From the editor: As our thoughts turn back to teaching, Not Even Past turns back to some of our posts from 2013-14 about new and best teaching experiences. (August 15, 2014)

As the school year comes to a close, we end our series of monthly features on teaching history with a creative assignment devised by one of our US History professors. Instead of assigning only written or oral work, Robert Olwell was one of a handful of History faculty who asked their students to make video essays on specific topics related to the course. On this page, Olwell tells us about the assignment and we include some of the best of the videos his students created. Below we link to the instructions Olwell gave to the students. And throughout the month of May, we will post video essays our students produced in other History Department courses. (May 1, 2014)

In the fall of 2013 I taught the first half of the US history survey course (HIS 315K), which offers a treatment of the major themes of American History from 1492-1865. There was nothing unusual in this. I have taught 315K at least once a year (and often twice) since I came to UT twenty years ago. The course is designed as a lecture course, with assigned readings, and four in-class essay exams. The enrollment is generally 320 students. This time however, my enrollment was capped at only 160. The relatively small number allowed me to conduct a pedagogical experiment. In addition to their individual written essay exams, I assigned each of my students the task of working with three classmates to create a short “video essay.” Their task might fairly be described as a producing a brief research report in which they present their findings not on paper but on the screen. My hope was to enlist students’ familiarity and fascination with digital media in the cause of history and pedagogy.

In order to keep control of the project, I made several command decisions. First, I divided the class into forty teams of four students each. I allowed students no choice of partners but simply used the class roll and the alphabet to make the groups (hence team members’ last names often start with the same letter). Second, I gave the groups no choice as to their topic. I created a list of forty topics that I deemed suitable (i.e., could easily be presented in a four-five minute video) and assigned one topic to each group.

As the rubric that I posted for the assignment indicates, by far the most important part of their task was the first one: writing the “script.” In late October, my Teaching Assistants and I poured over the forty, ten-page- long scripts. (Each TA looked at ten scripts and I looked at all of them.) Our aim was to offer historical critiques and suggestions, and to make sure the students were on the right track as regards sources, bibliography, and so on. We acted more as “historical consultants” to their projects than as producers. Having never made or posted a video myself, I could offer them little or no assistance in that regard. Instead, I relied on the students’ own facility with visual and digital media to carry them through. (Having watched my two teen-aged daughters produce videos both as school projects and for fun, I rightly suspected my students would be more than capable of fulfilling this part of the assignment on their own.)

Overall, I would judge the “video essay” project to have been a great success. In their peer evaluations most students agreed; some wrote that it was the most interesting thing they had ever done in a history class. The standard of the finished videos was quite high (the average grade was a B+). There were some difficulties, of course. Some of the groups did not work well together and some students did not pull their weight. The final part of the assignment, peer evaluation, was included to address this possibility. However, most groups did cooperate effectively and I used the peer evaluations as often to reward those students acknowledged by their teammates to have been project leaders, as to punish the slackers.

Would I do it again? Yes, but. Next time, I would probably make the project optional (perhaps replacing one of the written exams), and allow students to make their own teams and choose their own projects.

Here is the assignment sheet and rubric that I handed out to the students.

And here are the six video essays that I deemed the best of the forty produced by my students last fall.

Cahokia

By Valerie Salina, Jeffrey A. Sendejar, Victor Seth, and Sharmin Sharif

The 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment (1863-65)

By Madeline Christensen, Nathan Cliett, Rebecca Coughlin, and Corbin Cruz

Anne Hutchinson

By Justin Gardner, Rishi Garg, Yanni Georghiades, and Rachelle Gerstner

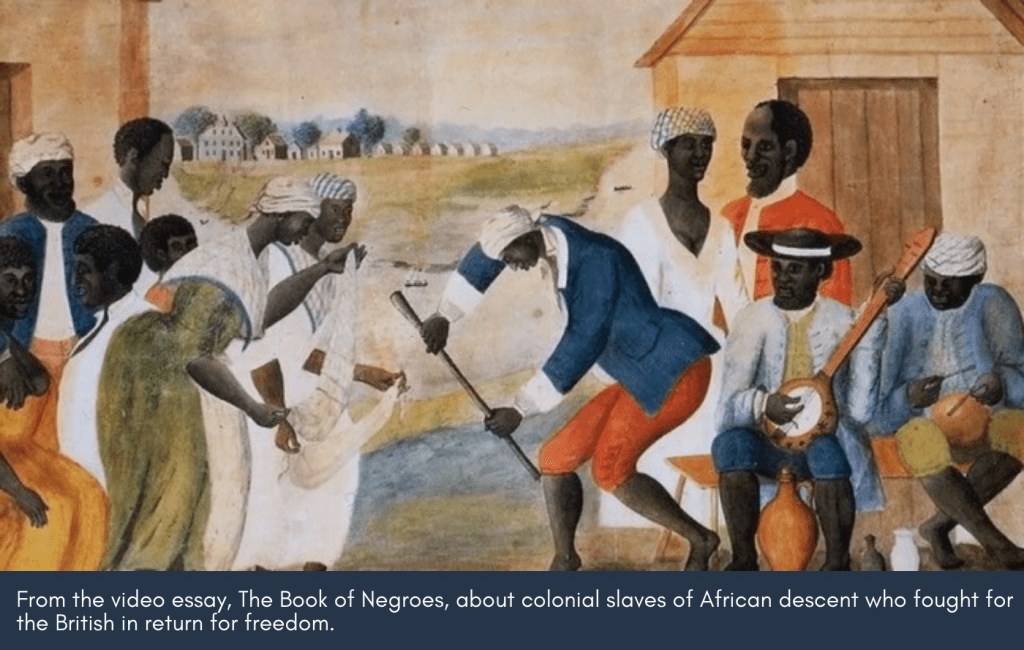

The Book Of Negroes

By Will Wood, Anfernee Young, Qin Zhang, and Sally Zhang

Dr. Josiah Nott

By Salina Rosales, Felipe Rubin, and Hunter Ruffin

New Amsterdam

By Evan Taylor-Adair, Oliver Thompson, Kimberly Tobias, and Reynaldo Torres Arellano

Watch for more student videos in the coming weeks.

In the meantime, revisit Blake Scott’s examination of the coming of tourism to the Panamanian rain forest: I am Tourism/Yo soy Turismo

And check out other stories on teaching and learning:

Also by Robert Olwell, You Say You Want a Revolution? Reenacting History in the Classroom

Video assignments by Jacqueline Jones, Students Debating History: Another Look at the Video Essay