In this gendered labor history, Heidi Tinsman looks at the lives of rural agrarian workers under Salvador Allende’s socialist revolutionary government. She examines women’s participation in — and exclusion from — agrarian production and reform in Chile. Tinsman makes a major contribution by showing that the marginalization of women affected the success of Allende’s efforts to expropriate land and create worker-run agrarian cooperatives.

Drawing on a wealth of oral testimonies and legal sources, Tinsman shows how agricultural workers lived under the highly exploitative systems of inquilino and obligado labor in the years before Allende came to power. The author then chronicles the Christian Democratic regime’s initiation of agrarian reform in 1964. The Christian Democrats sought to modernize industry, punish abusive patrons, unionize laborers, and raise the rural standard of living. As a result the number of unionized workers rose from 2,000 in 1964 to a quarter of a million by 1972. The reformists were not revolutionary, however, and although they encouraged workers to resist landowners, the Christian Democrats did not challenge state authority.

After his election in 1970, Allende called for the complete destruction of latifundia. He quickly doubled the amount of expropriated land and converted it into communally run plots, known as asentamientos, which incorporated approximately 20,000 Chilean families. Although still operating hierarchically, asentados (the workers in charge of asentamientos) paid workers more fairly than patróns and made collective decisions about production and construction. Only men were allowed to serve as asentados, however, which excluded wives (who were seen as dependents) and single women who allegedly lacked the requisite experience.

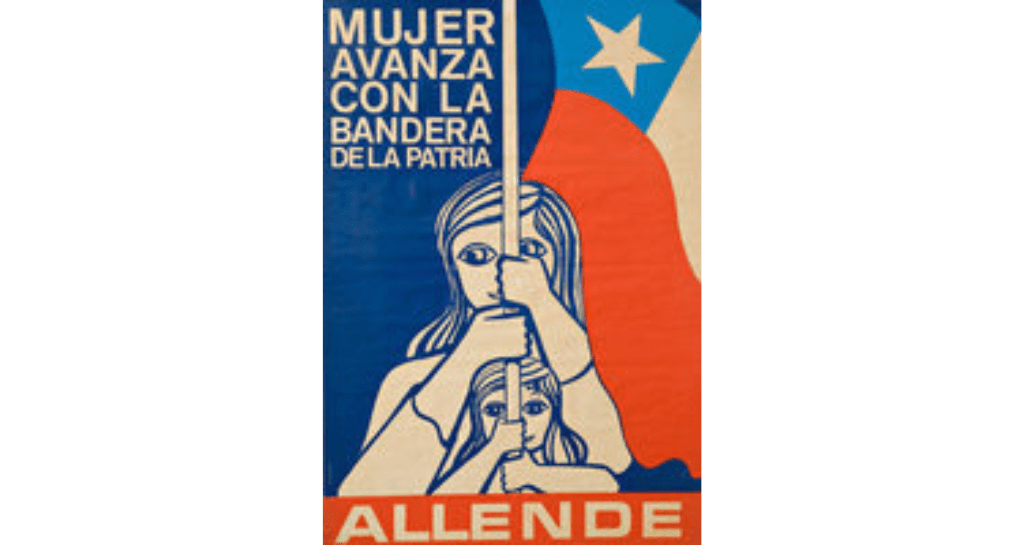

The impact of agrarian reform on women was mixed. For example, the Unidad Popular (Allende’s party, the UP) did not respond to feminist calls to reassess domestic divisions of labor that restricted women’s ability to participate in working communal plots. Nonetheless, women assumed new levels of political activism: they participated in land tomas (takeovers), successfully demanded housing reform, and coordinated community soup kitchens. Women’s Committees (CEMAs) flourished, union membership skyrocketed, infant mortality dropped by 60%, and illiteracy was halved.

Historians traditionally depict rural women as conservative, religious, and opposed to political change. Tinsman shows that in Allende’s Chile this was not the case. Women in Aconcagua, for example, were not particularly religious and rural female support of the UP grew stronger as land expropriation accelerated. To investigate how women experienced the reform, Tinsman explores on-the-ground issues that produced social polarization in rural Chile. Some campesinos, for example, opposed expropriation and defended the bosses, which at times provoked bloodshed. Problems also arose when husbands excluded their wives from politics and took advantage of their political positions in order to take mistresses. To make matters worse, rural food distribution was politicized, and UP supporters often received more rations. Amidst the political and social turmoil, charges of wife beating tripled in comparison to the Christian Democrat years, and rape charges increased as well. Although Tinsman interprets these figures at face value, they are not clear indicators of increases in abuse, because, under the UP, women might have felt more empowered and thus filed more charges.

While Allende’s approach to women and gender was more radical, egalitarian, and feminist than the Christian Democrats who preceded him, Tinsman shows that men were still the “central subjects and main protagonists” of agrarian reform, while women experienced “sexually inscribed vulnerability within the process of political struggle.” Women worried about the effects of social upheaval on their families, which was sadly ironic because “the family continued to be central to female survival and still loudly touted by the UP as the foundation of social uplift.”

Heidi Tinsman, Partners in Conflict: The Politics of Gender, Sexuality, and Labor in the Chilean Agrarian Reform, 1950-1973

You may also like:

Elizabeth O’Brien’s review of Gendered Compromises: Political Culture and the State in Chile, 1920-1950 by Karin Alejandra Rosemblatt

Monica Jimenez, Remembering Pinochet’s Chile by Stephen Stern

Image of Women Advance with the Flag of the Motherland” poster courtesy of Centro de Documentación Salvador Allende

![An image from "Flora Huayaquilensis," a visual collection of South America's plants as seen by Spanish botanist Juan José Tafalla during a 1785 expedition through Peru and Chile. ([Juan Tafalla], “Flora Huayaquilensis,” ourheritage.ac.nz | OUR Heritage - See more at: http://otago.ourheritage.ac.nz/items/show/7696#sthash.r8R9WHhx.dpuf)](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/87bbce75b1706f7ba39ef9bcbb7c9560.jpg)