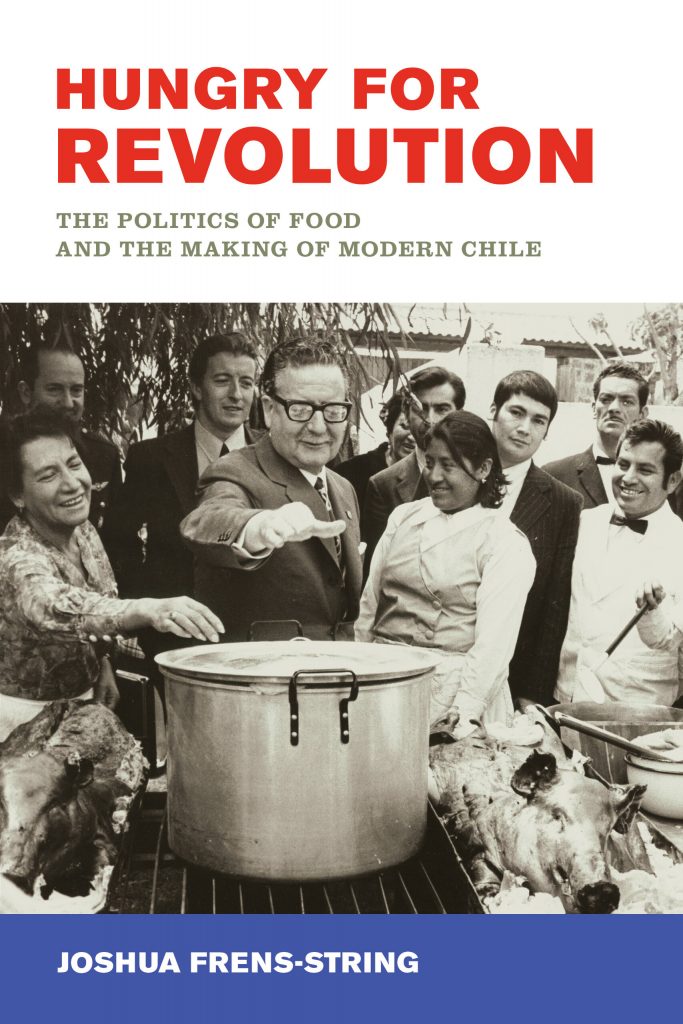

More than fifty years ago, Chile began a democratic path toward socialism with the election of Salvador Allende. President Allende promised that the country’s revolution would taste of “empanadas and red wine.” These quintessentially Chilean staples represented his pledge to ensure social welfare. In Hungry for Revolution: The Politics of Food and the Making of Modern Chile, historian Joshua Frens-String explores this relationship between revolutionary politics, food security, and nutrition science in twentieth-century Chile. He concludes that the Allende years signified the culmination of decades-long popular struggles to position food security as a basic right of democratic citizenship.

Over seven chronological chapters, Frens-String weaves together political, social, and economic history to reveal how Chile’s food system reflected larger inequalities within society. The book’s first two chapters chronicle the rise of workers’ organizations in the urban capital of Santiago and the mining camps of northern Chile. Despite distinct economic contexts, both regions grappled with high prices and food shortages. Frens-String uses profiles of individual labor organizers to drive the narrative. He shows that these actors identified hunger as clear evidence of working-class exploitation and demanded popular access to dietary staples. Through decades of campaigns against the rising cost of living, Chilean workers made it clear that food security was central to a functional national economy.

In chapters three and four, Hungry for Revolution shifts the focus from the streets to the halls of government offices. This section traces how state actors responded to the left’s politicization of food. In particular, Frens-String’s attention to gendered ideas is a significant strength of these chapters. Government officials, social scientists, and medical doctors often blamed mothers for poor nutritional outcomes. Thus, educational outreach targeted poor and working-class women. Public health officials in the 1940s offered cooking classes and consumer handbooks to teach new food preparation methods and to encourage new eating habits. In the countryside, the state urged rural women to participate in agrarian reform by embracing sacrifice and frugality. Government officials pushed women to plant small family gardens, preserve their own vegetables, and switch to composting to conserve scarce fertilizers. The state’s focus on female consumers in its efforts to alter Chile’s nutritional habits reflected gendered beliefs about work and domesticity.

The concluding chapters of Hungry for Revolution demonstrate that state intervention in food production and distribution fueled both a socialist revolution and a far-right counterrevolution in the 1960s and 1970s. Rural landowners, urban merchants, and female consumers rejected the government’s interference in their decisions to produce or consume certain foods. As food demand outpaced supply, the Allende government encouraged consumers to replace traditional staples, such as red meat, with unconventional substitutes, like merluza fish. The state’s failure to ensure consumer abundance led to anxiety and frustration, which the opposition harnessed to demand an end to state intervention. Rising social unrest would pave the way for the military coup that overthrew Allende in 1973, which in turn led to the dismantling of the Chilean welfare state.

Hungry for Revolution is a fascinating account of national development in twentieth-century Chile. Using food politics as a lens into larger debates about what democratic states can and should provide their citizens, Frens-String traces how Chileans came to see food security as a basic right of citizenship. He illustrates that popular mobilization around consumer issues furthers our understanding of social welfare and economic justice. This book will appeal to historians of modern Chile as well as food historians. However, Hungry for Revolution offers insight to scholars broadly interested in national development, democratization, and social welfare in the Americas.

Gabrielle Esparza is a fourth-year Ph.D. candidate at the University of Texas at Austin. She is a historian of Latin America with a focus on twentieth-century Argentine history. Her current research interests include democratization, transitional justice, human rights, and civil-military relations. Gabrielle holds a B.A. in History and Spanish from Illinois College and received a Fulbright English Teaching Assistantship to Argentina in 2017. At the University of Texas at Austin, Gabrielle has served as a graduate research assistant at the Texas State Historical Association and contributed to the organization’s Handbook of Texas. She served as co-coordinator of the Symposium on Gender, History, and Sexuality in 2020-2021. Currently, she is the Associate Editor of Not Even Past.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.