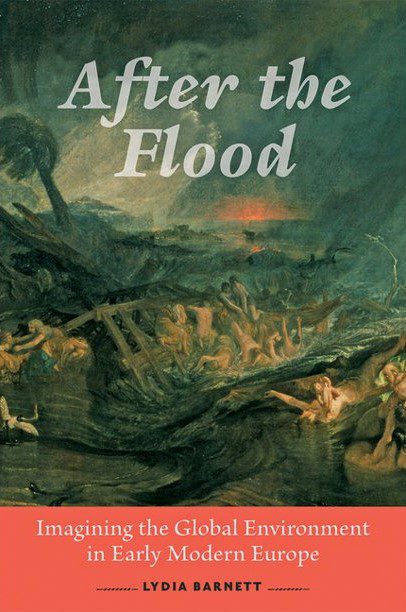

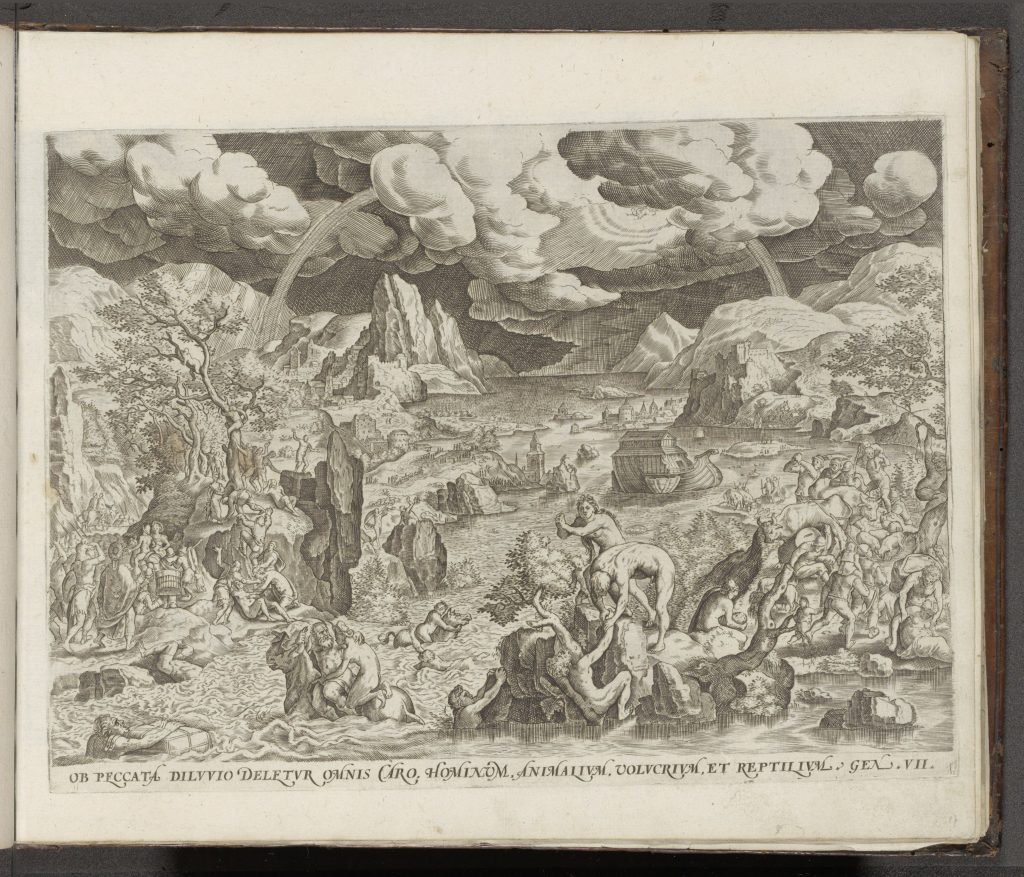

Lydia Barnett’s first book, After the Flood, examines how early modern Europeans sought to understand the relationship between human activity, morality, and the environment through narratives of Noah’s flood. Barnett frames her post-Medieval history through the modern concept of an Anthropocene, or an era in which humans are a dominant influence on the environment. Although this term was coined to describe how man-made greenhouse gases have altered the planet since the Industrial Revolution, Barnett’s anachronous use of the term reveals a previously unexplored throughline in environmental history.

As a historian of science and religion, Barnett analyzes European texts from the 1570s to 1720s to expand upon two decades of scholarship on the advent of environmental consciousness in Europe and the relationship between religious and scientific knowledge. She contributes to academic conversations on the advent of the Anthropocene, arguing that a theological concept of man’s impact on nature and climate preceded the geological concept proposed in the twentieth century. Barnett also engages with foundational texts on the role of scale in environmental history—exploring early modern ideas of the flood on local, national, transnational, and global scales. Barnett argues that the search for evidence of a universal flood collapsed early modern Europeans’ conceptions of time and space and reflects prominent scholars’ acknowledgment of the human capacity “to instigate geologic change on human timescale” (21).

In the first chapter, Barnett explores different dimensions of gender in early modern Europeans’ conceptions of the biblical flood. Scholars of this time would often cite the flood as the end of the Edenic period of Earth, during which men were giants who lived for hundreds of years and fathered many children. Thus, the flood epitomizes the era’s focus on the effects of sin on male bodies and masculinity. Barnett highlights the rather obscure work of Camilla Erculiani, the only woman known to have published a text on natural philosophy in Renaissance Italy. A Paduan philosopher and apothecary, Erculiani conceived of both supernatural and natural explanations of the biblical flood and suggested that the disaster’s moral implications apply only to men. Barnett argues that, paradoxically, Erculiani’s gender allowed her to voice controversial opinions about sacred texts during a time of religious persecution but also limited her ability to fully engage in European scientific communities.

Next, Barnett investigates the motivations behind the desire to globalize the flood—both in a geographical and a moral sense—as part of the European imperial project and Christian evangelism. Early modern Europeans fixated on reconciling a universal flood narrative with a perception of their own moral and racial superiority. Efforts to collect fossil evidence of a universal flood provided both Protestant and Catholic scholars a mode of participating in a diverse (though primarily European) exchange of fossils across the Republic of Letters, a transnational community of intellectuals. Barnett’s synthesis of scholarship on the Republic of Letters, the biblical flood, and European environmental consciousness demonstrates a unique approach, as it falls somewhere between environmental history and the history of knowledge.

Finally, the end of After the Flood returns full circle to Italy—where Erculiani was one of the first scholars to merge natural and supernatural explanations of the flood—to describe how scientist Antonio Vallisneri combined theories from Swiss Protestants and Italian Catholics to challenge English scholars and deemphasize a natural explanation for the biblical flood.

An expert of early modern European history, Barnett deftly weaves different European narratives of Noah’s Flood together over the span of a century and a half. Although beyond the scope of this text, Barnett’s analysis would benefit from a contextualization of the ways in which other forms of Christianity across the globe—such as the Egyptian Coptic Church and Ethiopian Orthodox Church—and other Abrahamic religions depicted Noah’s flood around the same time. Contrasting flood narratives between European and African Christians would yield more nuanced insights into Protestant and Catholic Europeans’ motivations for debating the scale and significance of the biblical flood, which Barnett herself acknowledges in her introduction. Furthermore, Barnett sometimes sacrifices broader accessibility of her book in favor of obscure Latin words and religious terms, potentially excluding readers less familiar with early modern Europe and Christianity. But overall, she has crafted a sophisticated argument with highly readable prose. After the Flood has wide appeal to historians and graduate students from different fields—such as geography, ecology, theology, gender studies—and deftly explores the intersection of these different disciplines.

Emily Cantwell is a Master’s in Global Policy Studies Candidate at the University of Texas at Austin’s LBJ School of Public Affairs.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.