by Paula O’Donnell

In honor of the centennial of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, the 2022 Lozano Long Conference focuses on archives with Latin American perspectives in order to better visualize the ethical and political implications of archival practices globally. The conference was held in February 2022 and the videos of all the presentation will be available soon. Thinking archivally in a time of COVID-19 has also given us an unexpected opportunity to re-imagine the international academic conference. This Not Even Past publication joins those by other graduate students at the University of Texas at Austin. The series as a whole is designed to engage with the work of individual speakers as well as to present valuable resources that will supplement the conference’s recorded presentations. This new conference model, which will make online resources freely and permanently available, seeks to reach audiences beyond conference attendees in the hopes of decolonizing and democratizing access to the production of knowledge. The conference recordings and connected articles can be found here.

En el marco del homenaje al centenario de la Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, la Conferencia Lozano Long 2022 propició un espacio de reflexión sobre archivos latinoamericanos desde un pensamiento latinoamericano con el propósito de entender y conocer las contribuciones de la región a las prácticas archivísticas globales, así como las responsabilidades éticas y políticas que esto implica. Pensar en términos de archivística en tiempos de COVID-19 también nos brindó la imprevista oportunidad de re-imaginar la forma en la que se llevan a cabo conferencias académicas internacionales. Como parte de esta propuesta, esta publicación de Not Even Past se junta a las otras de la serie escritas por estudiantes de posgrado en la Universidad de Texas en Austin. En ellas los estudiantes resaltan el trabajo de las y los panelistas invitados a la conferencia con el objetivo de socializar el material y así descolonizar y democratizar el acceso a la producción de conocimiento. La conferencia tuvo lugar en febrero de 2022 pero todas las presentaciones, así como las grabaciones de los paneles están archivados en YouTube de forma permanente y pronto estarán disponibles las traducciones al inglés y español respectivamente. Las grabaciones de la conferencia y los artículos relacionados se pueden encontrar aquí.

Few organizations have names that so poignantly express their general mission. Memoria Abierta, whose name means “open memory” in Spanish, works to prevent Argentina from forgetting its difficult history. Specifically, Memoria Abierta educates Argentines about the deadly crimes committed by the 1976-1983 military government and, more importantly, the heroic resistance of human rights activists who fomented its demise. Part archive, part tech firm, part research center, part advocacy group, this organization has undertaken a broad range of initiatives across the past twenty years, all directed to this aim.

Memoria Abierta is principally an archival project, first organized by eight human rights associations in 2000. A non-governmental organization (NGO), Memoria Abierta operates independently from state agencies and political influence. Memoria Abierta’s chief investigator Dr. Cecilia Flores clarified that this status, unusual for archives in Argentina, protects the institution’s autonomy in a political context where governmental transition can imply “drastic turns” in official attitudes towards collective memory. “We believe that our archives should remain within civil society,” she explained. Her view is understandable considering Argentina’s turbulent political history and the legacies of the military dictatorship that motivated Memoria Abierta’s work in the first place.

The brutal military regime that gave impetus for Memoria Abierta ruled Argentina between 1976 and 1983. Although Argentines had already endured five military coups in the twentieth century, this new dictatorship was of a different kind. These new juntas detained, tortured, and killed an estimated 30,000 civilians for suspected “subversive” activity. State forces kidnapped and tortured these detainees before dropping them alive into the Atlantic Ocean. As their bodies were never found, the missing were hence known as los desaparecidos, or “the disappeared.”

Under these circumstances, family members of victims and their sympathizers mounted a courageous resistance against the dictatorship. Perhaps the most famous among them, Las Madres de la Plaza de Mayo, were middle-aged and elderly women who lost children and husbands to the military’s brutality. Beginning in 1977, these women met at the presidential palace every Thursday to hold vigil, wearing images of their missing kin on strings around their necks and plain white handkerchiefs on their heads.

Such censure of the junta’s atrocities, along with general dissatisfaction in Argentina over the failing economy, threatened the military state’s hold on power in the early 1980s. In a massive demonstration on March 30, 1982, activists demanded that the dictators step down and reinstate democratic elections. Three days later, the governing junta under General Leopoldo Galtieri invaded the Falklands/Malvinas islands in the South Pacific. They hoped the operation would rouse popular support. Initially, this worked: massive crowds celebrated the invasion in front of the presidential palace. However, when the Argentine garrison lost the islands to a dominant British taskforce in only two months, the humiliated and rebuked military regime abdicated power.

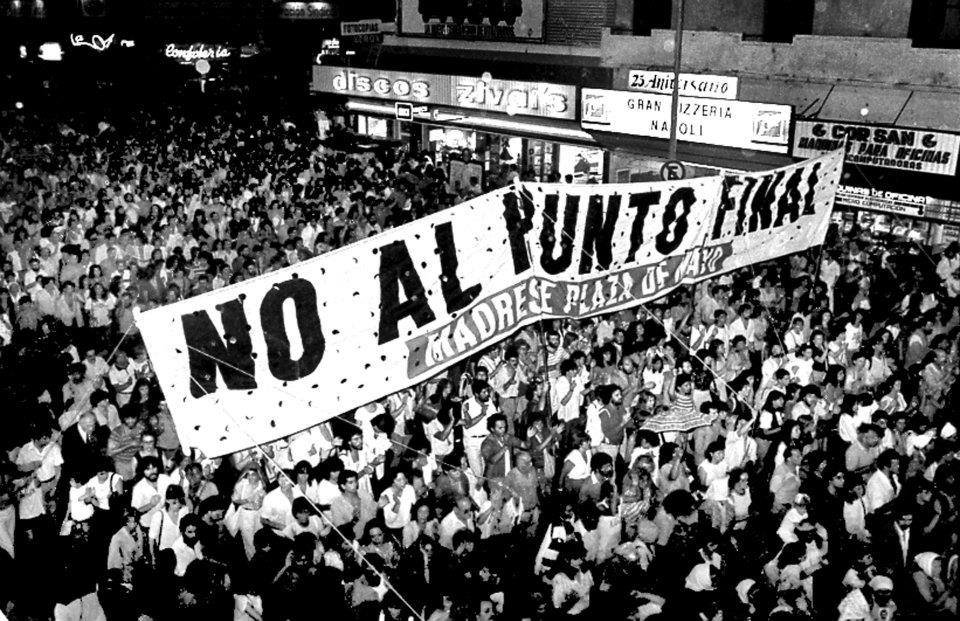

After the junta finally stepped down in 1983, there was much work for human rights activists to do. The family members of disappeared persons who integrated Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo, Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, Familiares de Desaparecidos y Detenidos por Razones Políticas, and other organizations still sought answers regarding the fates of their missing loved ones. The military continued to insist that they had no information about the disappeared, nor who was responsible for their disappearances. In response, the human rights organizations took to the streets, demanding that their former oppressors be held accountable in the court of law.

These “years of impunity,” in which the perpetrators walked freely while human rights organizers called for their arrest, would last for nearly two decades. The nine junta leaders who ruled between 1976 and 1983 were indeed brought to trial and some convicted in 1985—a historic achievement among Latin American post-dictatorial democracies. However, the still-powerful military establishment restrained the civilian administration of President Raul Alfonsín from prosecuting any officers besides the junta leaders. The Full Stop Law (Ley de Punto Final) and the Due Obedience Law (Ley de Obediencia Debida) officially shut down the transitional justice movement shortly after the junta’s convictions. To make things worse, President Carlos Menem eventually pardoned the few commanders who had gone to prison in 1989 and 1990. It was not until Argentina’s Supreme Course declared the Full Stop Law, Due Obedience Law, and amnesties as unconstitutional between 2005 and 2007 that the judicial process could take full course.

Memoria Abierta was established in 2000, just a few years before prosecutors reopened court cases against the perpetrators of the Dirty War. Eight human rights organizations, including Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo and Familiares de Desaparecidos y Detenidos por Razones Políticas, formed the NGO to systematize, catalogue, and index their individual collections, making them more accessible and legible to the public. These documents offer researchers “reflections on resistance,” according to Dr. Flores, emphasizing the experiences of those who bravely opposed the military regime.[1]

Memoria Abierta was thus born as an archival project, but it soon adopted investigative and pedagogical missions as well. For example, Memoria Abierta immediately began assembling what became a groundbreaking oral history collection.Eager to document the life experiences of elderly human rights leaders, Memoria Abierta researchers decided to interview them. They started with the founders and members of the eight human rights organizations constituting Memoria Abierta but then expanded to include activists and victims of state violence outside the coalition. Today the archive consists of more than 962 interviews with individuals that include survivors of detainment, artists exiled during the military regime, and political leaders who bravely challenged the dictatorship.

Memoria Abierta has also experimented with technological development, producing educational digital tools and platforms that have been used in classrooms, museums, and even as evidence during judicial proceedings. The first of these projects comprised a series of interactive CDs for public schools, produced in collaboration with the Department of Education for the city of Buenos Aires. Using these CDs, children learned about the dictatorship through TV news clips, oral history recordings, and other audiovisual sources

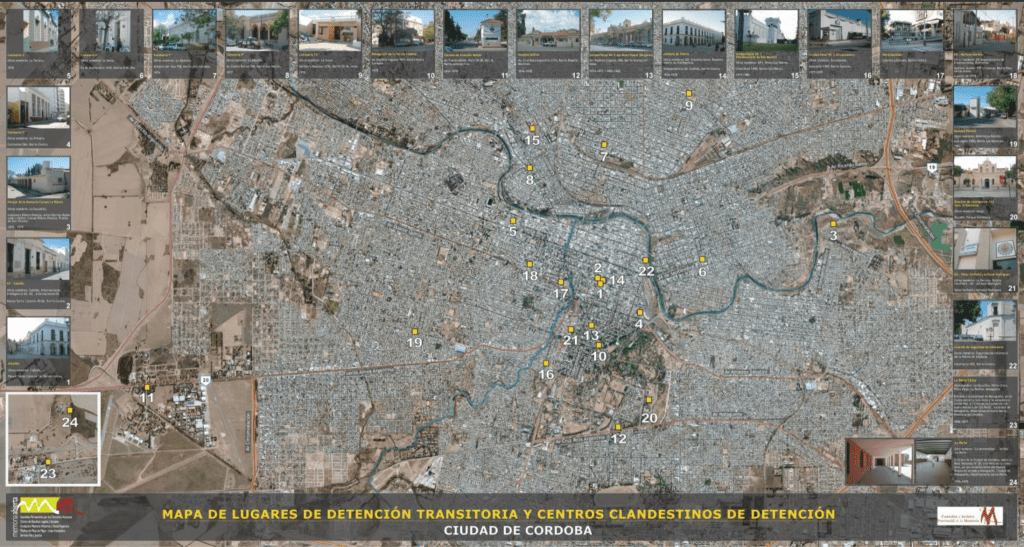

As part of their commitment to promoting sites of memory in Argentina, Memoria Abierta joined state-led initiatives to transform former detention centers into museums and memorials. These “sites of memory”, to use a term coined in the 1970s by French historian Pierre Nora, are spaces preserved or reconstructed to stimulate a community’s memory of the past. Visitors to these sites in Argentina walk through the spaces where state forces detained and tortured victims, learning about this horrifying history from trained guides. In situations where the outgoing military destroyed the sites, a reconstruction effort took place, often informed by documents, digital tools, and oral histories provided by Memoria Abierta.

The NGO also developed pedagogical resources for many of these sites of memory. For example, Dr. Flores showed me a digital mapping project that geographically reconstructs the routes taken by detained victims between different clandestine centers. Once completed, the cartographical tool will be projected on monitors at the former clandestine torture center known as “El Olimpo.” This project is illustrative of Memoria Abierta’s emphasis on what it calls “memory-based topography,” a kind of site-based memory-work in which maps, volumetric representations, and animations are used to visually reconstruct the territorial dimensions of the military regime’s repression.

Over the past twenty years, Memoria Abierta has become a household name in Argentina. As an Argentine-born female historian of the regime, I have long been familiar with their high-profile projects, including the digitization of newspapers transcribing the 1985 Trial of the Juntas. The organization’s enormous influence can be attributed to the NGO’s principled dedication to broad public access. Memoria Abierta insists on making all its resources available for public use, online whenever possible. This prioritization of public pedagogy is a crucial aspect of the organization’s framework for transitional justice. And this approach is critical. If all Argentines have access to the documents, the audiovisual material, and the digital tools produced and curated by Memoria Abierta, the lessons in these resources become “the instruments for strengthening democracy,” as Dr. Flores eloquently puts it.[2] In other words, by learning about the decades of struggles against state violence and impunity in Argentina, Argentines may be inspired to continue fighting for a just future in the present.

If you would like to learn more about Memoria Abierta, Dr. Flores represented the organization at the 2022 Lozano Long “Archiving Objects of Knowledge with Latin American Perspectives” Conference. Memoria Abierta participated in a panel entitled “’(Re)conociendo’: Community rights through archives and memory,” which is now available online.

[1] Maria Celina Flores, “Conocer el movimiento de derechos humanos a través de sus archivos. Experiencias sobre tratamiento de fondos documentales, accesibilidad y usos en Memoria Abierta,“ in Archivos Para La Paz Seminario Internacional: Diálogos de la Memoria, Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica, Colombia, 2015, pg 11.

[2] Ibid.

Paula O’Donnell is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History of UT Austin. Born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, her research interests include “Third World” discourses, gendered notions of citizenship, and military culture in Cold War Latin America. O’Donnell’s dissertation, “Defending La Argentina: Sovereignty and Honorable Citizenship in the Malvinas/Falklands War,” examines the Argentine military junta’s justifications for the 1982 conflict with Great Britain over the South Atlantic archipelago. The project, informed by social science, feminist, and postcolonial theory, offers new insights into right-wing authoritarian nation-building in Cold War Latin America. Archival research for this project, funded by the AHA’s Conference on Latin American History and the University of Texas Graduate School, is underway this year in Buenos Aires.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

![“En las urgencias de la realidad [Within the urgencies of reality]:” Perspectives about the Vicaría de la Solidaridad](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Lozano-Long-Conference-1-1-150x150.png)