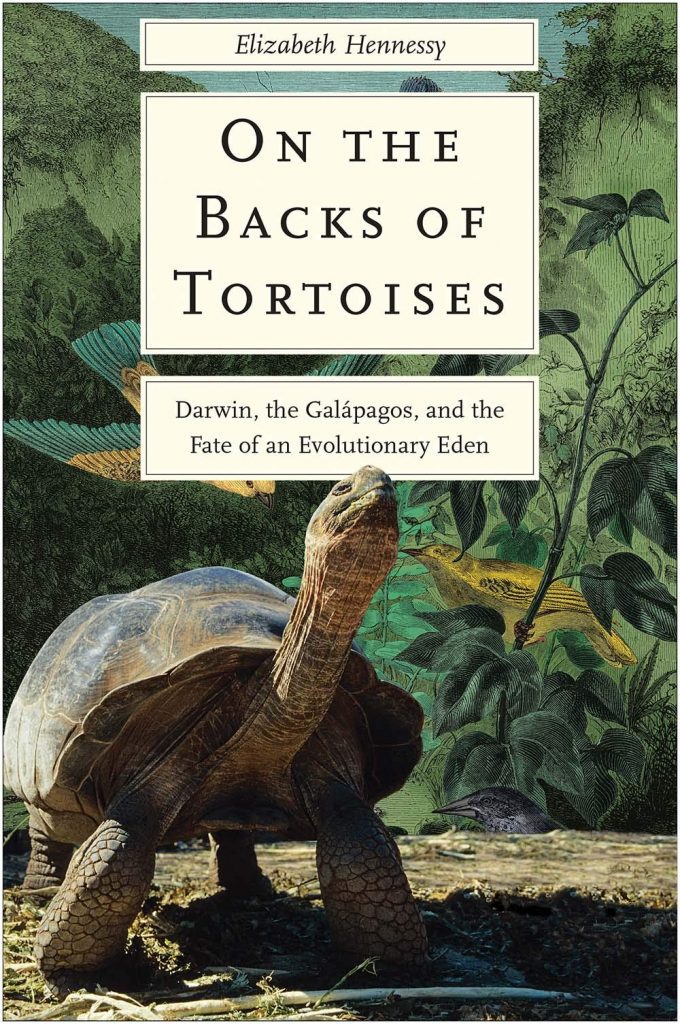

On the Backs of Tortoises: Darwin, the Galápagos, and the Fate of an Evolutionary Eden. By Elizabeth Hennessy. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019. xx + 310. 20 illustrations, notes, 4 maps, bibliography, and index. $30.00.

Located about 400 miles off the coast of Ecuador, the Galápagos Islands hold profound cultural importance as symbols of conservation, wild nature, and biodiversity. Charles Darwin visited the islands in 1835 and his encounters with the fauna of the Galápagos went on to shape his 1859 work On the Origin of Species. In contemporary times, statues of Charles Darwin await tourists in almost all of the small settlements on the islands. Scientists with UNESCO, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, and the Charles Darwin Research Station on the archipelago, architects of the current conservation project, present conservation as a continuation of Darwin’s legacy. However, in many ways, by seeking to reconstruct a pure “state of nature,” the conservation efforts that started to take shape in the 1930s have led to a contradictory project of stripping the islands of past traces of humanity through far-reaching and sometimes violent intervention.

In On the Backs of Tortoises, Elizabeth Hennessy frames the lumbering, armored reptilians of the Galápagos as “boundary objects”—material points of convergence between different spheres of action—that have been encoded with seemingly bottomless layers of meaning over time. First encountered by desperate sailors or pirates in the South Pacific as a live-saving source of food and water, turtles have been transformed by scientists, international mass media, and tourism into conservation icons and the recipients of legal protections. Simultaneously, local fishermen, often demonized by international media, despise the turtles as a metonym of the broader conversation project.

Drawing from extensive fieldwork conducted in the Galápagos working alongside scientists, as well as archival research using a mix of unpublished correspondence and published scientific articles and books, Hennessy weaves together a lively and engaging historical narrative that shines a light on the contradictions inherent in the current discourse of biological conservation. While conservation is often misrepresented as apolitical, Hennessy shows how the movement to establish the islands as nature preserves represented a continuation of imperial power dynamics. The Ecuadorian state had a vested political interest in developing the archipelago, which clashed directly with the interests of American and European scientists who wished to prevent species like the giant tortoises from going extinct. Although the local economy depends on tourism and the conservation industry, living in a nature preserve subjects galapagueños to increased policing and restriction. In fact, many of the leading scientists at the research station openly discuss the very presence of people in the Galápagos as a nuisance.

In this way, Hennessy’s work inserts itself into well-established historiographical conversations about colonial conservation initiatives in environmental history. Others works along similar lines include Richard Grove’s Green Imperialism or Ramachandra Guha’s The Unquiet Wood. At the same time, the book is also well-grounded in methodologies from the history of science. This shows through particularly well in Hennessy’s fieldwork with the scientists and fishermen of the Galápagos. Bringing these two fields into conversation, combined with interventions drawn from political ecology and animal history, she destabilizes hegemonic assumptions about the difference between “nature” and “culture,” which have informed the development of the conservationist discourse. Though she acknowledges that the consciousness of the tortoise lies beyond human comprehension and biologists know very little about their sensory or cognitive faculties, she nonetheless effectively shows their ability to transform local landscapes and vegetation patterns. More significantly, she demonstrates their semiotic function as a multifaceted “object” deeply embedded in political and cultural discourse. Rather than a tortoise-eye view of history, this remains a history centered on human interactions with and perceptions of tortoises.

A well-written and engaging book on a topic that many students will have at least some cultural knowledge (and likely many misconceptions) about, On the Backs of Tortoises would make excellent reading for any class on the history of science, environmental history, or the history of tourism. Due to the accessible style and the captivating narrative, the book will also appeal to many members of the general public, especially anyone who works in or has an interest in biology or conservation. The questions Hennessy raises about the fraught, entangled relationships among scientists, society, and the non-human world, as well as her treatment of the tortoises as historical actors, will surely help drive interesting and productive discussions. This book deserves praise for so effectively presenting the history of a place popularly constructed to lie outside the domain of human affairs to readers in an accessible, coherent way.

________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.