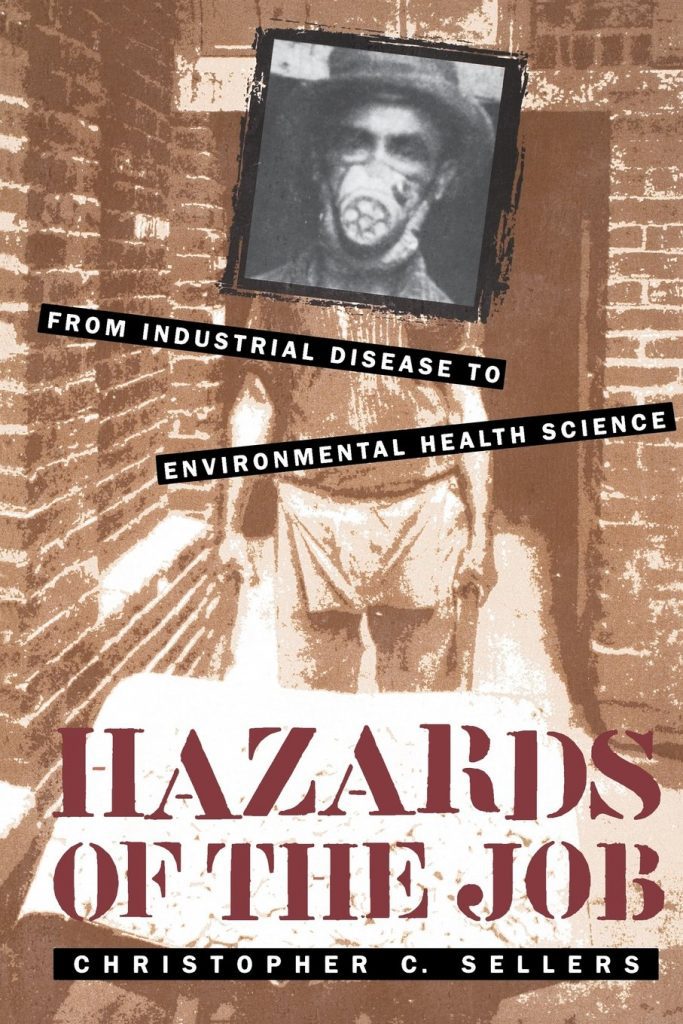

In Silent Spring, Rachel Carson pioneered the public discussion of the dangers of toxic substances present in the environment as a result of industrial activity. Christopher C. Sellers investigates the type of scientific knowledge about toxic substances that Rachel Carson built upon and popularized in this famous study. The book follows the development of industrial work-related illnesses from the 1890s through the early 1950s. First understood as “bodily idiosyncrasies” (28) that were outside the main concern of employers, or that should be endured by masculine workers, knowledge about occupational disease underwent significant transformations over the course of the early 20th century.

Sellers’ work is tightly woven and tracks multiple factors that contributed to the development of environmental health science. First, his work follows a series of key studies across the American industrial landscape: phosphorus poisoning from match factories, lead poisoning from a number of industries, silicosis from mining, radium poisoning from watch-making, and others. These demonstrate the slow development of the objects of study for this field. His study also traces changes in who had the expertise and authority to comment on the underlying causes of the illnesses, who should bear the brunt of these diseases, and the impact that this kind of medical science had for both industry, the medical profession, the state, and the lives of workers. Among the many scientists that Sellers writes into the history of environmental health science, Alice Hamilton stands out as a key advocate for the social (and political) purpose of the field and its development. Her work is important even if other contemporary physicians (such as David Edsall at the Harvard Division of Industrial Hygiene) overlooked it because it did not meet their standards for depoliticized science.

The scope of the book is clearly-defined and the chapter sequence is well-structured. Sellers frames the presentation of his research with a question containing an easy touchstone for anyone interested in environmental humanities and environmentalism: where did Rachel Carson’s knowledge of toxins come from? Sellers starts his narrative with the 1893 Chicago exhibition, by drawing our attention to the lead that was present in much of its white paint. The book is presented with a great deal detail, which makes for a somewhat slower read, but the subject necessitates the slow, methodical weaving he sets out to do.

Sellers is writing about the nature of the production of knowledge, and the implications that it had for industry, American public policy, and medical education. Even if he doesn’t specifically highlight the voices of the workers, Sellers’ work illuminates what the stakes were them. Many industrial workers distrusted the physicians who examined them, for they could be deemed unfit to work, thus hampering their chances to earn a living. When he does return to Carson’s work towards the end of the book, it is easy to understand her work as inheriting this rich history.

Sellers’ work is unique in that it first brought together medical and environmental history. In the wake of Hazards of the Job, a number of other studies of the environmental and health impacts of economic activity have followed, including Michelle Murphy’s Sick Building Syndrome and the Problem of Uncertainty: Environmental Politics, Technoscience and Women Workers (2006); David Naguib Pellow’s Garbage Wars: The Struggle for Environmental Justice in Chicago (2004); and Geoffrey Tweedale’s Magic Mineral to Killer Dust: Turner & Newall and the Asbestos Hazard (2000).

Within the fields of Environmental history and the History of science, Sellers’ book makes another key historiographical intervention. Given that industrial diseases could not be studied only in the laboratory because a) their cause wasn’t always known and b) often it was a combination of environmental factors along with the pollutants themselves which produced the illness, the type of medical and environmental knowledge produced required study in industrial settings. In this regard, the early industrial work-place was neither a “field”, such as we might find in environmental histories of particular geographic regions, nor “the laboratory”, in the case of a specific type of invention or discovery.

Beyond these two fields, Sellers makes wider contributions. By looking at the specific hazards that workers were exposed to, his work contributes to histories of labor, as well as histories of public health as it outlines specific tensions between medical education and industrial activity.

When we eventually meet Rachel Carson’s book, as the book draws to an end, we are able to understand not only the specific historical processes that resulted in increasing knowledge of toxins like DDT, but also the peculiar relationships of research between industry and health professionals. These research activities served to confirm the “benignity” (232) of American commodities in the latter part of the 20th century. This helps the reader understand, for example why even though knowledge of lead poisoning was common, leaded gasoline boomed in production until its eventual-phase out in the 1970s.

Ultimately, Sellers’ book is a valuable contribution to multiple fields and there is much within it that can be mined depending on one’s interest. It is a a challenging but rewarding read for anyone interested in the history of environmentalism.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.