A swarm of plump and colorful waxwings are feasting on rowanberries. Suddenly, a shot rings out. “A good dozen of the birds tumble from the fruit clusters down into the snow amidst fallen berries and drops of blood. Who can tell whether the survivors will ever return?” With this scene Gregor von Rezzori begins his memoir of a boyhood in Czernowitz, a city that in the course of the twentieth century was variously located in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Romania, the Soviet Union, and today’s Ukraine. A sense of irretrievable loss and dislocation, amid images of beauty and destruction, are central themes in this intimate story of the disappearance of Habsburg Europe.

Born on the eve of the First World War, Gregor von Rezzori grew up in a family that, much like his hometown, was profoundly shaken by the collapse of Austria-Hungary. Czernowitz, the capital of the region known as Bukovina, was one of the empire’s most eastern outposts. Nevertheless, it was known as “Little Vienna” due to its vibrant cultural life and architecture. This was a city shared by Jews, Orthodox Christians, and Catholics, in which a multiplicity of languages could be heard. A place that, through the eyes of young Gregor, was deeply connected both to the land around it and to the imperial capital Vienna.

Von Rezzori’s parents belonged to the city’s German-speaking elite. His father was an Austrian public servant in charge of inspecting the province’s Orthodox monasteries, a position he used ostensibly to indulge his passion for hunting on the large estates owned by the Church. An inattentive husband living well beyond his means and with little patience for domestic traditions and social norms, he saw his fatherly duties as limited to raising his son as a huntsman. His high spirits and love of life stood in stark contrast to his wife’s demeanor. Von Rezzori’s mother, frustrated by a life that didn’t conform to her sense of stature nor her expectations of domestic bliss, escaped their home in Czernowitz to spas and health resorts as far away as Egypt. If weak health had been a pretext for her earlier absences, as a mother of two, she became obsessed with illnesses, smothering her children, Gregor and his older sister Lisa, with overprotection and anxiety. In von Rezzori’s world, parents set expectations. The nurturing, however, was done by others: his peasant nurse Cassandra, known in the household as “the savage one,” and later by Bunchy, his worldly and cheerful governess.

Von Rezzori’s parents belonged to the city’s German-speaking elite. His father was an Austrian public servant in charge of inspecting the province’s Orthodox monasteries, a position he used ostensibly to indulge his passion for hunting on the large estates owned by the Church. An inattentive husband living well beyond his means and with little patience for domestic traditions and social norms, he saw his fatherly duties as limited to raising his son as a huntsman. His high spirits and love of life stood in stark contrast to his wife’s demeanor. Von Rezzori’s mother, frustrated by a life that didn’t conform to her sense of stature nor her expectations of domestic bliss, escaped their home in Czernowitz to spas and health resorts as far away as Egypt. If weak health had been a pretext for her earlier absences, as a mother of two, she became obsessed with illnesses, smothering her children, Gregor and his older sister Lisa, with overprotection and anxiety. In von Rezzori’s world, parents set expectations. The nurturing, however, was done by others: his peasant nurse Cassandra, known in the household as “the savage one,” and later by Bunchy, his worldly and cheerful governess.

The memoir is deeply personal, organized around stories of family members rather than chronology. Its locus is Czernowitz in the years following the First World War when the old order has collapsed. Although its inhabitants were now Romanian subjects, life in some ways went on as it had before. However, the gradual crumbling of the world of Austria-Hungary manifested itself in the anxieties that filled his boyhood home. His parents—reduced from social, cultural and political elites to relics of the old order—divorce, thereby adding new layers of uncertainty. Gregor’s mother, for example, seeks to uphold her family’s elite stature even as its social foundations disappear. She does so by quarantining her son in the house and garden, thereby protecting him from the contamination that was sure to result from play with other children or from venturing out into the world beyond the yard fence. His father, whose pension vanishes with the Austrian state, retreats to live and hunt among Transylvanian Saxons, a German-speaking minority in Romania’s north.

Although infused with a sense of dislocation, von Rezzori’s recollections are at the same time intensely rooted in the city’s streets and squares, its sounds and smells, in the landscapes that surrounded it, and in its rich mixture of peoples and cultures.

Gregor von Rezzori eventually left Romania for Austria, Germany, the United States, and Italy. He wrote many works of fiction drawing on his own experiences. He died in 1998. The Snows of Yesteryear is a deeply moving reflection on belonging and displacement and offers a glimpse into a multicultural world that was eventually obliterated in the calamitous Second World War.

Related Reading:

Gregor von Rezzori, Memoirs of an Anti-Semite: A Novel in Five Stories (2007)

Gregor von Rezzori, An Ermine in Czernopol (2011)

Tatjana Lichtenstein elsewhere on Not Even Past: The Shop on Main Street

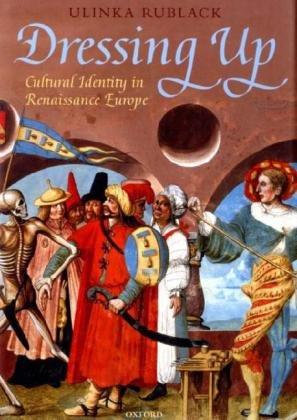

Schwarz’s life may well have been forgotten if he had not taken the unusual step of memorializing it in an extraordinary manuscript. In his Klaidungsbüchlein, or “Book of Clothes,” Schwarz commissioned one hundred and thirty seven vivid watercolor paintings depicting the clothes he wore at each stage of his life, from his “first dress in the world” as a days-old infant to the somber robes of mourning he wore as a world-weary man of sixty-seven.

Schwarz’s life may well have been forgotten if he had not taken the unusual step of memorializing it in an extraordinary manuscript. In his Klaidungsbüchlein, or “Book of Clothes,” Schwarz commissioned one hundred and thirty seven vivid watercolor paintings depicting the clothes he wore at each stage of his life, from his “first dress in the world” as a days-old infant to the somber robes of mourning he wore as a world-weary man of sixty-seven.

by

by

His churchwarden’s accounts are laden with personal commentary, providing a unique window into the lives of ordinary men and women during the years of the English Reformation, when the Church of England first broke away from the Catholic Church in Rome. Though titled the Voices of Morebath, the voice of Sir Christopher Trychay, with all his opinions and biases, dominates the work; The Voices of Morebath is ultimately his story.

His churchwarden’s accounts are laden with personal commentary, providing a unique window into the lives of ordinary men and women during the years of the English Reformation, when the Church of England first broke away from the Catholic Church in Rome. Though titled the Voices of Morebath, the voice of Sir Christopher Trychay, with all his opinions and biases, dominates the work; The Voices of Morebath is ultimately his story.

Eco’s book is deeper and intellectually richer than Dan Brown’s subsequent variations on the same theme, but it is also every bit as thrilling. It takes readers on a journey through time as well as across beautifully detailed spaces from Italy and France to Brazil.

Eco’s book is deeper and intellectually richer than Dan Brown’s subsequent variations on the same theme, but it is also every bit as thrilling. It takes readers on a journey through time as well as across beautifully detailed spaces from Italy and France to Brazil.