At the beginning of 1941, Sergei Eisenstein was feeling defeated. Three years had passed since he had completed a film and, on January 2, the great Russian film maker confided to his diary that he felt like his broken-down car, lethargic and depressed. A few days earlier, tired of waiting for the film administration to approve his latest proposal, he had written directly to Joseph Stalin, requesting him to intercede. When the phone rang on January 11, it was Andrei Zhdanov, secretary of the Central Committee and member of the Politburo’s Committee on Cinema Affairs, calling to say that no one was interested in his most recent pitch, but that they should meet to discuss the film Stalin wanted him to make. We don’t know exactly what was said at that meeting, but immediately afterward Eisenstein began reading and thinking and jotting down ideas about Ivan the Terrible, the tsar who ruled Russia in the sixteenth century. By January 21, the possibilities for a film on Ivan had captured his imagination and would not let him go. Eventually, he would fill more than a hundred notebooks with ideas related to the film and finish two books of film theory and one 800-page memoir deeply imprinted by his experience of making it. He was writing about Ivan the Terrible when he died, at age fifty, only seven years later.

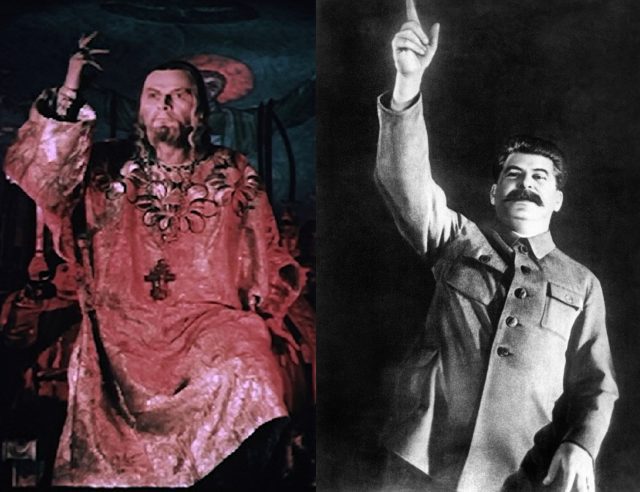

In commissioning a film about Ivan the Terrible, Stalin expected Eisenstein to celebrate Ivan as the first tsar, a progressive and visionary leader, and the founder of a unified, centralized, modern Russian state. What made it tricky is that Ivan the Terrible, like Stalin himself, was infamous for carrying out a ruthless campaign of terror against the people he ruled. Everyone expected Eisenstein to make a film that justified Ivan’s violence as necessary for defeating those who opposed him in founding and protecting the new state. Stalin, who didn’t like surprises, got much more than he bargained for. Eisenstein’s film ranged far from the official commission and was controversial even before it hit the screen. Ivan the Terrible was not only a shrewd critique of Stalin and Stalinism, it also raised profound questions about the nature of power, violence, and tyranny in contemporary politics, and in the history of state power more broadly. Eisenstein’s film used Ivan’s story to examine the psychology of political ambition, the history of absolute power and recurrent cycles of violence. It explores the inner struggles of the people who achieved power as well as their rivals and victims.

Eisenstein worked on Ivan the Terrible for five years, from January 1941 to February 1946, completing only two-thirds of a projected three-part film. Part I of the trilogy was completed in December 1944 and went into general release in early 1945; Part II was submitted in February 1946; it was banned in March and only released in 1958; Part III remained incomplete at Eisenstein’s death in February 1948, but the screenplay, some footage, and many of his notes have survived.

Ivan the Terrible took so long to make because production was repeatedly postponed by the second World War. A few months after receiving the commission, on June 22, 1941, Eisenstein’s work on the screenplay was interrupted when the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union. As Artistic Director of the Moscow Film Studio (Mosfilm), he was immediately put in charge of producing morale-lifting films and dealing with supply, personnel, and production problems brought on by the war and the nightly bombing raids that began in July. As German troops moved close enough to threaten Moscow, most of the population of the capital, including its entire film industry, was evacuated to Alma Ata (Almaty) in Kazakhstan. It took another year for negotiations over the screenplay and the casting to conclude, and filming itself didn’t begin until April 1943.

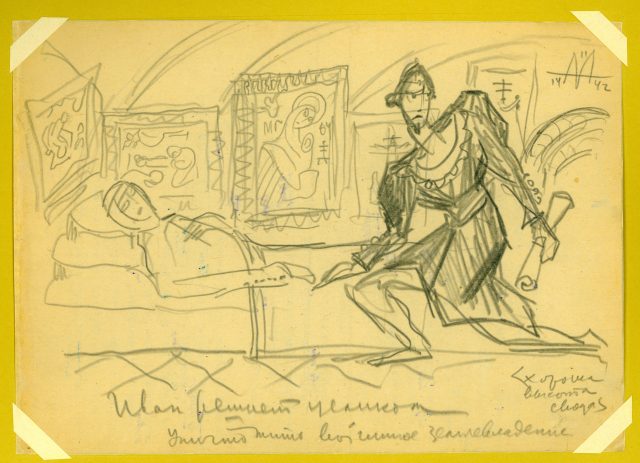

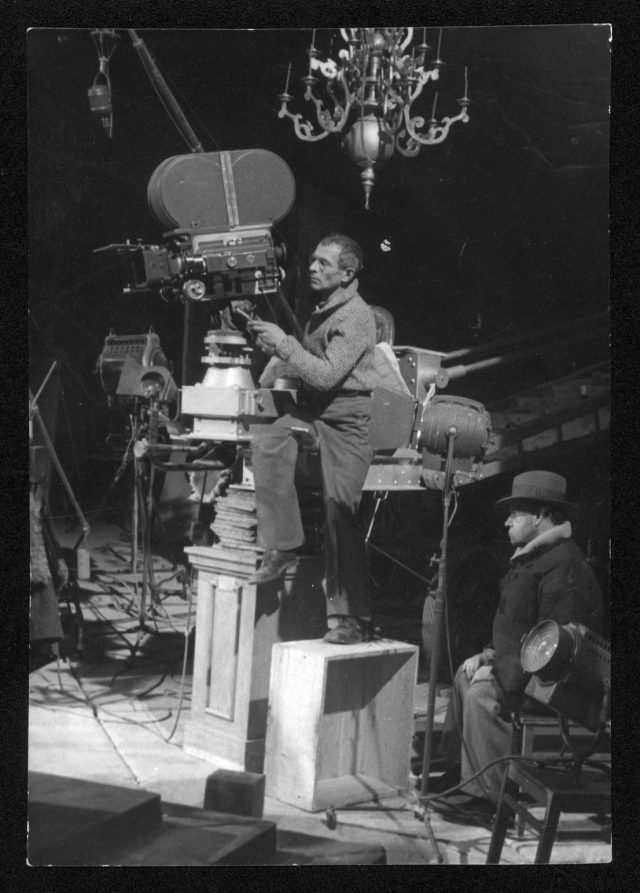

During the long months of waiting, Eisenstein read hundreds of books, filled dozens of notebooks with ideas, and made thousands of drawings. In addition to the story-boards, he drew his memories of other times and places, illustrations of the books he was reading, caricatures of his colleagues and friends, and sexually explicit fantasies and satires. Despite the often inhuman forms represented in his story boards, Eisenstein insisted that his actors reproduce the poses he envisioned and hold those poses for hours at a time. He was famous for his ability to use pranks and jokes to defuse tension on the set, but not all the actors loved the demanding physical workout Eisenstein required.

Once underway, Eisenstein took his time, as meticulous as he wanted to be and determined to make the film he wanted to make. He worked closely with his brilliant cameraman, Andrei Moskvin, his lead actor, Nikolai Cherkasov, and the renowned composer, Sergei Prokofiev, who wrote the score, all of whom shared his willingness to risk making the transgressive film Eisenstein had in mind.

For many viewers, the result was alienating and difficult to understand. American critic Pauline Kael famously wrote that Ivan the Terrible was “so lacking in human dimensions that you may stare at it in a kind of outrage. True, every frame in it looks great – it’s a brilliant collection of stills – but as a movie, it’s static, grandiose, and frequently ludicrous.” That’s not really what Eisenstein was going for. The Russian critic Sergei Yutkevich came closer; he saw Ivan as “a symphonic film [that] puts all his tremendous culture of cinematographic expression into the service of his theme and, as in no other film of his, he achieves a unity of the different expressive means available to the cinematic art. This is not only a brilliant duel of remarks and glances but a passionate battle of sound and silence, light and dark. Brightness and shadow, color and textures—all influence one’s mind and feelings.”

The strange look and feel, and the difficult narrative were intentional. Not only did Eisenstein have to evade the censor and the wrath of the ruler, but the complexities of Ivan’s biography paralleled his ideas about cinematic method, about how to make a film that would have the greatest emotional and intellectual impact. Eisenstein was the first film theorist to systematically explore the ways films are constructed and the ways viewers perceive what they see on screen. He was also one of the first modern thinkers to explore the ways feeling were as important as thinking in both the production and reception of art. Studying biography and history for the first time when making Ivan the Terrible also convinced him that feelings were as important as ideas in shaping the decisions that historical and political figures make.

To tell the story of Ivan the Terrible, Eisenstein wanted not just show but make us feel Ivan’s hunger for power and the ensuing conflicts that resulted. To draw viewers in and engage our deepest feelings and most complex thinking, Eisenstein devised two parallel strategies. First he believed that viewers respond consciously and unconsciously to even the tiniest of details that we see and hear when watching a film. So he broke down every element of the film image to its constitutive parts, what he called its “essential bone structure,” for the audience to gradually reconstruct for themselves into something meaningful and moving. This is why Eisenstein had his actors hold such inhuman poses: so that viewers would see every single minute gesture that went into conventional movements. This is why the production design exaggerated and distorted familiar images – from religious icons and rituals, for example. And this is why we see a hodge-podge of visual styles juxtaposed — melodrama, tragedy, gothic, grotesque, satire, and comedy. All of these design choices were meant not just to challenge conventional meanings but to let the viewer see from Ivan’s point of view, by compelling us to engage in the same process of making sense of fragmented, contradictory cues.

At the same time, Eisenstein structured the narrative around a set of questions. How does an innocent, vulnerable child become a sadistic, bloody tyrant? To what extent is Ivan like the people around him and, by extension, like us? When is killing justifiable? Do Russian rulers and, by implication, all Russians differ from their contemporaries in the West? When are we responsible for our own actions, and when can we blame circumstances? Each scene raises these questions in some form, so the audience is constantly being invited to wonder, compare, evaluate, and judge. And underlying these moral-political issues is a set of related questions concerning human emotions. In general, Ivan the Terrible asks us to consider what role emotions play—in relation to reason and logic—in motivating us to act. More specifically, Eisenstein asks what happens when love, affection, sexual attraction, grief, loneliness, hate, distrust, and the desire for revenge enter into politics. How are political affections and rivalries gendered? What happens when we are asked to love a ruler like a father? What role does affection play in a political brotherhood?

These are not the typical structuring devices of the Stalinist biopic. Soviet film biographies of this period were supposed to provide clear-cut models of behavior. Individuals in film biographies, whether cult figures or ordinary people, were to undergo some transitional improvement, make a heroic contribution to their community, and offer moments of inspiration and motivation. Eisenstein’s interrogative mode challenged viewers to make up their own minds. The ambiguities of the interrogative deny viewers a neutral vantage point and challenge us to reclaim our authority to make meaning from observation and experience.

Part I of Ivan the Terrible gives us a young and determined ruler, committed to defeating Russia’s external enemies, and the obsolete aristocracy, who opposed his efforts to centralize Russian power and establish The Great Russian State. And apparently the portrait of Ivan was just monumental and triumphalist enough for Part I to win the Stalin Prize and cause American critics to see it as pure Soviet propaganda. But this view of the film required ignoring the paranoia, violence, trauma, vengeance, treason, and betrayal that permeate its story, its characterizations, and its bizarre and murky visual setting. Ivan himself is beset by inner conflicts over his mission and constantly asks if he is on the right path. He repeatedly beseeches himself, his friends and his enemies, God, and the audience, “Am I right in what I am doing?” His own uncertainty cues us to ask if the opposition to the centralization of power is, perhaps, in some ways justified, a question that is, in fact, at the heart of Eisenstein’s conception of the film. In Part II, the questions become darker, revolving insistently around cycles of murder and revenge. Ivan still asks for reassurance but God is silent and no one else gives him the answers he wants, spurring him on to greater, more vicious acts of violence.

Ivan declaring that he is free to act against the country’s enemies (L) Stalin in a widely reproduced photograph by Ivan Shagin (R)

All Eisenstein’s questions had obvious analogues in Stalinist society. But the film maker was after something more than simple critique. He wanted to explain how Ivan became the bloody, manipulative, demagogic tyrant he became. Eisenstein had stated from the beginning that he did not intend to “whitewash” the medieval ruler or justify his violent reign, but rather to explain, as he put it, “the most atrocious things.” The interrogative mode that he used in Ivan the Terrible established a set of standards for judging any ruler. That’s how you make a film about a bloody tyrant for a bloody tyrant.

If Stalin was instrumental in bestowing Part I with the Stalin Prize, he hated Part II and had it immediately banned.

Ivan the Terrible is a difficult film because it continually presents us with contradictions and questions, it forces us to respond to unfamiliar, difficult, and ambiguous cues, and it denies us a hero to identify with or a villain to hate. It is a great film because it creates a portrait of power that resists simplification and provokes us to engage with hard questions, precisely the hard questions the Stalinist artist was supposed to suppress.

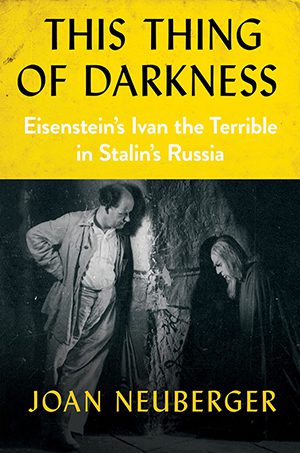

This Thing of Darkness: Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible in Stalin’s Russia

Cornell University Press, 2019

For more on Eisenstein and early Soviet filmmaking, you might like these:

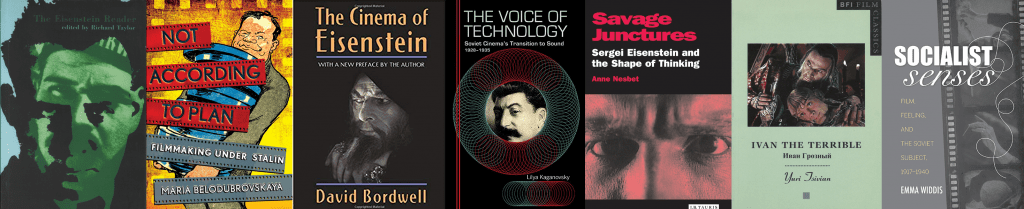

The Eisenstein Reader, edited by Richard Taylor, translated by Richard Taylor and William Powell (1998)

A good selection of Eisenstein’s writing, translated into English.

Maria Belodubrovskaya, Not According to Plan: Filmmaking Under Stalin (2017)

A history of Soviet filmmaking that focuses on film institutions rather than political leadership.

David Bordwell, The Cinema of Eisenstein (2nd edition, 2005)

A comprehensive and insightful survey of Eisenstein’s films by one of the leading film historians in the US.

Lilya Kaganovsky, The Voice of Technology: Soviet Cinema’s Transition to Sound (2018)

Analyzes the unique ways sound shaped cinema in the the Soviet Union. Kaganovsky shows that sound films made the voice of state power audible, reaching viewers directly for the first time.

Anne Nesbet, Savage Junctures: Sergei Eisenstein and the Shape of Thinking (2003)

A study of each of Eisenstein’s films in the context of the director’s unpublished writing, that shows the importance of contradiction, fracture, and wildly imaginative and beguiling strangeness in all his work.

Yuri Tsivian, Ivan the Terrible (2001)

An intertextual study of Ivan the Terrible that provides sharp insights into Eisenstein’s thinking in images.

Emma Widdis, Socialist Senses: Film, Feeling, and the Soviet Subject, 1917-1940 (2018)

With a focus on the depiction of the senses in an extraordinary range of early Soviet films, this book shows how the new Soviet subjectivity was shaped first by a revitalized engagement with the material and natural world and later by an enriched inner emotional world.