JapanLab aims to reimagine Japanese Studies at the University of Texas at Austin and in so doing to establish a template that can be replicated at other institutions across the country. It will prepare undergraduates and graduate students for an altered employment landscape by integrating digital dexterities across different aspects of the Japanese Studies curriculum and by creating a specialized space, JapanLab, where students will develop a wide array of digital resources with a focus on fully functional educational video games built around topics in Japanese history, language and literature. It seeks to recruit but also to train two external postdoctoral fellows, who will emerge from the experience with new skills as they work closely with JapanLab faculty and students. Finally, building on a successful pilot program JapanLab will generate a steady stream of Japan-focused educational video games and other Digital Humanities content that can be used in classrooms across the world.

The COVID-19 pandemic has altered the educational and employment landscape with breathtaking speed. Changes that might have taken decades were compressed into just a few months. Today, educators in Japanese Studies and beyond face three distinct challenges. First, undergraduates graduating university in 2020 require a suite of digital skills, often labelled as digital dexterities, to compete in a modern labor market in which they will be called upon to move between different platforms while engaging in frequent upskilling. Second, changes in the academic job market require graduate students, as well as recent PhDs, to develop a range of skills so they can work in different fields both inside and outside of academia. Third, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced educators to reimagine their classrooms almost overnight, there has been an unprecedented demand for free digital teaching resources vetted by scholars. 2020 saw an educational revolution that shifted the parameters of the traditional lecture/seminar model. Even after we return to in-person teaching, there is a clear and expanding need to engage students with high-quality, interactive digital content.

These challenges are substantial. JapanLab seeks to address them in an innovative and forward-looking way. It aims, first, to bring technology more fully into our classrooms by making digital dexterities a core component of Japanese Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. Second, the project will open up new pathways for current doctoral students in Japanese Studies and recent PhD graduates from other institutions that will help them navigate a

transformed employment environment. Third, the project will create a collaborative learning space, JapanLab, where teams of students can build sophisticated digital projects including educational video games. This will be housed physically in the Department of History which has committed, in tandem with a major university investment, to providing a dedicated workspace equipped with all the necessary technology. Once in place, JapanLab will generate a steady pipeline of digital content in Japanese History, Literature and Language that can be used by teachers across the world.

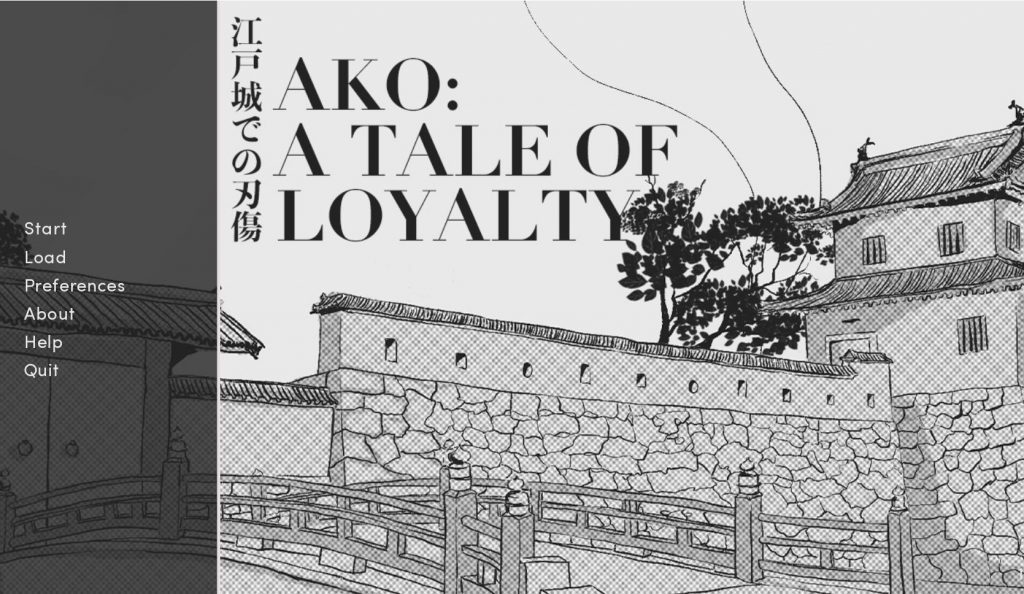

These ambitious goals are rooted in the strengths of the participating individuals and programs. They also build off a highly successful pilot program led by Adam Clulow that saw a team of four students create a historically accurate, Japan-focused video game across the course of a single semester. In Spring 2020, the Department of History asked four undergraduate History majors with no specialized games design background to develop a fully functional video game built around a specific historical topic and using only freely available platforms.

Promotional video for Ako: A Tale of Loyalty

The game had to draw from the latest scholarship and to incorporate a series of teaching points, allowing it to be deployed in high-school or college level classrooms. The result was impressive: a deep learning experience and a fully functional game, Akō: A Test of Loyalty, that is linked to contemporary scholarship. Akō: A Tale of Loyalty puts the player in Japan in 1701 in the role of a young samurai born into a low-ranking family that is struggling to survive. The game exposes players to the realities of samurai life, the economic structures of early modern Japan, the role of women and family, the commercialization of religion, and the nature of samurai ideologies in an age of peace. The program and the resultant game demonstrated clearly how digital resources could be harnessed to drive learning outcomes, but this requires a clear structure and additional funding to be scaled up.

Comments from Ashley Gelato, a member of the Ako games design team

DH Japan is comprised of three pathways that will feed students into JapanLab. The first pathway comprises specialized Digital skills courses. Second, DH Japan will teach DH focus courses. These are courses that are effectively born digital with a suite of scaffolded assignments that serve to advance critical skills. A third pathway, DH modified courses, will enable existing Japanese Studies courses to be retroactively engineered with Digital Humanities assignments and content. These three pathways will flow into JapanLab where teams of students will work on games and digital projects internships that will produce high-quality digital content that can be used at the University of Texas and beyond. JapanLab is divided into three units each under the charge of a different core faculty member.

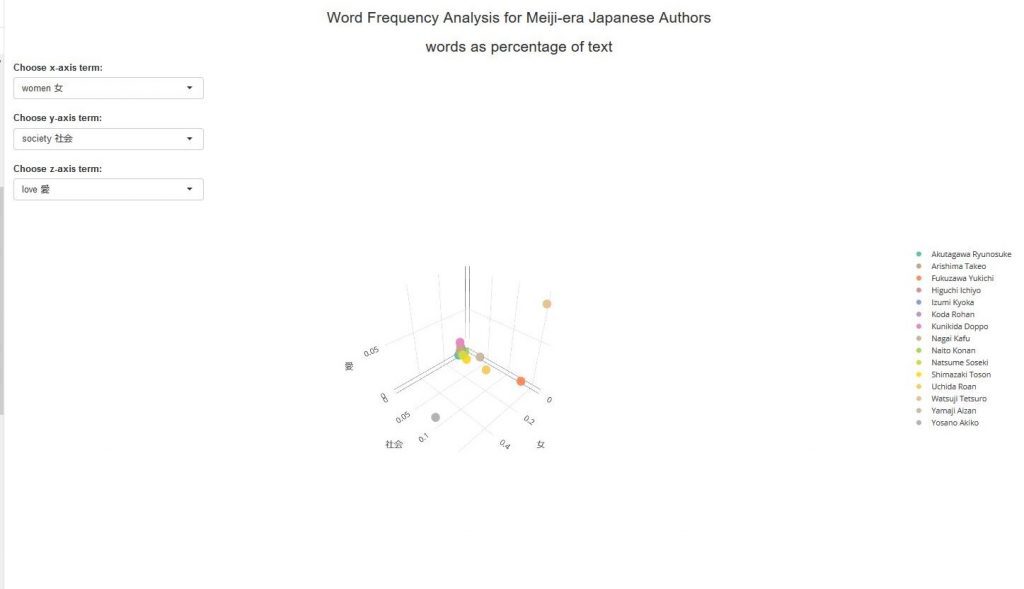

First, a Digital Projects unit led by Mark Ravina. This will generate an array of digital projects focused on digital dashboards. The shift to distance learning has highlighted the need for instructional tools that support active learning. Dashboards allow end users to explore a dataset through search boxes and pulldown menus and graphically display results. Dashboards are best known as a component of “business intelligence” (BI), which is a multibillion-dollar industry, but they are equally suited to a range of Japanese Studies topics, including the analysis of literary and historical texts, as well as social, economic, and demographic data. The Digital Projects unit will produce a wider array of dashboards that will advance student learning while providing tools and content for wider distributio

Second, a Historical Games Design Unit led by Adam Clulow. In the past few years, the barriers to game design have come down significantly. Free, publicly available platforms like Ren’Py incorporate a simplified coding language that allows the rapid development of standalone games. The Historical Games Design unit builds off a successful pilot program run in early 2020 that produced an immersive game focused on the Akō incident. As this showed, the process

of designing a game produces a level of familiarity with material that is not duplicated in typical college-level assignments. Crafting believable central characters, designing branching storylines, conceptualizing different choices for players and creating associated artwork all represent significant challenges that combine to drive student learning forward while giving them ownership over the final product. At the same time, designing a game requires students to master an array of digital dexterities. Games produced in this unit will explore key moments in Japanese history while developing content that can be used in a range of different classrooms.

Third, a Language, Literature and Technology Unit led by Kirsten Cather. Research has shown that games can be used to drive language acquisition, but few programs have sought to explore this nexus in a systematic way. Developing language games will allow students to grapple with language structures while also designing new educational tools that can be used in a range of classrooms. The Language, Literature and Technology Unit will, in addition, develop

games and technologies that will enable students to explore literary texts and literary language in greater depth. Many games are based on classic works of literature (see, for example, the viral success of Walden, A Game) and they provide a natural way to work through texts both as a narrative art and as a sociocultural artifact. Japanese literary works offer diverse opportunities for digital exploration from the tenth century Tale of Genji to IQ84, Murakami Haruki’s 21st century take on Orwell’s classic. Here too, texts in the original language can be incorporated to serve the purpose of both literary and language study.

Together these three units will generate a steady stream of digital content that will be made available on a JapanLab portal. We will also host a specialized Games expo event at the end of each academic year to showcase the projects produced by students. The result will be not only to advance learning outcomes at UT but also to provide digital content for use more generally.