Munich’s central square, Marienplatz, is best known today for its magnificent Rathaus-Glockenspiel that delights tourists and townspeople alike with its melodies. But until the nineteenth century, the square’s main attraction was a golden pillar adorned with the Virgin Mary known as the Mariensäule. Still standing today, the Mariensäule is a reminder of the religious reformations Bavaria endured as well as the Bavarian state’s early attempts at centralization and modernization in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Erected in 1638 by order of Elector Maximilian I of Bavaria to thank the Virgin for protecting the city from an attack by Protestant Swedes during the Thirty Years War, the Mariensäule not only represented Maximilian’s fervor for Catholicism, but, as Ulrike Strasser writes, also represents his use of “virginity as a master metaphor to elaborate ideas about good governance and a functioning society.” Usually used to imply innocence, purity, and occasionally frailty, images of virgins and virginity were among Maximilian’s strongest metaphorical tools. State of Virginity explores how Maxilimilian employed female virginity to increase patriarchal power and limit female agency and facilitate Bavaria’s centralization.

Drawing on a wide variety of archival documents including Bavarian laws, civil court records, ecclesiastical court documents, and select convents’ records, Strasser investigates the ways in which marriage, family organization, and female religious life changed as a result of the new emphasis placed on virginity as the female moral and political ideal. Strasser explains that judicial records are useful to her study because they show how individuals explained their own behavior, emotions, and identities under the eye of powerful institutions. These records permit her to observe the state or the church at work, and to see how people reacted to mandates from above.

Starting with an examination of Bavarian marriage, Strasser notes that people explained their attitudes toward marriage and sexuality in the context of competing religious and secular judicial discourses. The Catholic Church wished to have all couples marry, regardless of social status, in order to affirm their respect for the sacrament in marriage and avoid licentious behavior. The state, on the other hand, took a rather paradoxical approach to marriage with its establishment of Munich’s marriage bureau. Of the utmost importance to the marriage bureau was a bride’s virginal status. If a woman was not a virgin, the union was unlikely to be approved by the marriage bureau. The state saw this virginal prerequisite to marriage as a way to prevent poor people from procreating outside of marriage, and reduce sexually licentious unions. However, in addition to virginal status, the marriage bureau also scrutinized the financial stability of couples. On top remaining chaste, the prospective spouses also had to prove they were capable of providing for a family. For the poor couples, this was often difficult to achieve. Therefore, the creation of the bureau resulted in marriage becoming a type of social status reserved for the upper echelons of society.

Starting with an examination of Bavarian marriage, Strasser notes that people explained their attitudes toward marriage and sexuality in the context of competing religious and secular judicial discourses. The Catholic Church wished to have all couples marry, regardless of social status, in order to affirm their respect for the sacrament in marriage and avoid licentious behavior. The state, on the other hand, took a rather paradoxical approach to marriage with its establishment of Munich’s marriage bureau. Of the utmost importance to the marriage bureau was a bride’s virginal status. If a woman was not a virgin, the union was unlikely to be approved by the marriage bureau. The state saw this virginal prerequisite to marriage as a way to prevent poor people from procreating outside of marriage, and reduce sexually licentious unions. However, in addition to virginal status, the marriage bureau also scrutinized the financial stability of couples. On top remaining chaste, the prospective spouses also had to prove they were capable of providing for a family. For the poor couples, this was often difficult to achieve. Therefore, the creation of the bureau resulted in marriage becoming a type of social status reserved for the upper echelons of society.

By making the prerequisites of marriage so strict, Bavarian authorities required women to “uphold the boundaries of a new social and sexual order” that made virginity a moral obligation, among both upper and lower classes. When wealthy women remained chaste, their families’ economic interests and possible alliances with other wealthy families remained intact, benefitting both the families and the state, which relied on these families for money and support. When women from the lower sorts remained chaste, the state believed the number of illegitimate children and single mothers would greatly decrease. This would also further strengthen the patriarchal household that the Catholic state viewed as being essential to an orderly and stable society. Although virginity became the female moral and political ideal, as Strasser argues, that was often difficult for women of the lower sorts to achieve. With marriage being denied to poor couples, these couples entered into nonmarital sexual relationships that were not sanctioned by the state. Strasser hints that the “perpetual state of virginity” that the state advocated for women who were denied marriage by the bureau, was simply an unrealistic goal. One of the only institutions that guaranteed a perpetual state of virginity for women was a convent. However, just like marriage, in the seventeenth-century, Bavarian cloisters turned away poorer women and increasingly became depositories for elite, unmarried women. Though groups of unmarried, uncloistered virgins, like the English Ladies, were established, they too consisted of “honorable women,” meaning those from the upper-middling classes or the elite. Although poor women may have remained chaste, the Bavarian state began to view unmarried and uncloistered poor women, regardless of their individual virginal status, as a “social and sexual threat” to the Bavarian state.

By making the prerequisites of marriage so strict, Bavarian authorities required women to “uphold the boundaries of a new social and sexual order” that made virginity a moral obligation, among both upper and lower classes. When wealthy women remained chaste, their families’ economic interests and possible alliances with other wealthy families remained intact, benefitting both the families and the state, which relied on these families for money and support. When women from the lower sorts remained chaste, the state believed the number of illegitimate children and single mothers would greatly decrease. This would also further strengthen the patriarchal household that the Catholic state viewed as being essential to an orderly and stable society. Although virginity became the female moral and political ideal, as Strasser argues, that was often difficult for women of the lower sorts to achieve. With marriage being denied to poor couples, these couples entered into nonmarital sexual relationships that were not sanctioned by the state. Strasser hints that the “perpetual state of virginity” that the state advocated for women who were denied marriage by the bureau, was simply an unrealistic goal. One of the only institutions that guaranteed a perpetual state of virginity for women was a convent. However, just like marriage, in the seventeenth-century, Bavarian cloisters turned away poorer women and increasingly became depositories for elite, unmarried women. Though groups of unmarried, uncloistered virgins, like the English Ladies, were established, they too consisted of “honorable women,” meaning those from the upper-middling classes or the elite. Although poor women may have remained chaste, the Bavarian state began to view unmarried and uncloistered poor women, regardless of their individual virginal status, as a “social and sexual threat” to the Bavarian state.

With marriage, family, and the convent all becoming elite institutions, what happened to the unmarried, poor, virginal woman? Are we to believe that she merely succumbed to “the sins” of the lower sorts and entered into profligate relationships? Strasser suggests, without much evidence, that the new marriage regulations and convent restrictions may have strengthened the state’s control over noble society but actually led to more relationships outside of marriage among the lower classes. Despite this lack of evidence, State of Virginity is an innovative piece of scholarship. Other studies have focused solely on the impact that this new “virginity” had on women’s experiences, but while Strasser does include the effects on women, her most poignant arguments explain how the state’s regulation of virginity brought about changes in societal structure, specifically the centralization of the Bavarian state. State of Virginity successfully repositions the role of the female sexualized body as a factor in the strengthening of Bavarian patriarchy and the process of state building under Maximilian I.

Photo Credits:

Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria, with his wife Elisabeth Renée of Lorraine, 1610 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

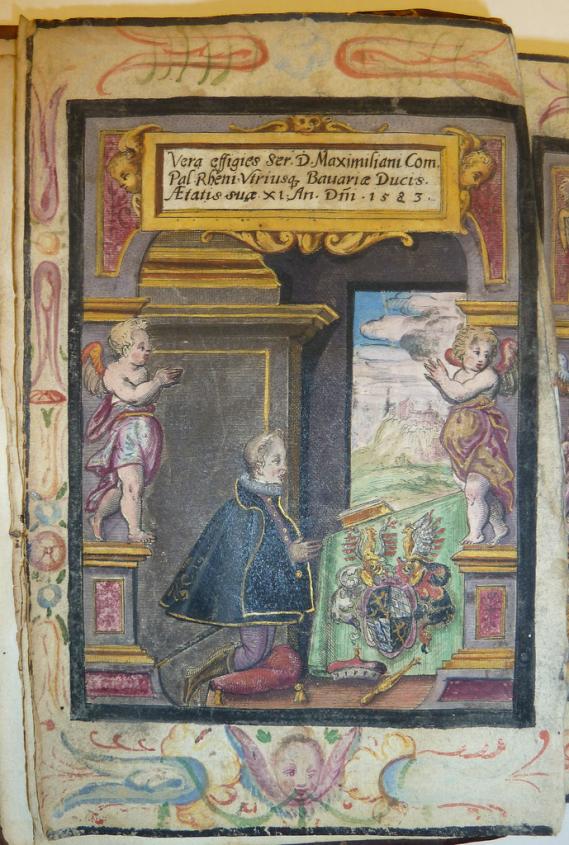

Hand colored illustrated of Maximilian I at the age of 11 (Image courtesy of Penn Provenance Project)

Munich’s Rathaus-Glockenspiel (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

by

by