By Clay Katsky

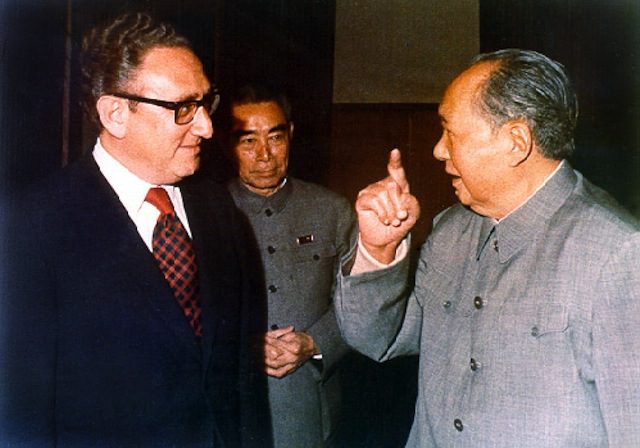

Tickets to “An Evening with the Honorable Henry Kissinger” at the LBJ Library’s Vietnam War Summit sold out in less than one minute. The attention that Kissinger continues to command in 2016 could be linked to the premise of Greg Grandin’s new book. Grandin, a history professor at NYU, portrays the former National Security Advisor and Secretary of State as extraordinarily influential on U.S. foreign policy before, during, and after leaving office. But from the author’s unambiguously leftist point of view, Kissinger’s legacy is anything but honorable. While Grandin cites his most positive achievements, opening China and stabilizing relations with the Soviet Union, the book’s main contention is that Kissinger’s worldview and access to power led him to create a new imperial presidency “based on even more spectacular displays of violence, more intense secrecy, and an increasing use of war and militarism to leverage domestic dissent and polarization for political advantage.” Kissinger brought the old national security state into the post-Vietnam War era.

Tickets to “An Evening with the Honorable Henry Kissinger” at the LBJ Library’s Vietnam War Summit sold out in less than one minute. The attention that Kissinger continues to command in 2016 could be linked to the premise of Greg Grandin’s new book. Grandin, a history professor at NYU, portrays the former National Security Advisor and Secretary of State as extraordinarily influential on U.S. foreign policy before, during, and after leaving office. But from the author’s unambiguously leftist point of view, Kissinger’s legacy is anything but honorable. While Grandin cites his most positive achievements, opening China and stabilizing relations with the Soviet Union, the book’s main contention is that Kissinger’s worldview and access to power led him to create a new imperial presidency “based on even more spectacular displays of violence, more intense secrecy, and an increasing use of war and militarism to leverage domestic dissent and polarization for political advantage.” Kissinger brought the old national security state into the post-Vietnam War era.

Kissinger relaxes at the LBJ Presidential Library before his public appearance on Tuesday, April 26, 2016 at The Vietnam War Summit. Courtesy of the LBJ Library : photo by David Hume Kennerly.

Starting with Kissinger’s legendarily long Harvard undergraduate thesis, Grandin seeks to uncover the ideas, insights, and assumptions that influenced his theories on diplomacy and drove his desire to fashion a new world order based on a balance of power. In focusing on Kissinger’s own writings, the book combines intellectual and diplomatic history. And it offers something new by examining Kissinger’s unique mixture of realism and idealism, which Grandin labels a kind of “imperial existentialism” in which conjecture is more preferable for action than fact because hard facts can be polarizing. Most historians have labeled Kissinger an arch-realist, yet Grandin insists that his more philosophical writings stressed the importance of conjecture in decision-making. In tribute to Kennedy’s handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Kissinger exalted decisiveness above all else: “In reaching a decision, he must inevitably act on the basis of an intuition that is inherently unproveable. If he insists on certainty he runs the danger of becoming prisoner to events.” But Grandin’s link to Cheney’s 1% Doctrine, which he describes as the United States taking action as if mere threats are forgone conclusions, seems tentative and is based on little evidence. Kissinger had hoped that showing strength in Cuba would lead to bolder foreign polices and legitimize American power, but in office his agenda shifted to preventing a decline in American prestige stemming from the pull out of Vietnam.

Kissinger being sworn in as Secretary of State by Chief Justice Warren Burger, September 22, 1973. Kissinger’s mother, Paula, holds the Bible upon which he was sworn in while President Nixon looks on. Via Wikipedia.

According to Grandin, power and prestige were crucial elements in Kissinger’s perception of American security interests. Consciousness of power comes from a willingness to act, and he believed the best way to produce willingness was to act. But nuclear weapons complicated Cold War power dynamics because leaders were afraid to use them. Taking stock of Kissinger’s early academic career at Harvard, Grandin points out that in 1956 he wrote that the more powerful the weapons “the greater becomes the reluctance to user them.” Strength turned to weakness. But Grandin’s emphasis on the future statesman’s earliest writings freezes his worldviews in the 1950s. This in spite of the fact that Kissinger’s early musings on limited nuclear warfare later evolved into his belief that action in small wars in marginal areas could produce enough awareness of power to break the impasse of nuclear power. In this regard, Kissinger saw Southeast Asia as more of an opportunity than a burden. But Grandin doubts his escalation in Vietnam was based on any geostrategic reasoning. Like détente it served a more domestic purpose and, therefore, he brands the extensive bombing of Cambodia as both Kissinger’s most heinous crime and his most enduring contribution to U.S. foreign policy.

In terms of its legality, the bombing set an important precedent for U.S. warfare because it targeted a neutral country. Kissinger justified violating Cambodian sovereignty by citing the need to destroy Communist “sanctuaries” along its border with Vietnam. Grandin links such logic to more recent attacks on terrorist “safe havens,” from George W. Bush’s invasion of Afghanistan in 2002 to Barack Obama’s extensive use of drone attacks in Pakistan and Syria. Although Kissinger fell out of favor with the conservative establishment when Reagan began hammering him on détente, this connection is based on good evidence. Desperate to distance itself from talk of power balances and American decline, the New Right began to show Kissinger the door in the late 1970s. But Grandin explains that Kissinger’s defense of the Vietnam War and his arguments for escalation into Cambodia had already become deeply embedded in the ideology of Republican establishment. While Reagan distanced himself from the Secretary of State during his 1976 presidential primary campaign, by 1980 Kissinger was back speaking at the Republican National Convention.

Kissinger’s legacy in the realm of diplomacy is the focus of the book’s second half. Looking at other parts of Asia, Grandin examines his encouragement of the Indonesian invasion of East Timor and his ambivalence towards selective genocide in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Turning to Africa, he exposes in great detail Kissinger’s support for apartheid governments, and in terms of the Middle East, he blames him for locking the United States into a perpetual crisis by vehemently pursuing American hegemony in the region. Kissinger’s impact was global, spanning “from the jungles of Vietnam to the sands of the Persian Gulf.”

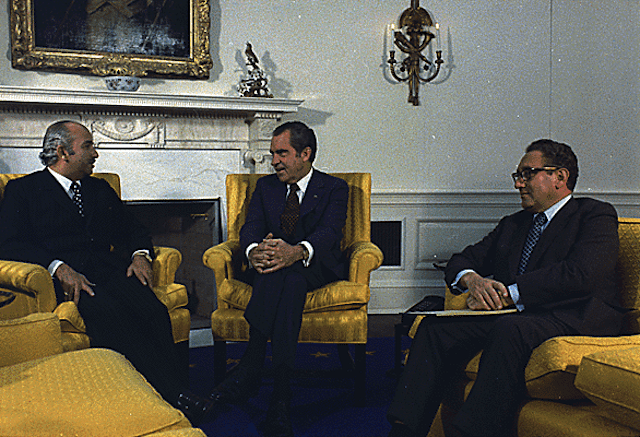

Meeting in the Oval Office between Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger, and Egyptian Foreign Minister Ismail Fahmi, 31 October 1931. Via Wikipedia.

Grandin’s most interesting chapter is domestically focused and intellectually based. The Church Committee inaugurated a new era of foreign policy oversight that Kissinger described as “a merciless congressional onslaught.” Congress’ season of inquiry into matters of national security during the 1970s produced a new relationship between secrecy and spectacle. According to Grandin, the spectacle of continuous congressional hearings nullified the need for secrecy partly because oversaturation leads to public indifference. And when important controversies become mere visual entertainment, public attention fades as crimes are turned into procedural questions or differences of opinion between political parties. Further confusing the issue, arguments over whether the ends justify the means usually leave the hawks in Congress in agreement, and so for the general public such inquiries often act to justify both sides. For his contribution, Kissinger is described as a master at reframing controversial policies into technical matters. But Grandin’s conclusion that Kissinger decided to go covert with the coup against Allende in Chile because Congress was breathing down his neck over Vietnam seems circumstantial. Still, his insight into the parallel nature of secrecy and spectacle fits well anecdotally – in the following decade, Reagan’s full-scale invasion of Grenada smacks as a distraction from the covert wars being carried out in Central America.

Kissinger’s Shadow connects the sustained American militarism and the increased political polarization that followed the end of the Cold War. Grandin convincingly argues that Kissinger’s influence on U.S. foreign policy has reverberated into the twenty-first century. While he might rely too heavily on a career’s worth of Kissinger’s writing as ammunition to attack him with, the author’s bias against the now elder statesman does not nullify the facts that he presents and most of his interpretation of those facts. The support that many Americans continue to give to a broad policy of intervention and perpetual war may have started out as a product of the superpower rivalry, but Kissinger’s enduring popularity has allowed such machinations to transcend the Cold War.

Greg Grandin, Kissinger’s Shadow: The Long Reach of America’s Most Enduring Statesman (Metropolitan Books, 2015).

You may also like our collection of essays on US Presidents and Mark Battjes’ recent review of David Milne’s Worldmaking: The Art and Science of American Diplomacy (2015)