Institute for Historical Studies – Wednesday, October 20, 2021

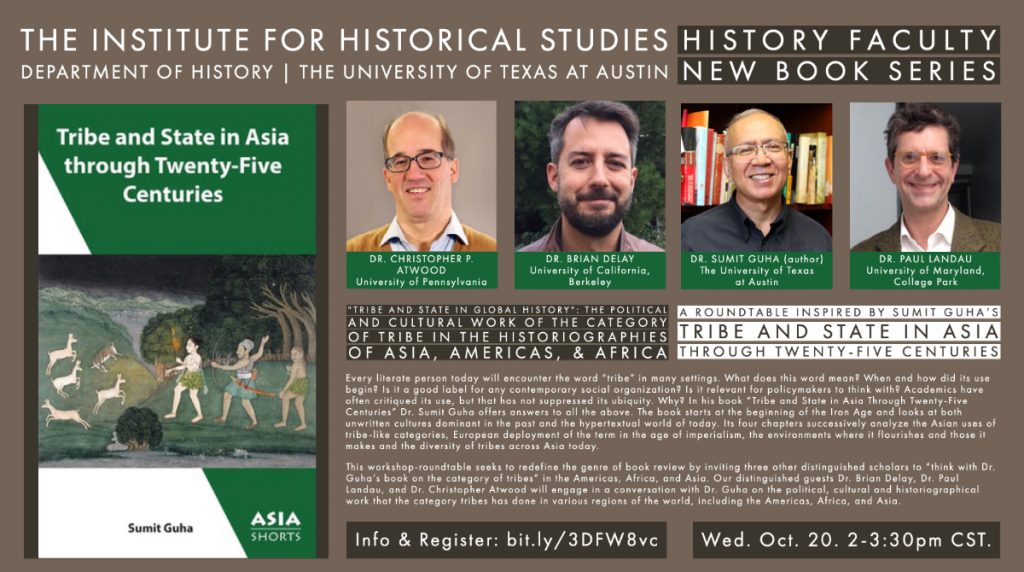

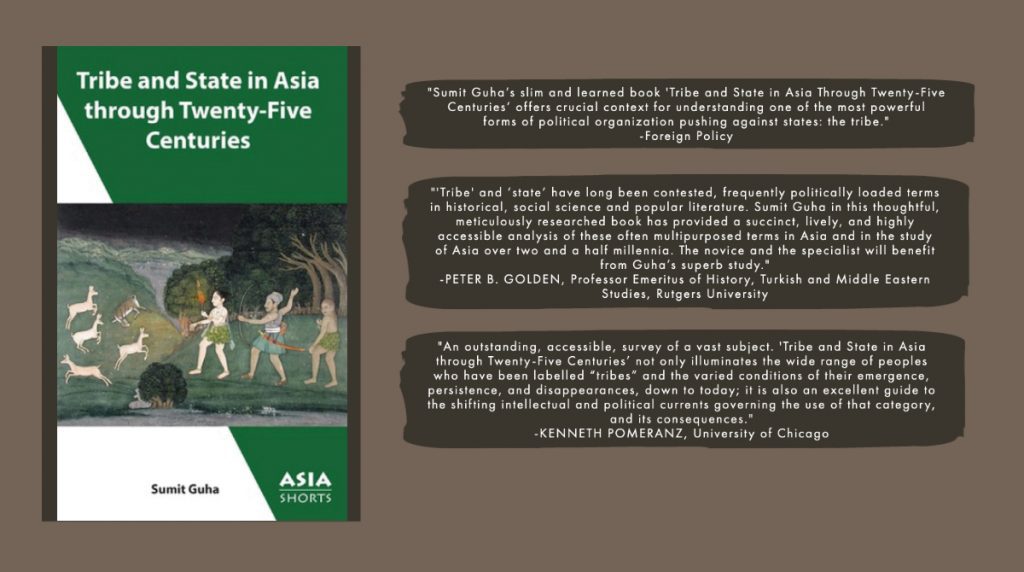

A Roundtable Inspired by Sumit Guha’s

Tribe and State in Asia Through Twenty-Five Centuries

(Columbia University Press, 2021)

Notes from the Director

Every literate person today will encounter the word “tribe” in many settings. What does this word mean? When and how did its use begin? Is it a good label for any contemporary social organization? Is it relevant for policymakers to think with? Academics have often critiqued its use, but that has not suppressed its ubiquity. Why? In his book, Tribe and State in Asia Through Twenty-Five Centuries, Professor Guha offers answers to all the above. The book starts at the beginning of the Iron Age and looks at both unwritten cultures dominant in the past and the hypertextual world of today. Its four chapters successively analyze the Asian uses of tribe-like categories, European deployment of the term in the age of imperialism, the environments where it flourishes and those it makes and the diversity of tribes across Asia today.

This workshop seeks to redefine the genre of book review by inviting three other distinguished scholars to “think with Guha’s book on the category of tribes” in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Our distinguished guests Brian Delay, Paul Landau, and Christopher Atwood will engage in a conversation with Sumit Guha on the political, cultural and historiographical work that the category tribes has done in various regions of the world, including the Americas, Africa, and Asia.

Author and discussants

Dr. Sumit Guha holds the Frances Higginbotham Nalle Centennial Professorship in History at the University of Texas at Austin. Educated at St Stephen’s College, Delhi, Jawaharlal Nehru University, and the University of Cambridge, he has taught at St. Stephen’s College, the Delhi School of Economics, Brown University and Rutgers University. Among his numerous books and co-edited volumes he is the author of History and Collective Memory in South Asia, 1200–2000 (University of Washington Press, 2019).

Featured discussants:

Dr. Christopher P. Atwood

Department Chair and Professor, Mongolian and Chinese Frontier & Ethnic History, University of Pennsylvania

“Responding to Sumit Guha’s Tribe and State in Asia through Twenty-Five Centuries is a bit awkward. Sumit makes extensive use of my works, but in the end does not quite agree with my conclusions. Like other ‘anti-tribals’ in my field of Mongolian studies (David Sneath, Lh. Munkh-Erdene), I see no useful role left for ‘tribe’ or ‘tribal’ in history or social science, while Sumit clearly does. So in the same spirit, let me point out ways in which Sumit is definitely right, and we ‘anti-tribals’ wrong, before I go on to profess myself not quite convinced by his arguments. The most important question Sumit gets right is that the term ‘tribe’ and ‘tribal’ seems here to stay. Although ‘barbarian’ or at least ‘feudalism,’ it hasn’t happened even in our own field. And it hasn’t happened because of certain ambiguities in our argument. The evidence for classic clans, avoidance, and anti-state dissidence is rather stronger among the Turks than it is among the Mongols. Our argument could have been, that Inner Asian tribes exist, just more among the Turks than the Mongols. But for reasons good and bad, we have mostly made arguments that the term ‘tribe’ just is not necessary. Not surprisingly, Turcologists have most dismissed our work, insisting that all nomads are tribal, Turk and Mongol alike. Perhaps we should have accepted half a loaf and just argued, yes Turks have tribes, but Mongols don’t. Instead we have gotten no loaf at all: tribes are still used for both. But in the end, the sticking point for me is that I can’t get away from the relational nature of the designation ‘tribe.’ In Sumit’s survey the most powerful and convincing parts come precisely where he treats tribe as a tool in states’ handling of those in relation to, but not fully incorporated, in themselves. That being the case, then I still have deep reservations over any use of tribe’ outside of such a relational context. As ‘minorities’ only exist in relation to ‘majorities,’ so ‘tribals’ exist only in relation to ‘states.'”

Dr. Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra

Director, Institute for Historical Studies, and Alice Drysdale Sheffield Professor of History, The University of Texas at Austin

Behetria and the Iberian political ecology of tribe and state in the 16th-century American borderlands

The Iberian conquest of America is ungraspable without the ongoing production of knowledge on borderland insurgencies from Parral Chichimec to New Mexico Pueblos to Chilean Mapuches, with a whole gamut in between. I would like to focus on sociological models of borderland insurgencies in the 16th century Spanish empire that culminated with a treatise on political ecology and sociology of state building, namely, Jose de Acosta’s Procuranda Indorum Salute (1588) an immense learned treatise on “conversion” in three types of places and circumstances: decentralized borderlands, “barbarians” (from Mexico to China), and civilized Counter Reformation European societies. Central to Acosta is the notion of political ecology: one changes the place one changes the people. There is a an evolutionary, teleological dimension to this but also an element that might be overlooked in Sumit’s wonderful study of term and theories used by of lay northern European imperial bureaucracies: it is the religious dimension of many of these “European” ideas. There are uncanny resemblances between all state bureaucracies in relationship with the borderland insurgencies, regardless of whether they are western or non-western, lay or religious.

Dr. Brian DeLay

Associate Professor, and Preston Hotchkis Chair in the History of the United States, University of California, Berkeley

“I see three basic contexts in which the term is deployed in North America vis-a-vis Native People, all of which resonate in interesting ways with Sumit’s material from India. The first is as a (usually contemptuous) category in political comparison. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, European and Euro-American commentators in North America generally used nation and tribe interchangeably when referring to Indigenous polities. When commentators wanted to denigrate Indigenous polities relative to western states, however, (as in the commerce clause of the U.S. Constitution), “tribe” was invoked. Justice Marshall famously characterized “tribes” as “domestic dependent nations.” The purposely diminished sense of the term becomes more common as the power of the settler state increases across the 19th century. The second use for ’tribe’ is as a legal term. As Sumit describes for India, tribe is obviously still a consequential legal category in the U.S. today. There are 574 federally-recognized “tribes” and 63 state-recognized “tribes,” and those legal designations carry with them very significant political and economic consequences. Third and finally, tribe is a social-science term for a particular kind of socio-political organization. At its most lazy and expansive, it has been deployed to encompass all or nearly all Indigenous societies in North American history. That static and essentializing use fo the term has been rightly tossed aside in most academic writing. But, like Sumit, I think that the term still has diagnostic value. Specifically, we need a term to describe dynamic manifestations of Indigenous political and economic activity that unfold above the level of the family or band but below the level of trans-national (or pan-tribal) confederacy. If we don’t use “tribe” for that purpose, we’ll need an alternative.”

Dr. Sumit Guha

Frances Higginbotham Nalle Centennial Professorship in History, The University of Texas at Austin

“I am grateful for the careful reading and interesting comparisons offered by my colleagues. I am especially delighted that my book has connected with world regions that my limitations did not allow me to cover. My purpose throughout the book has been to demystify categories without necessarily casting them aside. Obviously I am working with a model of states making and dissolving tribes along with tribes breaking and making states. Then one must recognize the tribal basis of faiths and the devotees growing into a tribe and I see this as a recurring process in history, not an evolutionary stage. I hope it is evident that I personally prefer the individualistic civic model of citizenship rather than any of those I have discussed in my book. But citizenship too makes the moral demands of solidarity and sacrifice, as the tribe and the empire do. It is in that context, that I have also offered an implicit social psychology of political forms, especially of the tribe. It obviously rejects the binary offered by flatter versions of economics and sociology. The former starts with the premise of atomized individuals making selfish choices; the latter with structures that deny individuals any choices”

Dr. Paul Landau

Professor of History, University of Maryland, College Park

“Sumit Guha offers a fascinating history of what may defensibly be termed tribes in Asia. In Africa south of the Sahara, however, in general, it is harder to conceive of such a history without replaying colonial fantasies. That is because “tribe” was an administrative shorthand (woven into certain kinds of public discourse) to serve for all magnitudes of association — so long as a local apparent human diversity obtained. Guha finds a commonality (or a cloud of uses): kin-ordered, mobile, small (1000 to say 10,000), segmentary, clan-based, but in Africa this this was a survival strategy dating from the era of the slave trade and pertaining to terrain (mountains etc. as per Jim Scott). The idea of ethnicity does not clarify things: Pairing Yoruba with Tiv, Ndebele with Tswana, etc. forgets that each “group” had an historical trajectory that registered at different levels of expression making nonsense of any single category. (I will briefly unpack these ethnic names in my five minutes to demonstrate this concretely and why we perhaps should not in my view write a history of tribes in Africa.) It was not as a side effect, but the purpose of ethnic shorthand/tribe as a late colonial administrative fiction to cover up a patriarchal unconcern about borders of group subjects. And yet ethnic identities and tribal identities (apparently universal but not so) developed in urban spaces especially out of this very history of opacity, which deserves committed attention.”

This discussion is part of the IHS History Faculty New Book Series.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.