Sacred Hunger, a novel by Barry Unsworth (which was awarded the 1992 Booker Prize) is the story of a single ship and a single voyage.  The novel begins in 1752, in Liverpool, England. The Royal African Company, a chartered corporation created in the mid-17th-century with a monopoly on trade with the African coast, has just lost the last of its privileges, making the slave trade, for the first time, a “free trade” (all irony intended). Inspired by the promise of lucrative profits, a Liverpool merchant, William Kemp, commissions the construction of a ship to engage in the newly opened trade. Before the ship sets sail, Kemp engages his nephew, Matthew Paris, a disgraced apothecary, to serve as the ship’s surgeon.

The novel begins in 1752, in Liverpool, England. The Royal African Company, a chartered corporation created in the mid-17th-century with a monopoly on trade with the African coast, has just lost the last of its privileges, making the slave trade, for the first time, a “free trade” (all irony intended). Inspired by the promise of lucrative profits, a Liverpool merchant, William Kemp, commissions the construction of a ship to engage in the newly opened trade. Before the ship sets sail, Kemp engages his nephew, Matthew Paris, a disgraced apothecary, to serve as the ship’s surgeon.

In the scales of Kemp’s complacent morality, his good deed in “saving” Paris, will be amply repaid in the healthier and more valuable slaves that his ship will be able to sell once it reaches America. This fictional view closely mirrors that of Thomas Jefferson, who once wrote that masters who spared pregnant slave women from field labor were wise as well as kind, for “a child raised every 2 years is of more profit than the crop of the best laboring man.” To Jefferson, this happy equation revealed the hand of an enlightened creator in making “our interest and our duties coincide perfectly.”

In the chapters that follow the ship’s arrival on the African coast, Unsworth vividly and accurately describes the painstaking and painful process by which a slave ship “made” a cargo in the mid-18th-century. The climax of Sacred Hunger occurs during the “middle passage” when slaves, sailors, and Paris combine to mutiny and seize the ship in mid-Atlantic. (That slaves might take control of a slave ship at sea draws upon several historical precedents.) The mutineers do not attempt to sail back to Africa, but rather steer the course later taken by the men who mutinied against Captain Bligh on the HMS Bounty in 1789. They try to escape recapture by sailing “off the map,” and build a new society in an uncharted region, deep in the Florida Everglades.

Once in Florida, Jimmy, the African “linguister,” brought on board the slave ship to communicate with the enslaved, puts his story-telling skills to work to weave the fledging camp of ex-slaves and ex-slavers into an “imagined community” with a shared identity and purpose. Paris, while acknowledging the importance of this task, also recognizes it as a process of myth-making. Jimmy’s oft-told history of the mutiny, the community’s founding legend, “ran like a clear stream” with a straight-forward causality, and clear moral purpose. In keeping with his role as the community’s “moralist” (and historian), Jimmy “omitted” or “even falsified” “certain aspects” of the past. This historical “morality play” starkly contrasts with the more ambiguous, “viscous substance of truth,” that Paris peers into when he tries to recall the actual event. When questioned by his young son (born in Florida to an African wife) about the contrast between “what really happened” in the past and how it has been remembered (or retold) Paris answers simply: “Nobody sabee de whole story.”

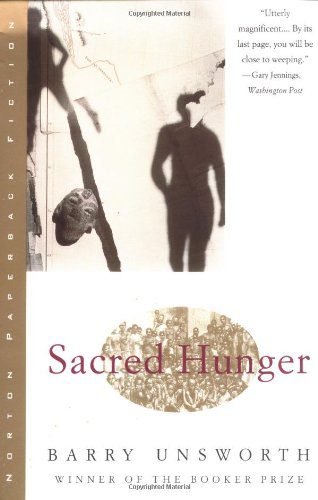

Sacred Hunger similarly weaves together the real and the fictive. For instance, the incident that sparked the mutiny follows closely upon the actual (and infamous) case of the slave ship Zong in 1781, in which sickly slaves were deliberately cast overboard so as to collect upon their insurance value as cargo “lost at sea.” However, in other places, Unsworth subtly alters or inverts the historic record, drawing a fictional curtain across the facts, perhaps to deliberately cast doubt upon the veracity of historical “truths.” Nicolas Owen, an Irishman who kept a journal of his life as a slave-dealer on the Sherbro River in West Africa in the late 18th-century, becomes in the novel, Timothy Owen, an Englishman. However, the factual Owen’s callous disregard for the human cost of the trade is echoed by his fictitious doppelganger. Similarly, Timothy’s foreboding sense of death in the novel mimics the actual death of Nicolas in Africa in 1781.

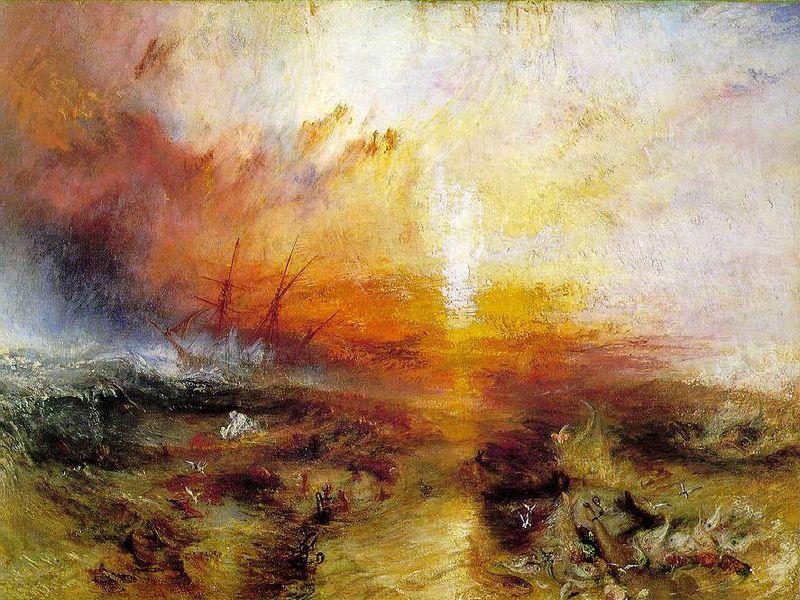

A nineteen century painting captures the brutality of the 1781 Zong slave ship massacre

In the novel, the mutineers’ Everglades community, “‘where white and black live together and no one is chief,’” reaches a crisis during a “palaver,” or public trial. Watching the trial, Paris realizes that regardless of the outcome, the accused, a man named Iboti, will be sentenced to some form of servitude, either permanently enslaved to his accuser if convicted, or if acquitted, temporarily bound to labor for his “attorney” in payment for his services.

Given the community’s origin, Paris expresses dismay at its members’ willingness to countenance the reemergence of human bondage. In response, Iboti’s accuser, an ex-slave named Kireku, calls Paris a fool. “I no ask come here. Now I here, I fight for place,” Kireku declares. Kireku proffers a version of Adam Smith’s (not yet written) Wealth of Nations in pidgin creole (that also echoes and mocks the opening chapter of the novel, when Liverpudlians eagerly anticipated the profits they would make from a free trade in slaves): “Strong man make everybody rich. Everybody dis place happy an’ rich come from trade. Some man not free, nevermind, buggerit, trade free.”

Unsworth presents Paris’s own quest for knowledge as intellectual hubris or worse. It was his arrogant “insistence on [promulgating his own] opinion, concealed under the appearance of a desire for truth” which led him to publish the “blasphemous” ideas about the age of the earth that brought about his disgrace and the death of his wife and child. Despite this abject lesson, Paris continues to try to impose his ideas upon others. Kireku dismisses Paris’s egalitarian ideals as mere intellectual colonialism. Nadri, a man with whom Paris shares a wife, accuses him of wanting everyone to “serve some idea in your head” and of “all the time wanting to make some kind of laws for people.” When Paris protests that arguing “from particular truths to general ones” is a basic rule of reason, Nadri counters, “Partikklar to gen’ral is [the] story of [the] slave trade.”

Since morality and other kinds of “law” cannot be separated from self-interest, the novel ultimately rejects the moralizing and truth-making project itself. While Paris belatedly realizes that his attempt to engage in a “moral argument” with Kireku was a mistake, Unsworth presents Nadri’s “constitutional unwillingness to generalize about human behavior” as form of wisdom.

Like the post-modern theorist Michel Foucault (whose influence in the Anglo-phone world was peaking at the time of the novel’s publication), Unsworth portrays the pursuit of knowledge as intrinsically intertwined with the creation and exercise of power. In his own work, Foucault argued that since the mid-18th-century Enlightenment, western society’s inquisitiveness has worked in tandem with its boundless acquisitiveness and desire to dominate. In the character of Matthew Paris, Unsworth offers us an anachronism: an early-modern protagonist who acquires the post-modern insight that truth-making is itself a form of control and who becomes aware of his complicity in an oppressive system without having any intellectual, metaphysical, or religious beliefs upon which to build any alternative. In the final pages of the novel, as he lies dying, Paris dimly recognizes that “doubt is the ally of hope, not its enemy, and . . . [this was] all the blessing he had.”

Picture credits:

Joseph Mallord William Turner, “Slavers throwing overboard the Dead and Dying — Typhoon coming on”

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston via Wikimedia Commons