Bolivia in the Age of Gas by Bret Gustafson offers an analysis of debates on the political struggles over natural gas and the ways in which the management of this resource radically transformed Bolivia´s national politics. The book is a long-lasting history that begins in the 1930s with the extraction and commercialization of fossil fuels and takes the reader through turning point events like Evo Morales’s presidency in 2006, the construction of the gaseous state, and the reasons for its fall. Gustafson examines how the structural adjustment programs implemented by Bolivian middle-class elites in agreement with the United States created an economic model that only benefited a certain group of people. This can be perceived by how neoliberal political projects created by multinational corporations resulted in in state violence, repression, forced labor, and a political and economic sovereignty in which citizens depended on global policies and capital flows.

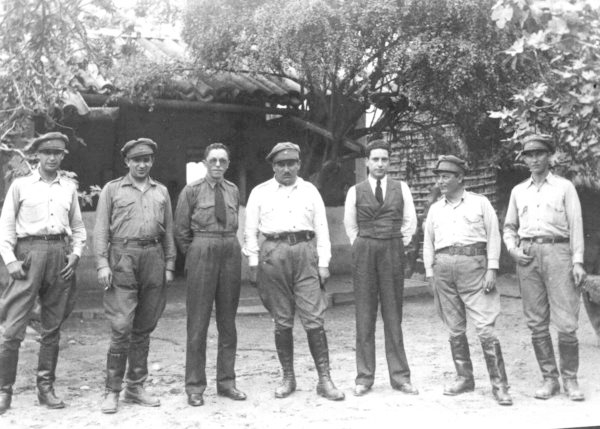

The author begins by showing how the Bolivian-Paraguay War of the 1930s, known in Bolivian history as the Chaco War, was mutually favorable for the Standard Oil Company in Bolivia and for the United States. This event began a history of extraction and commercialization of fossil fuels in the country. At the same time, this war demonstrated how the Bolivian state prioritized the life of certain citizens over others by sending indigenous people from the country’s lowlands to the front lines. In the following chapters, the author explores the nationalization of natural resources under what he calls the “Gaseous State” and the emergence of MAS (Movement Towards Socialism) as a political party under the leadership of Evo Morales, the country’s first indigenous president.

Ballivián, Toro, Peñaranda, and Busch would later become Bolivia’s presidents.

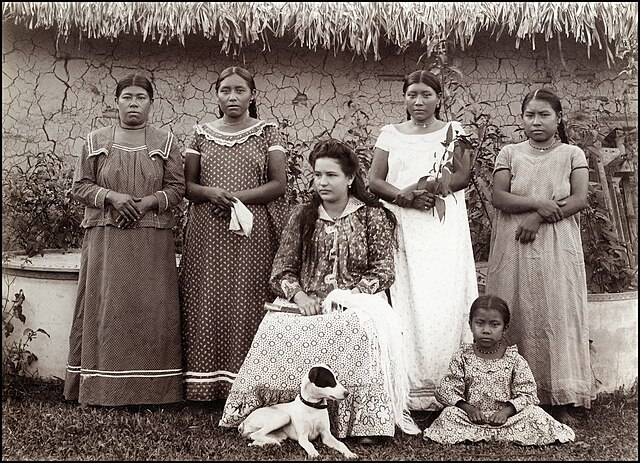

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In his final chapters, Gustafson presents a moment of excess, waste, and the fall of the “Gaseous State.” This book not only presents the development of the “Gaseous State” but also a history of the United States imperialism and the consequences of the relationship between the two countries. The reader can see how gas in Bolivia becomes a transnational geopolitical concept that affects political decisions and reinforces racial tensions. A very important aspect shown in the text is that Evo Morales represented a change in Bolivia, as he was from the highlands and not the lowlands, where most of the deep-rooted questions of exclusion and racism took place. This made him a key strategic figure between middle- and high-class elites, the United States, and indigenous people.

The book sets up an important dialogue between historical and anthropological sources. The text could be considered a historical ethnography that could benefit both fields of research. It combines a deep history of Bolivia’s natural resources with ethnographic fieldwork. It is important to mention that the author has been working with indigenous movements in Bolivia for over thirty years. This book reflects the friendship and commitment he has developed with the Guarani and how he has been able to observe both sides of the story as an author from the United States.

Another element that accompanies the text and allows the reader to engage easily is photography. The images reflect key moments of the book and, at the same time, allow the reader to have a visual journey of the changes in neoliberal politics and commercial development in Bolivia. Also, the author constantly mentions the figure of Evo Morales and his connection with Bolivian racial tensions and gender violence. In terms of gender violence, although the author intends to portray and approach certain moments of Bolivian history with a gender perspective, the depth in which he addresses the topic is shallow and confusing and does not add to the narrative. The way in which gender is portrayed allows the reader to see that Bolivia is a sexist country in which women suffer distinctive violence regarding their sexuality, morals, and daily life practices. Still, the text does not permit the reader to fully grasp the dimensions, the layers, and the complex intersectionality between class, race, and gender and how this affects different women in Bolivia.

Bolivia in the Age of Gas asks readers to be critical and pose questions about political projects, international relations, and racial and social inequality. It is interesting to see how the author produces a narrative through the lens of the natural gas industry. This makes the book an interesting and innovative analysis and permits the reader to pose deep critical questions about social changes through the management of natural resources. Although the book is in English, the author explains a range of concepts in Spanish and provides the reader with a dictionary of key terms and abbreviations used in the book. This could be interpreted both as an academic and a political decision that positions Bolivia in the Age of Gas as a critical and necessary text for academia and an excellent read for someone trying to grasp and understand the history of the current changes happening in Latin America. It allows several disciplines to begin to observe critical problems through lenses like natural resources, contemporary problems in geopolitical dimensions, and the role of the United States in the neoliberal politics of Latin American countries.

Maria Mercedes Gómez was born in Bogota, Colombia. She is an MA fellow student of Latin American Studies at UT Austin. Her work centers around the recognition of victims and minorities in Latin American democracies, with special emphasis on Colombia and Mexico.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

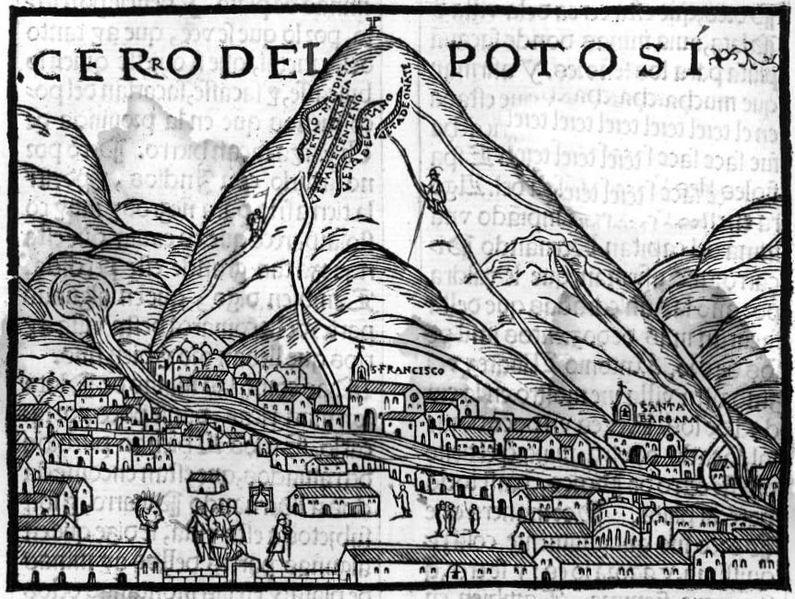

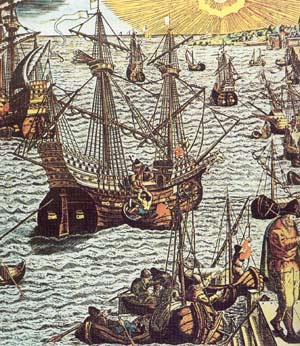

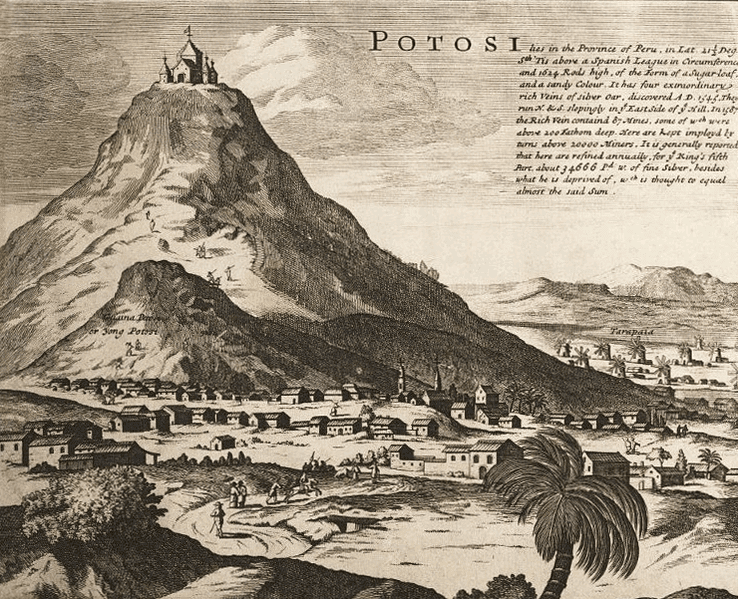

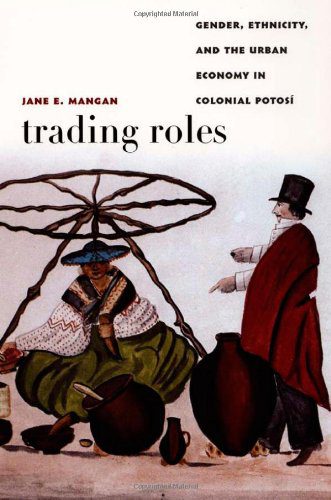

With twice the total population of all of Britain’s North American colonies, Potosí became one of the largest cities in the Americas despite being at an elevation of over 13,000 feet. This expansion centered on the massive silver mines at the nearby Andean mountain of Potosí that fueled Spain’s imperial ambitions. How did the city’s infrastructure keep pace with this startling urban growth?

With twice the total population of all of Britain’s North American colonies, Potosí became one of the largest cities in the Americas despite being at an elevation of over 13,000 feet. This expansion centered on the massive silver mines at the nearby Andean mountain of Potosí that fueled Spain’s imperial ambitions. How did the city’s infrastructure keep pace with this startling urban growth?