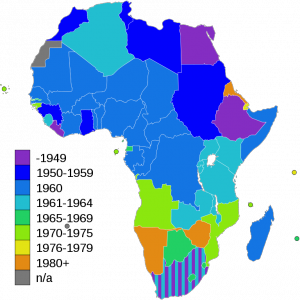

In the 1960s the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) emerged as a political ‘hot spot’ in Africa.  The transition from decades of Belgian colonial brutality and paternalism to independence, as historical records reveal, did not go smoothly. Gender and Decolonization in the Congo departs markedly from most work on this process by focusing on gender. There is a tendency on the part of scholars to neglect gender in their histories of decolonization in Africa. Political scientists, for instance, are apt to focus on the rise of the Cold War rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union. Much historical scholarship on the DRC shows enthusiasm for resolving puzzles arising from the perennial question: who assassinated Patrice Lumumba? Karen Bouwer delivers on her stated goal, to draw attention to Congolese women’s active role in the politics of decolonization. Overall, the study goes a long way toward presenting the first truly groundbreaking investigation of women’s political participation in the DRC.

The transition from decades of Belgian colonial brutality and paternalism to independence, as historical records reveal, did not go smoothly. Gender and Decolonization in the Congo departs markedly from most work on this process by focusing on gender. There is a tendency on the part of scholars to neglect gender in their histories of decolonization in Africa. Political scientists, for instance, are apt to focus on the rise of the Cold War rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union. Much historical scholarship on the DRC shows enthusiasm for resolving puzzles arising from the perennial question: who assassinated Patrice Lumumba? Karen Bouwer delivers on her stated goal, to draw attention to Congolese women’s active role in the politics of decolonization. Overall, the study goes a long way toward presenting the first truly groundbreaking investigation of women’s political participation in the DRC.

Bouwer illustrates women’s contribution to politics with a narrative woven around the life and popular representation of Patrice Lumumba. Bouwer privileges Lumumba’s legacy, writing, and personal experience not to glorify his image, but to expose the complex system of social and political relations that shaped Congolese women’s lives. This gendered analysis integrates a wide variety of evidence in a compelling manner, including Lumumba’s writings and speeches, literary works such as Aime Cesaire’s A Season in the Congo, and cinematic works dealing with Lumumba’s legacy. Of particular importance is the discussion of films produced by Haitian director Raoul Peck such as Death of a Prophet, Sometimes in April, and Lumumba.

Patrice Lamumba in his official portrait as Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1960. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Patrice Lamumba in his official portrait as Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1960. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

These critical assessments of film and literature are some of the strongest passages in the book. Equally interesting are the chapters that testify to the high level of women’s involvement in politics. These include the life portraits of frontline female politicians such as Leonie Abo, Andre Blouin, Pauline Opango, Martine Mandinga and Madeleine Mayimbi. In addition, the author brings into sharp focus the role of women as preservers of historical memory: we learn about efforts on the part of Leonie Abo to preserve the memory of the slain revolutionary, Pierre Mulele. We also learn about Justine M’poyo’s effort to preserve Joseph Kasavubu’s memory by all means necessary.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of this study lies in the fact that it offers a promising new approach to the history of decolonization in the DRC. It offers a valuable new perspective on interesting subjects such as the Kwilu Rebellion of 1963-1965 and Haitian migration to Congo. Decolonization in the Congo will be able to stir the minds of anyone interested in gender studies, history, politics, diaspora studies, development studies and literary studies. It presents rich documents including a useful index, an impressive bibliography as well as extensive notes and rare photographs of Congolese female activists.

Further reading:

King Leopold’s Ghost by Adam Hochschild recounts the grim history of Belgian rule in pre-decolonization Congo.

A 2002 interview with Pauline Opango.

The inhuman event of the 9/11 attacks and the upsurge in terrorism in the world have forced western countries, especially, the United States, to re-examine their relationship with Africa.

The inhuman event of the 9/11 attacks and the upsurge in terrorism in the world have forced western countries, especially, the United States, to re-examine their relationship with Africa.

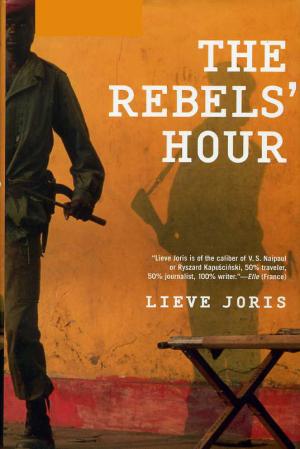

From this touchstone Joris recounts Assani’s life through a series of biographical flashbacks — from his youth as a cowherd in the turbulent Eastern Congo of the 1960s to his rise to generalship in a new Congolese state. Throughout, the reader is given a passionate and often disarming portrayal of the book’s scarred but loyal subject as he struggles with the complex ethnic and political dynamics at work in the frail but enduring Congolese state.

From this touchstone Joris recounts Assani’s life through a series of biographical flashbacks — from his youth as a cowherd in the turbulent Eastern Congo of the 1960s to his rise to generalship in a new Congolese state. Throughout, the reader is given a passionate and often disarming portrayal of the book’s scarred but loyal subject as he struggles with the complex ethnic and political dynamics at work in the frail but enduring Congolese state.