From the editors: Notes from the Field is a series with a long history at NEP. In this latest iteration, the series has three broad areas of focus. First, Notes from the Field is designed to take readers into unexpected corners of the world’s great archives and to explore the experience of working there. We aim to describe some of the spaces and places in which historians work every day. Second, we’re interested in fascinating stories that might not become the central focus of a book or an article but which nonetheless reveal intriguing corners of the past. And third the series discusses the often unexpected experiences of doing fieldwork where each day can bring new challenges, joys or discoveries. Together these stories form our new Notes from the Field.

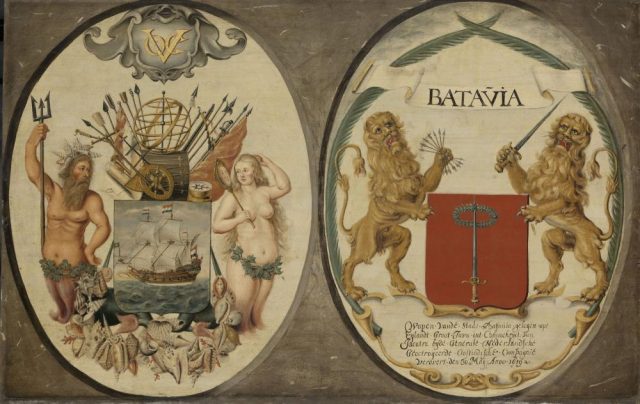

I’m a historian of early modern East and Southeast Asia, so I’m fortunate to work in some of the most interesting archives in the world. I spend a lot of time at the National Archives in The Hague, a city in the Netherlands with a long history. This archive stores hundreds of thousands of documents connected with the Dutch East India Company (the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, or VOC), which carved out a commercial empire in Asia in the seventeenth century.

I’ve used archives across four continents. The National Archives is undoubtedly the most accessible and user-friendly archives I’ve ever worked in. You can travel there by train, registration is simple, and it’s easy to get access to original documents rather than poor microfilmed copies. It’s a wonderful place to work.

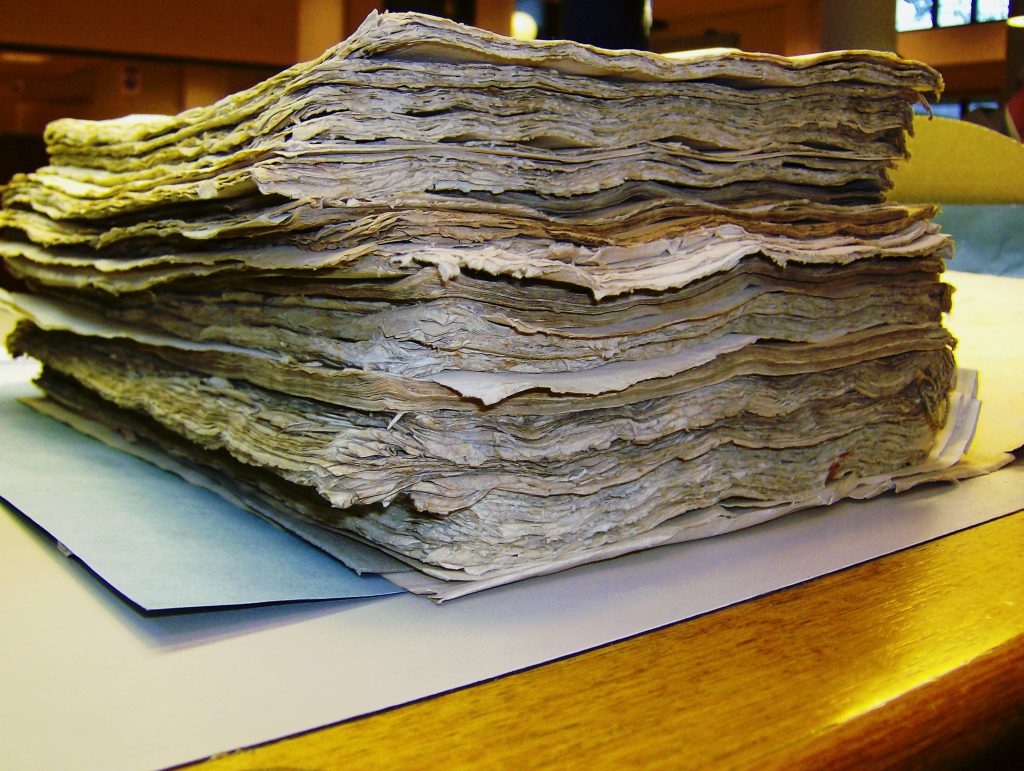

But it can also be a little overwhelming. Within an hour after arriving, you can find yourself confronting huge piles of documents, invariably written in the dense and idiosyncratic script of VOC employees. That script, especially as used in earlier documents, can takes dozens of hours per source to decipher.

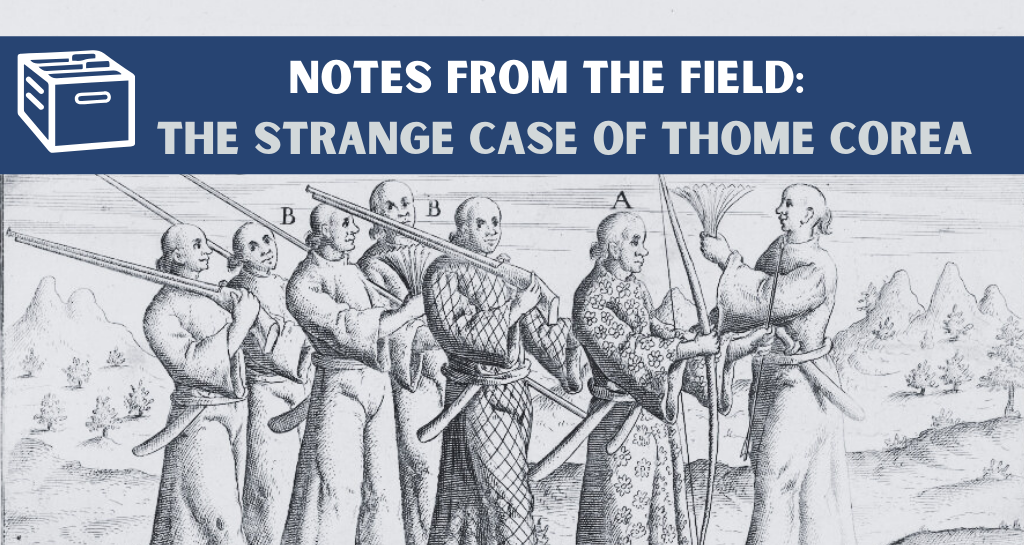

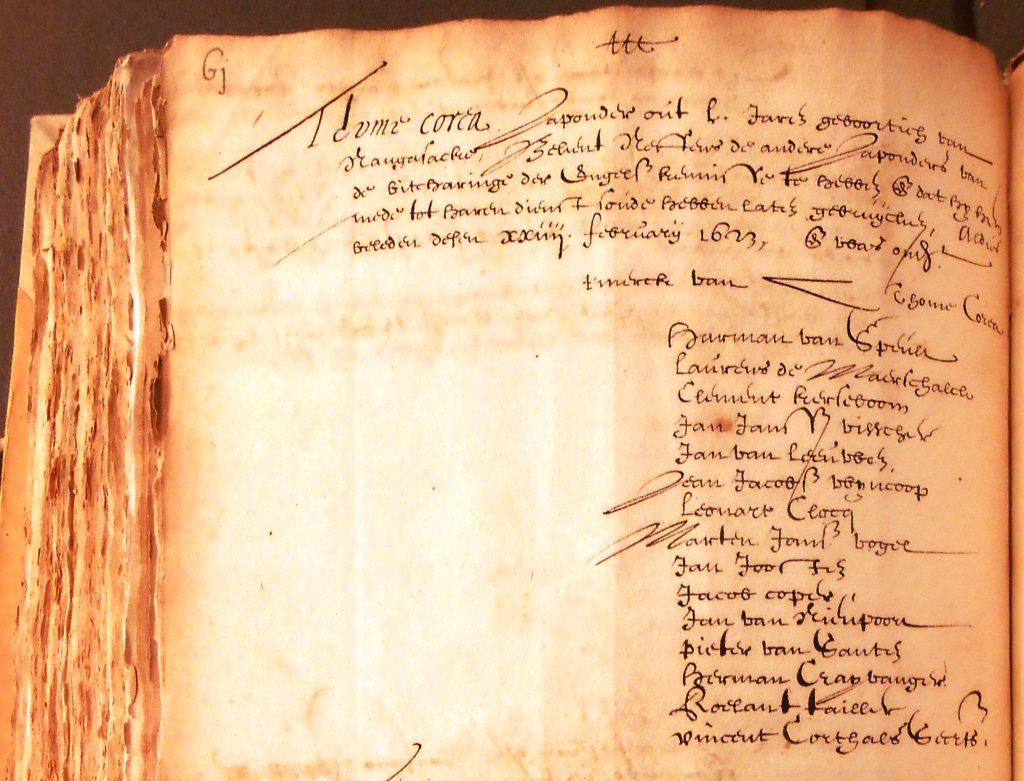

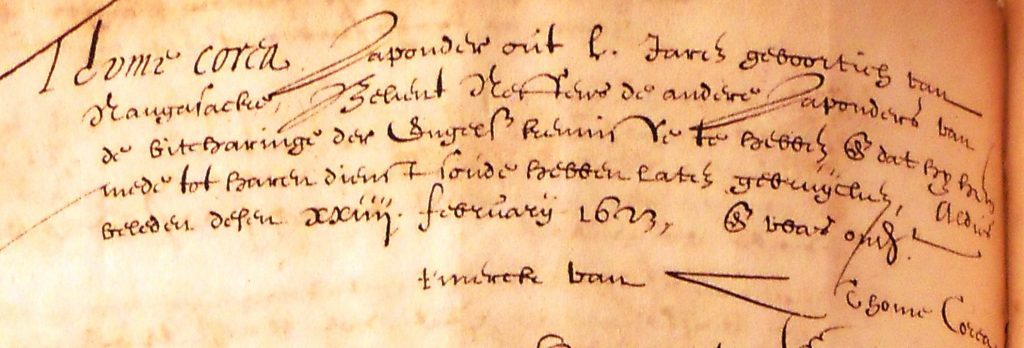

The challenges involved in doing research at the National Archives are daunting, but this also makes working there exceptionally exciting, as historians frequently come across documents that no one has seen in hundreds of years. One of my favorite documents is just one page long. It’s a confession signed by Thome Corea, a ‘Japanese’ mercenary who was stationed on a remote island in Southeast Asia in 1623.

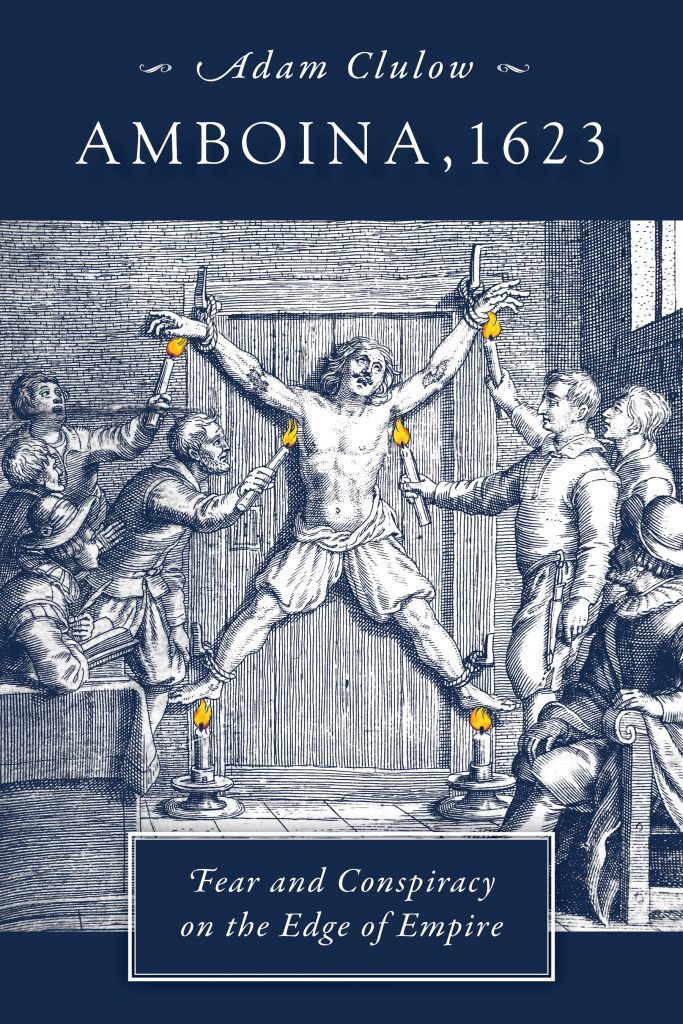

The document is connected with the Amboina conspiracy case, the subject of my recent book. The case started with one of Thome Corea’s fellow soldiers. On February 23rd, 1623, a Japanese mercenary called Shichizō, in the employ of the Dutch East India Company, was arrested for asking questions about the defenses of one of the company’s forts on the remote island of Amboina in modern-day Indonesia.

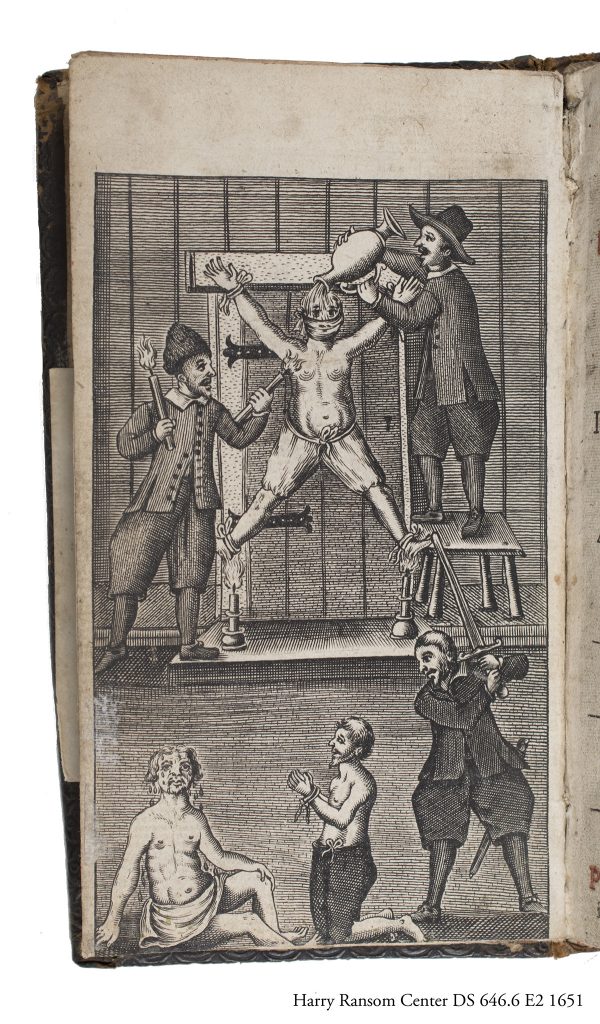

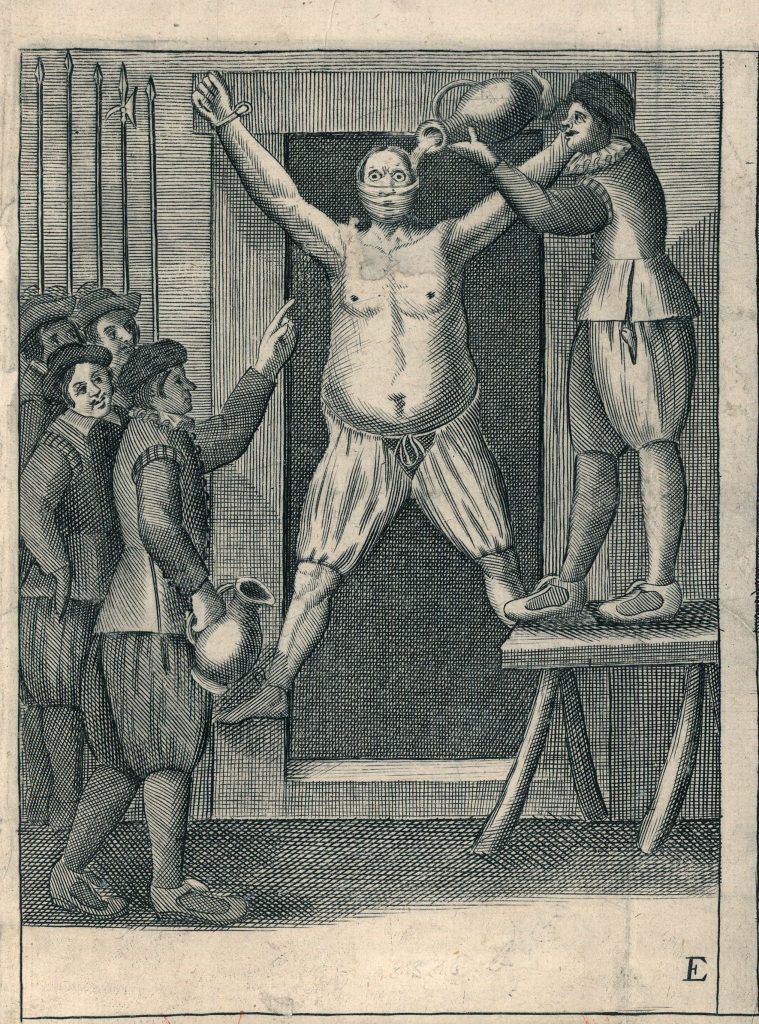

When he failed to provide an adequate explanation, he was subjected to the “torture of water”: a cloth was “put before his face and fastened behind his head, hanging upon under his chinne, [and] after this the water was poured upon his head.” The result of this process, which we would call waterboarding today, was a confession claiming that Shichizō had joined a plot orchestrated by a group of English merchants. The merchants allegedly hoped to seize control of the VOC fortification and ultimately to rip the spice-rich island from the company’s grasp.

Armed with this information, the VOC governor proceeded to arrest, interrogate, and torture the remaining ten Japanese mercenaries in the garrison, all of whom (including Thome Corea) admitted to signing onto the plot in return for a substantial reward. A few days later, attention turned to the English, who also confessed–again, under torture–to a role in a conspiracy aimed at the “taking of the castle, and the murdering of the Netherlanders.” On March 9th, an improvised tribunal of VOC employees with the governor at its head convened to render judgment on the conspirators. The result was an emphatic guilty verdict, and shortly thereafter, ten English merchants and ten Japanese mercenaries were executed in the public square outside the fortress.

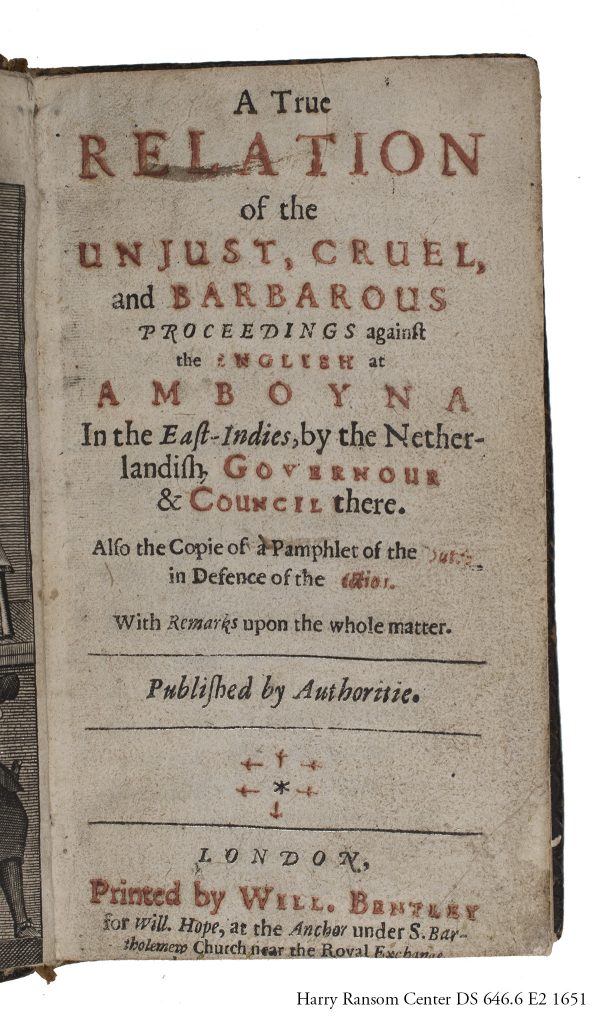

The case became enormously controversial in Europe. When news of what had happened reached London in 1624, it sparked an immediate outage. English officials denounced the flawed nature of the judicial procedures while ridiculing the notion that a conspiracy had existed in the first place. As news of the trial spread, propelled by the publication of cheap broadsheet ballads and incendiary pamphlets, everyone seemed to be talking about Japanese soldiers and their particular capabilities.

For Dutch writers determined to emphasize the potential strength of the Amboina plotters, the Japanese were fearsome warriors capable of swaying the outcome of any conflict. A “small number of Japonians were not slightly to be regarded,” exclaimed one writer, as the “valour & prowess of that Nation” made them far more potent than an equivalent contingent of European soldiers. Not so, scoffed their English opponents, who claimed that the Japanese were no military “Gyants” and that the wondrous feats ascribed to them nothing more than “Apochriphal Legends” with no basis in fact.

One of the ‘Japanese; soldiers caught up in the Amboina case was Thome Corea. He was tortured and waterboarded by Dutch officials and rapidly confessed. But as he was illiterate, he could not sign his name. Instead, he made a rough mark.

Although he represented himself as a ferocious Japanese soldier, Thome Corea was not actually Japanese. In fact he was Korean. And he had a remarkable life. We know from the records associated with the trial that Corea was aged fifty in 1623, meaning that he was born around 1573. He was thus likely brought to Japan in the turbulent aftermath of Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s massive invasion of Korea in 1592.

He probably came to Japan as a young captive along with tens of thousands of Korean children, women and men who were enslaved by the returning armies. Keinen, a Buddhist monk who traveled to Korea as part of the invading forces, observed the mass transport of children: “They are carrying off Korean children and killing their parents. Never shall they see each other again. Their mutual cries—surely this is like the torture meted out by the fiends of hell.” (1) Thome Corea may have been one of these children.

At some point, he secured his freedom but was unable to return to Korea. Instead, like so many of his countrymen he was drawn to western Japan’s bustling cosmopolitan ports like Nagasaki or Hirado. There he seems to have eked out a living until the Dutch East India Company came recruiting. It offered three year contracts, dangerous work, and poor conditions–but also the promise of a steady wage.

Corea’s unlikely career suggests that the Company’s attempts to recruit legion of Japanese soldiers to fight on its behalf opened up an unexpected space for reinvention, one in which a Korean captives could morph, in search of a stable wage, into a fearsome Japanese soldier. If so, Corea was not alone in making this change. VOC records include multiple references to “Japanese” soldiers with names that suggest links to places like Macao, China or Korea but who were able to take advantage of new opportunities afforded by the Company’s martial visions.

Thome Corea generated just a few lines in the sources and one hastily scrawled cross to mark his confession. He was part of important events in global history but he did not drive them. But his story is important. Like so many historians, I love working in the archives because I’m able to uncover evidence of hidden lives. Thome Corea is an example of such a life.

(1) Wm. Theodore de Bary, Donald Keene, George Tanabe, and Paul Varley, ed. Sources of Japanese Tradition : Volume 1: From Earliest Times to 1600 (Columbia University Press, New York, 2010: 467-72

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.