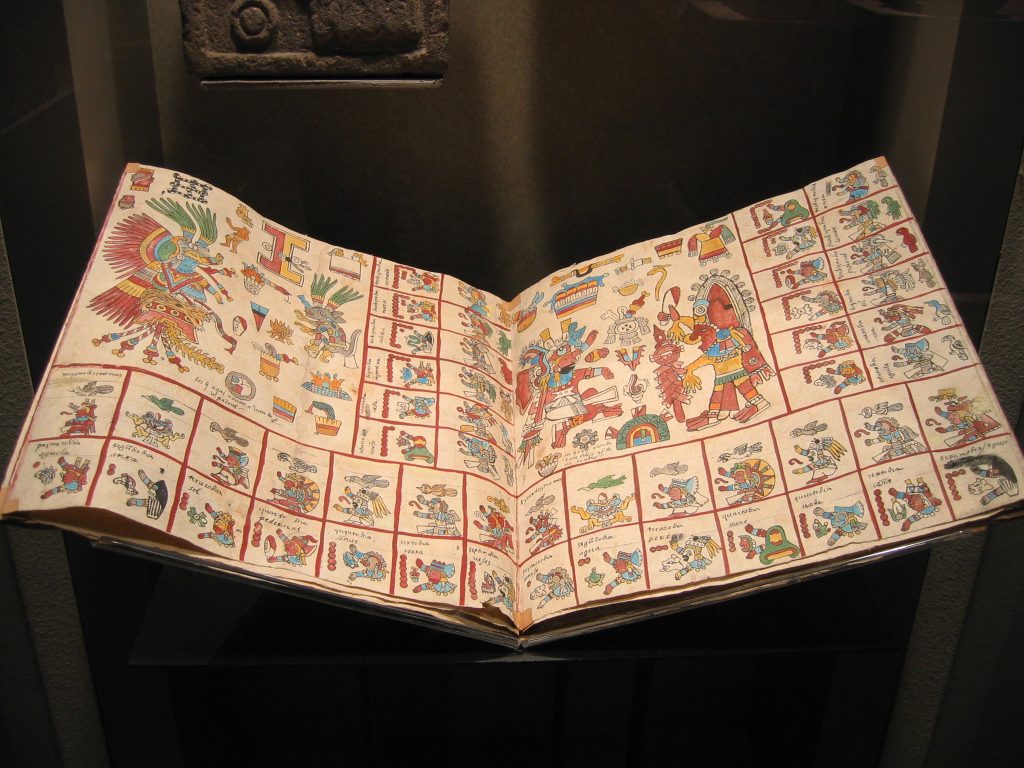

2021 marks the five-hundred-year anniversary of the fall of Tenochtitlan. The Aztecs, the arrival of the Spanish to the New World, and the clash of cultures that happened in Tenochtitlan on 12 August 1521 (in the Western calendar) have long captured the world’s attention. It has given shape to how we think of adventure, discovery, history, and time. It also taught humanity a valuable yet painful lesson: if societies do not document their histories, their memory is bound to disappear. When faced with this truism after all the plagues and wars, a small but important number of Aztec intellectuals born in New Spain wrote down the history of their people as it had been told and lived by their elders. They did so in the Nahuatl language and, as Camila Townsend argues, with the explicit intention of conserving Aztec memory. These documents are called the “Nahuatl Annals,” and they are the main source from which the history of this book is told. Townsend’s use of the Nahuatl Annals laid the foundation for a new history of the Aztecs.

The Nahuatl Annals tell the history of the Conquest and rely on Nahuatl sources for these narrations. Indigenous intellectuals, who had recorded their experiences with the intention of preserving Aztec history, wrote these sources. In doing so, they recollected Aztec memory by recording the voices of their elders and their communities both through narration and song and by placing them in dialogue with their new reality. Because these sources were written in Nahuatl, the intended audiences were Nahuatl speakers.

For Townsend, writing a new history of the Aztecs means two interrelated things. First, it means changing the analytical perspective from Spanish-language sources to Nahuatl-language documents. The latter, the author argues, have been neglected as non-reliable source materials, while the former has been exalted as the model for truth in this historical narrative. Furthermore, Nahuatl-language documents interpretation, relevance, and reliability has long been a subject of contestation. By using them to tell the story, Townsend makes an argument for their use as useful and reliable historical sources. She argues that they are valuable sources of information that contain coherent narratives of pre-conquest and conquest processes in Central Mesoamerica.

This is not an isolated scholarly insight, but rather is the result of a historiographical process of interpretation of Nahuatl-language sources that goes back to the mid-twentieth century. Fifth Sun engages fully with debates on how to understand the sources in “their own terms” alongside the arguments presented by the school of New Philology. Ultimately, the book functions as a call for historians of Mesoamerica to translate and transcribe their sources themselves. Second, Fifth Sun aims to broaden the readership of Aztec history without overwhelming the non-specialist public with historiographical and highly technical debates on how to approach the sources. Instead, the author leaves room for the interested reader to approach this metadiscourse in the footnotes or in the superb Appendix “How Scholars Study the Aztecs.”

Anyone who has read Townsend’s work knows that she is, above all, a very talented writer. Fortunately for all of us, Fifth Sun proves to be another beautifully written publication that keeps her readers engaged with the story from beginning to end. Each chapter begins with a small, fictionalized vignette that opens the way to the history encapsulated within each of the book’s ten chapters. As I heard her explain in a graduate zoom-course this semester, (one of the truly valuable things of zoom-graduate-school) these descriptions flow from her imagination but have a material basis in the repertoire of sources the author has read. Given that the objective of the book is to make public history socialize this strategy proves to be successful. Townsend’s style of writing history allows her to present the voices of the individuals she has encountered in the sources with a fuller narrative body, inviting readers to find and seek representation in the humanity of these historical characters.

This invitation extends to the historically contingent experiences of women. This episode holds an important place in how western thought conceptualizes its historical time. However, due to the highly militaristic, and political approach to its study, the telling of this history has overwhelmingly been told through the actions and participation of masculine figures. In the mainstream writing of this history, “la Malinche” appears as the only female character of this episode only because her role was undeniable fundamental to the process of conquest. However, and as has been documented in relation to Hernán Cortes, attempts to erase her from the sources were made. “Some later said it was a woman who first saw them and shouted aloud, sounding the alarm” (117), Townsend writes when describing the escape of Cortés from Tenochtitlan the night of the 1st of July of 1520, a night remembered in history as la noche triste. When highlighted, small episodes, such as this one, reframe the readers appraisal of the social composition of Aztec society and of the active participation and involvement of women throughout the process of conquest. We, like the author, can now hear the voice of this anonymous Aztec woman living in Tenochtitlan bursting through the pages of history, a history that had erased her.

Throughout Fifth Sun, the reader will encounter both small interventions like this and larger examples of participation of women’s participation. This emphasis on women’s roles gives a refreshing and most needed additional dimension of analysis to one of the most studied historical episodes in history. Furthermore, through these women and gender history perspectives, Townsend engages deeply with sexual and social relations and the problems that the change in paradigm brought on, such as the highly contested debates and confrontations around the issue of monogamy and polygamy. The reader will also find information on the history of homosexuality in Aztec culture—an overlooked (or ignored) subject.

Townsend explains that her book explores the tension between those who argue that the contemporary reader is trapped in their own particular anachronistic positionality and can never fully interact with the past, be it because of the language of the sources or because of the passing of time itself; and between those who argue that, in the end, and no matter our differences, we are all humans after all. If this is true, the argument goes, by reading the sources in their own language and relating to historical people in this way, some part of their persona can be reincarnated through the written word. The author aligns her research along the lines of the latter point. Thus, her ultimate goal is to vivify these characters and their histories from a different and as yet untold perspective that embellishes their existent multiple facets with new historical contour. Fifth Sun makes a big historical argument on the uses of sources and on the way to write history while remaining accessible to the general public. No doubt, Fifth Sun sets the bar very high, and its method should be replicated.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.