by Carolyn Pouncy

Everyone loves to be proven right, but novelists don’t often expect it—especially five hundred years after the period where their books are set. After all, that’s half the fun of writing and reading fiction: filling in the gaps left by the historical record. So to have a set of novels that explore the relationship between Russians and Tatars in the sixteenth century twice intersect with contemporary developments is surprising.

The first conjunction, as I wrote on this blog last summer, involved the publication of my Winged Horse in the same month that Vladimir Putin decided to annex Crimea. That might be considered a historical accident. The second overlap is quite different: as I discovered not long ago, twenty-first-century science supports my imaginary past in a remarkable way.

First, a brief review of the history. After Grand Prince Vasily III died late in 1533, the situation in Russia deteriorated fast. The hand-picked council of guardians Vasily appointed was pushed aside within months by his widow, Elena Glinskaya. Despite threats from without and within, Elena maintained a shaky hold on power until her sudden death in April 1538 left the country under the nominal authority of her seven-year-old son, the future Ivan the Terrible. Several aristocratic clans, most notably the Shuisky and Belsky princely families, battled to control the young grand prince until 1547, when he married and was crowned as Russia’s first tsar.

Because Elena was no more than thirty when she died, the gossips had a field day speculating about the cause of her death. Even before that, Elena’s morals, or lack thereof, had attracted considerable attention, inside and outside Muscovy. Rumors included assertions that her chief adviser, Ivan Telepnev, had fathered her two sons during her husband’s lifetime, that he retained his status as her lover after Vasily’s demise, and that she had hired Sami shamans to ensure successful pregnancies with these children of questionable heritage.

Once Elena usurped a role normally reserved for men, the hostile whispers intensified. The campaign that she and Telepnev waged against her two brothers-in-law and her uncle Mikhail fed the flames, especially after the brothers-in-law and uncle died in captivity between August 1536 and December 1537. A mere four months passed between the death, reputedly by starvation, of the younger brother-in-law and Elena’s demise.

The favorite story about her death involved her having been poisoned by the Shuisky clan, whose leader Vasily promptly clapped Telepnev in irons and within three months had married a cousin of the young grand prince, a classic power move that indicated possible self-positioning for a grab at the throne. But there has never been concrete evidence that a murder took place. When a group of twentieth-century scientists excavated the bodies of Elena and other royal figures—including Ivan the Terrible’s first wife, Anastasia, also rumored to have died from poison—they found high levels of dangerous substances such as mercury and arsenic. But because mercury was used in medicines at the time and arsenic in cosmetics, the scientists refused to confirm the poisoning hypothesis.

As a historian, I hesitate to charge actual historical figures with a crime without clear proof of guilt, even in a novel and five centuries after the fact. Nevertheless, in the absence of evidence novelists do get to invent plausible explanations, so long as they confess their sins at the end. And nothing spices up a novel faster than romance and murder. So in The Shattered Drum (Legends of the Five Directions 5: Center) I invented an elaborate plot that played on all the rumors about Elena’s affair with Telepnev, her death, and the clan politics surrounding it, then assigned the implementation to a trio of fictional characters representing the opposing sides. The novel came out last summer, and I chalked it up as complete and moved on to the next, which incorporates another recent discovery: spy chambers in what was then the outermost wall surrounding Moscow.

Elena Glinskaya: Forensic facial reconstruction by S. Nikitin, 1999 (photo credit: Shakko CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

Then I learned that the story was not, in fact, over. A group of Kremlin Museum scientists has re-exhumed the bodies of the various grand princesses once buried in the Ascension Cathedral in the Kremlin. They published their results, almost all of which are fascinating when disentangled from the minutiae of archaeological recording—especially in reference to Elena Glinskaya.

Most notably, the plot point that I considered the most outrageous—that Elena not only had an affair with Telepnev but became pregnant with his child, a scandalous development for a woman whose husband had died four years before—turns out to be well within the realm of possibility. The contemporary scientists discovered that, as noted above, Elena’s bones contained high levels of mercury and arsenic. In addition, they found formations in her skull that suggested she had ingested poisonous mushrooms. But her bones also contained unusually low levels of iron, which the scientists attributed to her having suffered a massive hemorrhage not long before her death—probably in childbirth. Indeed, two infant bones were found in her sarcophagus: the tibia of a newborn or infant not more than two months old, and the other an upper jawbone of a six-month-old.

There were other strange objects in the sarcophagus: broken pottery and the bones of pigs and cattle. The scientists didn’t explain these, anymore than they explained the presence of bones from two infants. But they did conclude, quite emphatically, that Elena died of mercury poisoning and that not long before she died she bore a child—fathered, they assume, by Ivan Telepnev. They don’t identify the culprits in her murder, but if we apply the principle of cui bono (who benefits), it doesn’t look good for the Shuisky clan.

It’s a cliché to say that truth is stranger than fiction, but clichés become clichés for a reason. I like to think my solution is a little more elegant, although you’ll have to read the novel to find out what that is. But the astonishing part is to discover that something I’d written off as pure invention has a basis in truth after all.

And oh yes, the scientists think Anastasia died of mercury poisoning as well. Maybe I’ll write that novel, too, one day. But if I do, I’ll be very careful about what I make up.

Originally posted as “Person or Persons Unknown,” on the Blog of the NYU Jordan Center for the Advanced Study of Russia (December 19, 2018).

Carolyn Pouncy, the managing editor of Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History, writes fiction set in sixteenth-century Russia under the pen name C. P. Lesley.

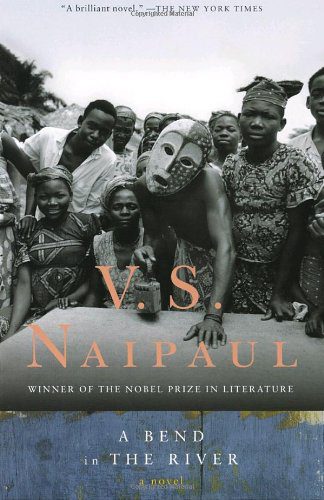

Much like its eponymous waterway, V.S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River meanders steadily through the dark reality of postcolonial Africa, alternately depicting minimalist beauty and frightening tension. Like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, subtle prose reveals the timelessness of the continent’s remote corners alongside human corruptibility. Yet, Naipaul moves his narrative closer in time to contemporary Africa, demonstrating that the horrifying legacies of colonialism did not end with Europe’s retreat. In A Bend in the River, the struggle to establish national identities in the wake of Western imperialism takes center stage, with “black men assuming the lies of white men” in order to govern.

Much like its eponymous waterway, V.S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River meanders steadily through the dark reality of postcolonial Africa, alternately depicting minimalist beauty and frightening tension. Like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, subtle prose reveals the timelessness of the continent’s remote corners alongside human corruptibility. Yet, Naipaul moves his narrative closer in time to contemporary Africa, demonstrating that the horrifying legacies of colonialism did not end with Europe’s retreat. In A Bend in the River, the struggle to establish national identities in the wake of Western imperialism takes center stage, with “black men assuming the lies of white men” in order to govern.