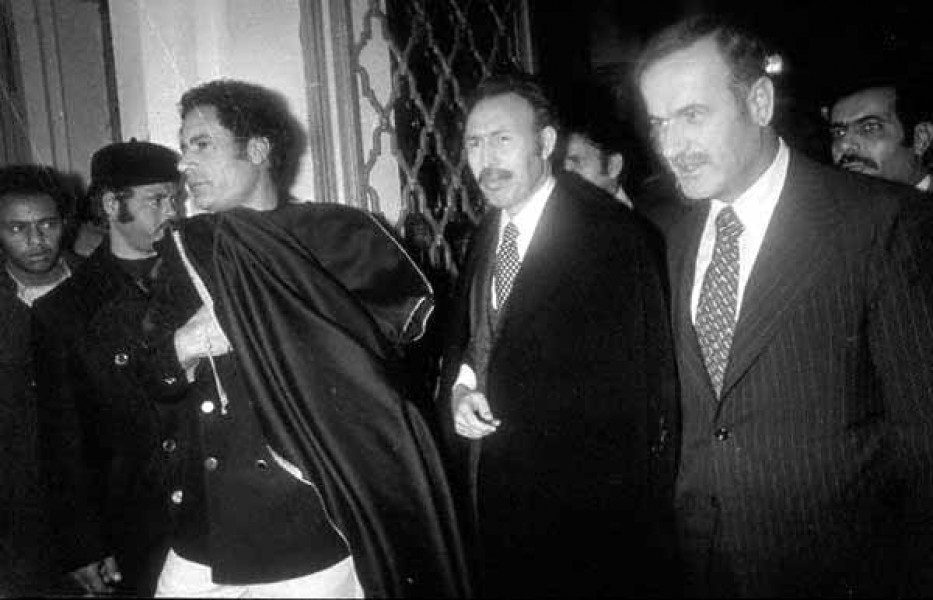

Despite the Front’s decision to strengthen its ties to the Soviets, it became apparent both before and during the conference that it was not a cohesive unit. Assad implied that Libyan dictator Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi had reneged on his duties under the Front’s founding document by failing to financially support to Palestinian groups.[13] The delegates also clashed over economic ties with Egypt, eventually deciding to implement sanctions. Some rejectionists pushed for anti-American measures, but Assad and Algerian president Houari Boumediene objected, hoping to maintain their nonaligned status. The Front also toned down its rhetoric toward the moderates in order to win them to its side.[14] Shortly after the Damascus Conference, the Front also met in Algiers, where a temporary Syrian-Libyan rapprochement encouraged Gaddafi to attempt an unusual diplomatic maneuver: the Libyan dictator “kidnapped” his nominal ally, Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, and forcibly transported him to Jordan in an attempt to improve the PLO’s relations with King Hussein, which had been sour for almost a decade. Gaddafi later explained that he took this dramatic step with the Front’s interests at heart.[15] Indeed, the Jordanian rapprochement with the PLO drastically improved the chances of a collective Arab stance against the Camp David Accords, as it helped heal—at least temporarily—a major rift within the Arab world.

The ebb and flow of Middle Eastern politics ultimately favored the Soviets—and weighed against the Camp David Accords. This was certainly true in the case of Syria. As President Assad attempted to balance the Front between the superpowers and maintain a moderate approach toward the peace process, he tilted in response to his anxieties about his country’s global and regional standing. At the time, Assad faced not only internal unrest but also the external challenges of navigating the Cold War, an unresolved conflict in neighboring Lebanon, and tensions with another neighbor, Iraq, as well as the peace process itself, which upset the local balance of power. Egypt had been crucial in helping Syria deal with the potential threat of war with against Israel. Egyptian-Israeli peace meant Israel could shift its military power to the Syrian border. Assad therefore chose to pursue closer relations with the Soviets, hoping improved ties would enable him to more effectively oppose the peace process.[16]

The Soviets were happy to oblige. “We need to do everything so that the heat of rejection of a separate deal between Egypt and Israel does not fade in the Arab world,” said Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko to his aids. “Other Arab countries should not be allowed to yield to the pressure of the Americans and join a separate deal.” He identified Jordan as “the weakest link,” and worried it was “playing a double game.” He concluded that “we must help friendly Arab countries to inflame the situation around this deal so that King Hussein would not dare to touch it,” and believed that Syria and the PLO were best suited to the purpose. He then proposed “a pilgrimage of Arabs to Moscow,” in which the Arab leaders would fly to the USSR in succession, with Assad going first; thereafter, the leaders would attend a Pan-Arab summit to condemn “Sadat’s apostasy.”[19] Against this backdrop, Egyptian and American efforts to convince the Soviets to support the Camp David peace process stalled.[18]

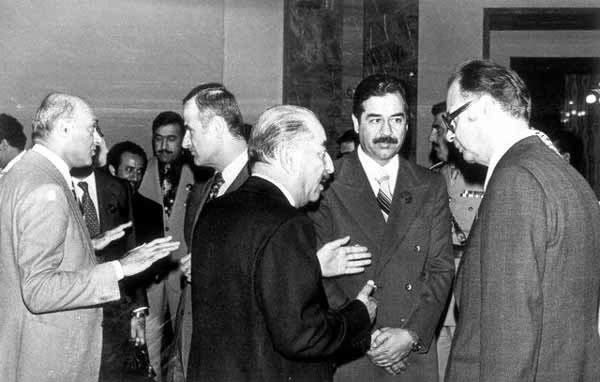

Assad visited Moscow on October 5th and 6th, representing the Steadfastness and Confrontation Front. The Soviets encouraged the Syrian-Iraqi rapprochement that had begun earlier that month. In doing so, they endorsed Iraqi calls to host the Pan-Arab summit in Baghdad, to which Assad responded positively three days after leaving Moscow.[19] This was a critical development for any hope of a united Arab front—not least because Syrian agreement to attend the summit meant the Steadfastness Front would join—especially considering the history of intense Syrian-Iraqi feuding, which had consistently frustrated the Soviets.[20] While Assad’s visit did not produce anything new in terms of Soviet-Syrian relations, it indicated the seriousness of both countries’ desire for closer ties.[21] In the weeks after Assad’s visit, Syria and Iraq concluded an alliance, guaranteeing that all the rejectionists would be present at Baghdad.[22]

PLO leader Yasser Arafat’s visit to Moscow in late October gave the clearest indication that an intensified anti-Camp David policy had taken root in the USSR. During their meeting with Arafat, the Soviets affirmed that “By taking this path, Egyptian President Sadat has thrown a noose on his neck and keeps tightening it at every step.” They also extolled the recent conference decisions of the Steadfastness Front, and emphasized the need to bring other countries into the fold, while warning of Saudi and Jordanian schemes to prevent Egyptian isolation at Baghdad. Arafat agreed and expressed his concern over the possibility of “imperialist forces” starting a conflict (or exacerbating an extant one) in Lebanon, southern Arabia, or on the Egyptian-Libyan border.[23] Most importantly, however, the USSR formally recognized the PLO as the “sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people.” This was a major shift in Soviet policy, as the USSR had previously refrained from such an acknowledgement, presumably to maintain some leverage over Arafat and his colleagues. Now, however, that recognition came without any significant concessions by the Palestinians, signaling the growing closeness between the USSR and the PLO, and indicating the Soviets’ clear commitment to align with the enemies of a separate peace.[24]

Playing for the Moderates

While the rejectionists consolidated their position, President Carter tried to engage the moderates. Carter warned his Arab interlocutors that a “lack of support from other responsible and moderate leaders of the Arab nations would certainly lead to the strengthening of irresponsible and radical elements and a further opportunity for intrusion of Soviet and other Communist influences throughout the Middle East.”[25] The State Department likewise focused on courting the moderate Arabs, although Secretary of State Cyrus Vance also met with President Assad on his way back from encouraging Jordanian and Saudi officials to support the Accords.[26]

Reactions were mixed. The Saudis responded relatively positively to American overtures. However, King Hussein of Jordan reacted negatively, requesting that the Carter administration formally answer fourteen questions about the Accords. Assad, whose meeting with Vance was delayed by the Steadfastness and Confrontation Front conference in Damascus, likewise demanded answers, peppering the Secretary of State with questions for four and a half hours before finally explaining that Syria could not accept the Accords as the basis for a comprehensive peace.[27]

With Saudi and especially Jordanian attitudes in flux, Jordan came to be seen by the Americans, Soviets, rejectionists, and moderates as the wildcard in the runup to the Baghdad Summit. King Hussein of Jordan was due to visit Moscow in mid-October, which the Kremlin saw as a critically important visit—one in which even General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, who had little appetite for Middle Eastern affairs, took a personal interest—but after meeting with Secretary of State Vance, the king decided at the last minute to send his brother Crown Prince Hassan to Moscow in his stead, which “upset” Brezhnev and “alarmed” Gromyko and KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov, as they worried it could signal a Jordanian shift in favor of the Accords. In response, the Soviets lowered the level of the meeting, giving negotiating duties to Premier Alexey Kosygin instead of Brezhnev.[28]

Upon receiving the official U. S. response to his fourteen questions on October 17—the night before the Soviet-Jordanian meeting—King Hussein informed American officials that he would make his decision closer to the Baghdad Summit. The king also expressed some openness to encouraging the West Bank Palestinians to participate in the peace talks, but lamented growing PLO influence in Palestinian politics, for which he blamed Saudi financial support to the group.[29] Meanwhile, Soviet discussions with Hussein’s brother, Prince Hassan, went fairly well, and while the Jordanian crown prince condemned the Accords less stridently than Assad had, he claimed that Jordan wanted a comprehensive peace, not a bilateral one. Kosygin therefore announced Soviet support for Jordanian opposition to the Accords.[30]

While the Soviets shored up their support for the rejectionist camp, which now seemingly included Jordan, Saudi Arabia’s stance was still somewhat unclear. The Saudis were under tremendous pressure from the rejectionists, as a steady stream of radical Arab leaders visited the Kingdom in hopes of consolidating a fully rejectionist front against the Accords and Egypt at Baghdad.[31] But to the Americans’ delight, the Saudis pledged themselves to encouraging moderate solidarity, assuring Sadat of support and warning the Iraqis against taking a radical position. They also developed a clever scheme to counter rejectionist pressure.[32] In mid-October, a South Yemen-led coup against ‘Abd Allah Salih, President of the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR, or North Yemen), had nearly succeeded with support from Libya and Iraq. If the radicals moved against Egypt at Baghdad, Saudi Crown Prince Fahd suggested, the YAR would formally complain about Iraqi-Libyan involvement in the failed coup. This Saudi “‘time bomb’ understanding with the YAR” was, in US Ambassador John West’s opinion, “a near genius political stroke,” as it could block official anti-Egyptian measures. The Saudis also planned to pressure the PLO into joining the peace process.[33] American officials hoped that if the Saudis played their Yemen card, it could prevent the Arab League from censuring Sadat.

Saudi plans aside, things looked bleak for supporters of the Camp David Accords. Not only had the Accords drawn opposition from the Front and Iraq, but they had also alienated Jordan and produced a Syrian-Iraqi rapprochement. Worse still, just three days before the Baghdad Summit, Brzezinski informed President Carter of CIA concerns that the moderates lacked a coherent strategy for protecting Egypt at the meeting.[34] All of this presented a serious obstacle to the peace process: if the moderates fell into the radical camp, they could not only make a comprehensive peace less feasible, but could possibly disrupt the separate Egyptian-Israeli peace.

Nevertheless, the Soviets were worried, too. They were unsure whether their efforts would be enough to overcome the “motley” interests of the Arab states and convince them to stand against the Camp David Accords. Indeed, shortly before the summit, it appeared that the Jordanians and Saudis might not condemn Sadat.[35]

Ultimately, however, the moderates had little to gain and much to lose by defending the Accords at Baghdad. Officials from both Jordan and Saudi Arabia knew the dangers of opposing the rejectionists, especially given the strength of the nascent Syrian-Iraqi alliance, the threat of ostracization from the rest of the Arab world, and concerns about regime stability, which could be threatened if they did not bolster their pan-Arab credentials. Furthermore, the recent expansion of Israeli settlements in the Occupied Territories and the Accords’ inadequacy on the Palestinian question—it did not contain an explicit provision for Palestinian statehood, and did not recognize the PLO as the sole legitimate representative of Palestinian interests—combined to make them resent the agreement.[36] Additionally, the radicals drew an already-dissatisfied Jordan closer with financial inducements, including $1.25 billion per year for ten years.[37] This combination of sticks and carrots ultimately compelled the Saudis and Jordanians to oppose the Camp David Accords at Baghdad.[38]

Conclusion

The moderates tried to temper the outcome of the Baghdad Summit, but met with mixed success. The Steadfastness Front and Iraq pushed for disciplinary action against Egypt, but Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and the Gulf States opposed them.[39] In a compromise, the two sides drew up—but did not immediately publish—potential punitive measures in case of an official Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty. A joint Jordanian-PLO commission was established, further healing the divide between them. The Saudis never put their Yemeni “time bomb” plan into action. Justifying their condemnation of the Camp David Accords to the Americans, they argued “the conference action would have been much more drastic without their moderating influence.”[40]

True as this might have been, the Camp David Accords and the moderates’ drift toward the rejectionists, Joseph Twinam writes, “offered the Soviet Union a new chance to get back in the game as a responsible great power,” leading to increased superpower competition in the region.[41] Just as seriously, the solidification of Arab opinion against the Camp David Accords threatened to block the path to peace in the Middle East, as it seemed to both foreclose the option of a comprehensive Arab-Israeli deal and endanger the Egyptian-Israeli negotiations themselves. This case of relatively weak states flexing their political muscle would ultimately force President Carter to further involve himself in a peace process that had already taken up so much of his time and domestic political capital. It also augured a new era of instability in the Middle East, just as the Iranian Revolution began to simmer and Soviet officials were poised to capitalize on America’s Middle East woes.

Benjamin V. Allison is a Ph.D student in History at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is also a Graduate Fellow at the Clements Center for National Security. His dissertation examines relations between the United States, the Soviet Union, and Arab “rejectionists” from 1977 to 1984. He also studies terrorism and has been published in Perspectives on Terrorism and by the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism.

[1] UK Embassy Damascus to FCO, “Arab/Israel,” March 15, 1979, FCO 93/2205, AMAD

[2] This article uses “rejectionist/s” and “radical/s” interchangeably. While there is debate over who the “true” rejectionists were and are—Israel or the Palestinians and Arabs—in the context of the Egyptian-Israeli peace process, the “rejectionists” were simply those that opposed that process. Seth Anziska, “Autonomy as State Prevention: The Palestinian Question after Camp David, 1979–1982,” Humanity 8, no. 2 (Summer 2017): 287-310; Noam Chomsky, The Fateful Triangle: The United States, Israel and the Palestinians, updated ed. (London, 1999); Colter Louwerse, “‘Tyranny of the Veto’: PLO Diplomacy and the January 1976 United Nations Security Council Resolution,” Diplomacy & Statecraft 33, no. 2 (2022): 303-329; Adel Safty, From Camp David to the Gulf: Negotiations, Language & Propaganda, and War (Montreal, 1992).

[3] Adeed I. Dawisha, The Arab Radicals (New York, 1986); William B. Quandt, Saudi Arabia in the 1980s: Foreign Policy, Security, and Oil (Washington, DC, 1981), 18-22.

[4] George W. Breslauer, ed., Soviet Strategy in the Middle East (London, [1990] 2016); Roland Dannreuther, The Soviet Union and the PLO (New York, 1998); Robert O. Freedman, Soviet Policy toward the Middle East since 1970, 3rd ed. (New York, 1982); Galia Golan, Soviet policies in the Middle East from World War Two to Gorbachev (Cambridge, 1990); Efraim Karsh, Soviet Policy towards Syria since 1970 (New York, 1991); Hafeez Malik, ed., Domestic Determinants of Soviet Foreign Policy towards South Asia and the Middle East (New York, 1990); Oles M. Smolansky with Bettie M. Smolansky, The USSR and Iraq: The Soviet Quest for Influence (Durham, 1991); Alexey Vasiliev, Russia’s Middle East Policy: From Lenin to Putin (London, 2018).

[5] See, for example, Martin Indyk, Master of the Game: Henry Kissinger and the Art of Middle East Diplomacy (New York, 2021).

[6] Aleksandr Belonogov, Na diplomaticheskoĭ sluzhbe v MID i za rubezhom [In the diplomatic service of MID and abroad] (Moscow, 2016), 327; Karen Brutents, Tridt͡satʹ let na staroĭ ploshchadi [Thirty years on the old square] (Moscow, 1998), 383.

[7] Memcon, “Meeting with President Giscard,” Monday, October 2, 1978, 1700-1805, and Memcon, “Meeting with Prime Minister Callaghan,” Wednesday, October 4, 1978, 10:05-11:20 a.m., Plains Files, Box 29, Folder 2, Jimmy Carter Library.

[8] Sadat, quoted in Quandt, Camp David, 273; UK Embassy Cairo to FCO, “President Sadat’s Speech,” October 3, 1978, FCO 93/1435, United Nations National Archives, Adam Matthew Archives Direct, archivesdirect.amdigitalco.uk (hereafter AMAD).

[9] September 22, 1978, Jimmy Carter, White House Diary (New York, 2010); Boutros Boutros-Ghali, Egypt’s Road to Jerusalem: A Diplomat’s Story of the Struggle for Peace in the Middle East (New York, 1997), 155.

[10] Secretary of State to Multiple Posts, “U.S. Support for Camp David,” September 26, 1978 (State 244085), US National Archives, Access to Archival Databases, aad.archives.gov (hereafter AAD). The embassies’ responses arrived on September 26–27. See Algiers 2739, Baghdad 1987, Damascus 5739, Tripoli 1354, Jidda 6908, Amman 7575, Sana 4822, Tunis 6867, and Cairo 21705, AAD. Situation Room to Brzezinski, “Additional Information Items,” September 30, 1978, NSA 1, Box 7, Folder 9, JCL.

[11] For private Soviet reactions, see Foreign Relations of the United States 1977–1980 (hereafter FRUS 1977–80) VI, docs. 145-146 and 150.

[12] “Final Communiqué of the Third Summit Conference of the Arab Front for Steadfastness and Confrontation States, Issued in Damascus, September 23, 1978 [Excerpts],” Journal of Palestine Studies 8, no. 2 (Winter 1979): 184-187. See also Department of State to US Mission to the Sinai, “Intsum 653—September 19, 1978,” FRUS 1977–80 IX, doc. 63; and US Embassy Damascus to Secretary of State, “Steadfastness Front Summit,” September 27, 1978 (Damascus 05738), AAD.

[13] Bassam Abu Sharif, Arafat and the Dream of Palestine: An Insider’s Account (New York, 2009), 57.

[14] Damascus 5738. See also Dishon and Ben-Zvi, “Inter-Arab Relations,” Middle East Contemporary Survey (hereafter MECS) II, 220.

[15] Sharif, Arafat and the Dream of Palestine, 58-59.

[16] Damascus 5738. See also Sonoko Sunayama, Syria and Saudi Arabia: Collaboration and Conflicts in the Oil Era (London, 2007), 50-51; and Karsh, Soviet Policy towards Syria, 118.

[17] Grinevsky, Taĭny sovetskoĭ diplomatii, 132-133, 143.

[18] “Zapisʹ besedy direktora Instituta Afriki AN SSSR An. A. Gromyko s vremennym poverennym v delakh ARE v SSSR g-nom ShELBAI,” October 5, 1978, R406, Box 23 (1978–July 1979), READD-RADD Database [hereafter READD], National Security Archive.

[19] “Meeting of the Political Consultative Committee of the Warsaw Treaty Member Countries,” November 22, 1978, and “Notes on Yasser Arafat’s Visit to Moscow in October 1978,” November 14, 1978, Cold War International History Project (hereafter CWIHP), digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org. On Syrian agreement to attend the Baghdad Summit, see US Embassy Damascus to Secretary of State, “Preparing for an Arab Summit: Iraq-Syria Rivalry,” October 12, 1978 (Damascus 6145), AAD.

[20] Brutents, Tridt͡satʹ let, 407; Brutents, in Lysebu I, 72; Grinevsky, Taĭny sovetskoĭ diplomatii, 134.

[21] “Iz sovmestnogo sovetsko-siriĭskogo kommi͡unik,” SSSR i Blizhnevostochnoe Uregulirovanie, 1967-1988: Dokumenty i materialy (Moscow,1989), doc. 151.

[22] Karsh, Soviet Policy towards Syria, 119; Embassy Damascus to Secretary of State, “Assad’s Moscow Visit,” October 5, 1978 (Damascus 05993), AAD; US Mission to NATO to Secretary of State, “Report on the Situation in the Mediterranean (Med Report) April–November 1978,” November 8, 1978 (US NATO 10219), AAD.

[23] “Notes on Yasser Arafat’s Visit to Moscow in October 1978,” November 14, 1978, CWIHP.

[24] Dannreuther, The Soviet Union and the PLO, 105-106.

[25] Carter to Hussein, Washington, September 19, 1978, and Carter to Assad, Washington, September 19, 1978, FRUS 1977–80 IX, docs. 61 and 62; “Camp David Frameworks for Peace (September 17, 1978),” in The Israel-Arab Reader, 609-615. For blow-by-blow accounts of the Camp David discussions, see especially Quandt, Camp David; Carter, Keeping Faith; and Wright, Thirteen Days in September.

[26] US Embassy Damascus to Secretary of State, “Delivery of President’s Letter to President Hafez al-Assad,” September 19, 1978 (Damascus 5475), US Embassy Beirut to Secretary of State, “Camp David: Guidance for Discussion,” September 21, 1978 (Beirut 5508), Secretary of State to US Embassy Khartoum, “Guidance for Post-Camp David Discussions,” September 23, 1978 (State 241998), and Secretary of State to US Mission to the UN, September 29, 1978 (State 248576), AAD.

[27] Secretary’s Aircraft to Secretary of State (Christopher), “Meeting with Assad September 24, 1978,” September 24, 1978 (SECTO 10071), AAD. See also US Embassy Damascus to Secretary of State, “SARG Request to Postpone Secretary Vance’s Visit to Damascus,” September 22, 1978 (Damascus 5584), NLC-16-45-4-36-2, CREST/RAC, JCL.

[28] Grinevsky, Taĭny sovetskoĭ diplomatii, 149-151.

[29] US Embassy Jidda to Department of State, “Talk With King Hussein,” October 18, 1978, 0950Z, and Embassy Jidda to Department of State, “Talk With King Hussein,” October 18, 1978, 1537Z, FRUS 1977–80 IX, docs. 91 and 92; See also Ashton, “Taking Friends for Granted,” 641.

[30] Grinevsky, Taĭny sovetskoĭ diplomatii, 151-152; “Soobshchenie o prieme chlenom Politbi͡uro T͡sK KPSS, Predsedatelem Soveta Ministrov SSSR A. N. Kosyginym naslednogo print͡sa Iordanii Khasana,” SSSR i Blizhnevostochnoe Uregulirovanie, doc. 152.

[31] Sunayama, Syria and Saudi Arabia, 52-53.

[32] Situation Room to Brzezinski, “Evening Notes,” October 8, 1978, NSA 1, Box 8, Folder 2, JCL.

[33] Memcon, Fahd and West, Jidda, undated [c. October 24, 1978], and Editorial Note, FRUS 1977–80 IX, docs. 106 and 124. See also Halliday, Revolution and Foreign Policy, 124.

[34] Brzezinski to Carter, “Information Items,” October 30, 1978, NSA 1, Box 8, Folder 3, JCL; NIDC 78/256, CIA FOIA. See also US Interests Section Baghdad to Secretary of State, “Iraqi-Syrian Rapprochement,” October 27, 1978 (Baghdad 2230), AAD.

[35] Grinevsky, Taĭny sovetskoĭ diplomatii, 156-157.

[36] Sharif, Arafat and the Dream of Palestine, 58-59; Michael N. Barnett, Dialogues in Arab Politics: Negotiations in Regional Order (New York, 1998), 194-195; William B. Quandt, Saudi Arabia in the 1980s: Foreign Policy, Security, and Oil (Washington, DC, 1981), 115; Joseph Kostiner, “Saudi Arabia and the Arab–Israeli Peace Process: The Fluctuation of Regional Coordination,” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 36, no. 3 (December 2009): 417-429.

[37] Patrick Seale with Maureen McConville, Assad of Syria: The Struggle for the Middle East (Berkeley, 1988), 313.

[38] Nigel Ashton, “Taking Friends for Granted: The Carter Administration, Jordan, and the Camp David Accords, 1977–1980,” Diplomatic History 41, no. 3 (2017): 620-645; Mahida Rashid al Madfai, Jordan, the United States and the Middle East Peace Process, 1974–1991 (Cambridge, 1993), 48-54; Secretary of State to US Embassy Amman, “Meeting with Sharaf in Algiers,” January 1, 1979 (State 14), AAD.

[39] Barnett, Dialogues in Arab Politics, 195.

[40] Jimmy Carter, Keeping Faith: Memoirs of a President (New York, 1982), 410.

[41] Joseph Wright Twinam, “Soviet Policy for the Gulf Arab States,” in Domestic Determinants of Soviet Foreign Policy, 249. See also Dishon, “Inter-Arab Relations,” 216.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.