by Brian McNeil

Like most teenagers growing up in Alabama during the late nineties, my first encounter with the 1925 John Scopes Trial came on the first day of my ninth grade biology class.  Inside the front cover of the textbook a message from the Alabama State Board of Education stated: “This textbook discusses evolution, a controversial theory some scientists present as a scientific explanation for the origin of living things, such as plants, animals, and humans.” Passed by the Board of Education in 1995, the supplement went on to say, “No one was present when life first appeared on earth. Therefore, any statement about life’s origins should be considered as theory, not fact.”

Inside the front cover of the textbook a message from the Alabama State Board of Education stated: “This textbook discusses evolution, a controversial theory some scientists present as a scientific explanation for the origin of living things, such as plants, animals, and humans.” Passed by the Board of Education in 1995, the supplement went on to say, “No one was present when life first appeared on earth. Therefore, any statement about life’s origins should be considered as theory, not fact.”

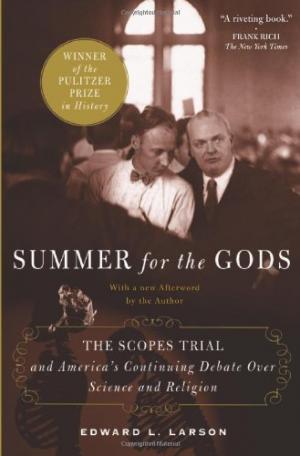

The disclaimer in Alabama biology textbooks was the product of a decades-long debate in the United States over science and religion in the classroom. In Summer for the Gods, Edward J. Larson examines this oft-contentious dispute from Darwin to Darrow to Dayton—host of the Scopes Trial and present home of Bryan College, one of the leading institutes of creationist biology. He demonstrates how contemporary thought influenced the debates surrounding the Scopes Trial and, in the last section of the book, how dramatic portrayals such as Inherit the Wind shape our own thinking on evolution today. Yet, as Larson skillfully notes, the “Trial of the Century” stays with us not because of the scientific questions it raised but because the Scopes Trial embodied “the characteristically American struggle between individual liberty and majoritarian democracy.” The Scopes Trial, in other words, asked who would control curriculum in classrooms? Would it be the local many that clung fast to their bibles and looked up to the heavens for the answer to the origin of man? Or, would it be the distant few who studied science and looked down into the earth at the fossil record for the answer to the origins of species?

These are the questions that drew the major antagonists to the Scopes Trial: William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow. Bryan—known as the Great Commoner for his support of the Populist Party in the 1890s—was a reformer who steadfastly held to religion and popular politics. Darrow, the most prominent lawyer in early twentieth-century America, used his sharp legal mind to challenge popular notions of morality and religion. The most memorable aspect of the trial was the back and forth between these two American giants on the lawn outside the courthouse (the trial had to be moved outside to accommodate the interested public). Darrow asked questions that had nothing at all to do with human evolution and everything to do with casting doubt over Evangelical Christianity in general and Bryan’s faith in particular. “Did you ever discover where Cain got his wife?” Darrow asked at one point during Bryan’s testimony. “No sir; I leave the agnostics to hunt for her,” the Commoner acidly replied.

The great strength of Summer for the Gods is Larson’s ability to demonstrate how the debate over science and religion has changed over the decades. As unbelievable as it may sound today when the battle lines are so firmly demarcated and the trenches are so deeply dug, there was a time when fundamentalist Christians attempted to accept evolutionary biology on its own terms. The first section of the book details how this era of good feelings changed following the end of the First World War. Believing that modernism, natural selection, and eugenics caused both the Great War and the social unrest that followed it, fundamentalist Christians fought back against evolutionary biology. Because of this rising tide of conservatism, many states in the early 1920s passed laws that restricted teaching Darwinism in the classroom and ultimately led to the Scopes Trial.

I currently live in Texas, and the great debate in the Lone Star State over curriculum in the classroom has in many ways shifted away from science toward social studies and history. Conservatives and Progressives are now debating the origin and character of the United States, not the origin of human beings. But if Larson were to comment on this dispute over history textbooks, he would surely argue that the debate is not new at all. Instead, he would insist that the same struggle between majoritarian democracy and individual liberty that guided the Scopes Trial frames the present debate over history textbooks in Texas. Larson’s lucid writing, command of detail, and ability to connect the Scopes Trial to longstanding debates in American history make Summer for the Gods a great read.

Further reading:

A detailed description of the Scopes “Monkey Trial” via the University of Missouri School of Law.

The Washington Post on the current debates over history textbooks in Texas.