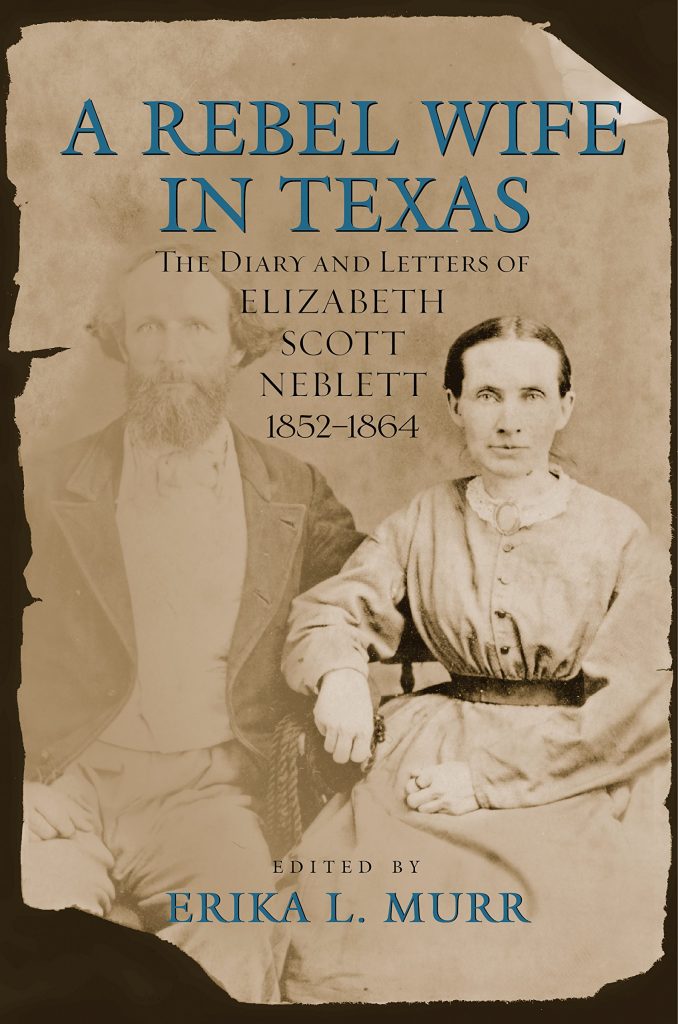

In 2001, many of Lizzie Scott Neblett’s diaries and letters were published in a volume entitled A Rebel Wife In Texas. The text provides a harrowing glimpse into the desperation, brutality, and minutiae of everyday life in antebellum Texas from the perspective of a landed, slaveholding, Southern wife. Letters written to Neblett prior to her May 25, 1852 wedding to aspiring attorney William H. Neblett, however, lend an entirely different type of insight into the “rebel wife’s” intimate affairs, one that unearths a wealth of decidedly queer complexity.

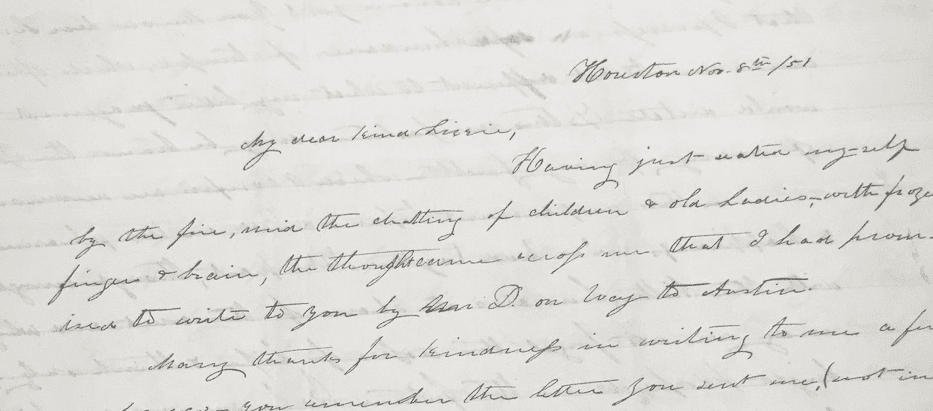

The bulk of these missives were penned by sisters Sallie and Amanda Noble, childhood friends of Neblett residing at the time in Houston. Much of the correspondence between the Noblewomen and Neblett gestures toward an increasingly sapphic sociality. On September 12, 1851, for instance, Sallie writes to Neblett to divulge that she “was feeling in a funny mood [that] morning [and] could think of no better business than to trouble [Lizzie] with a few of my funny thoughts . . . . I told Amanda a few minutes ago that . . . I was going to do just as I pleased [and] I did not care what people said [or] thought…Did you ever have such feelings Lizzie?” Noble does not elaborate on just what kinds of things she intended to “do . . . as [she] pleased,” but later in this same letter, Sallie assures Neblett that despite persistent rumors that she is soon to be wed, “I have not the most distant idea of getting married soon.”

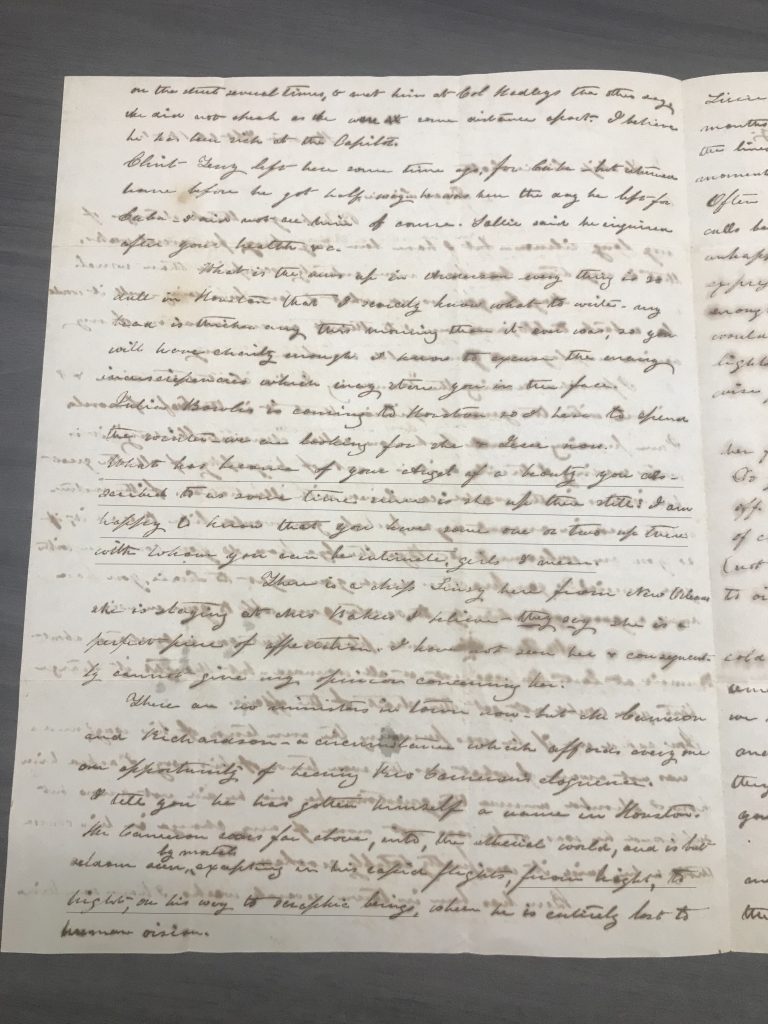

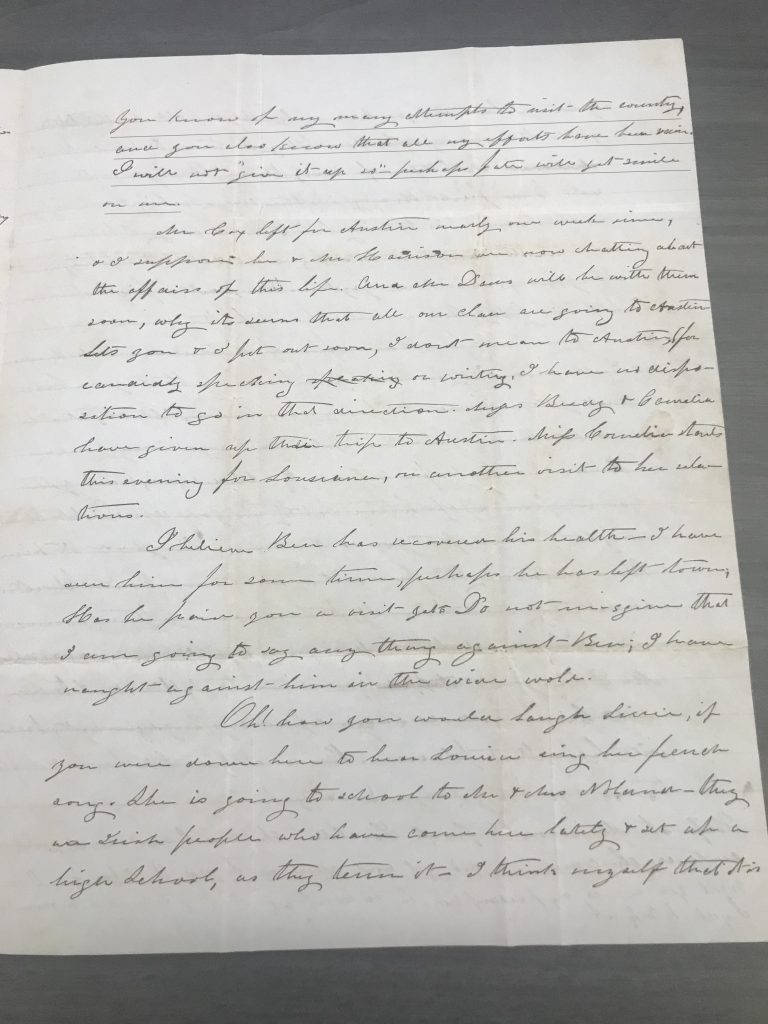

Ten days later, Sallie’s sister Amanda sends Neblett a note inquiring “what [had] become of [the] Angel of a beauty you [Lizzie] described to us some time since. Is she up there [in Anderson] still?” before adding, “I am happy to know that you have some one or two up there with whom you can be intimate, girls I mean.”

While both messages suggest something of a queer kinship between long-time companions, with the Nobles detailing their own disinterest in the prospect of marriage and asking after Lizzie’s Anderson dalliances, Amanda’s letters, in particular, indicate that she and Neblett’s relationship may have constituted what we might now term a romantic friendship. This is evident beginning with Noble’s July 14 admission that “many many have been the times that I’ve wished myself in Anderson with you [Lizzie]—how we would ramble and frolic through the woods—leave our clothes off of us, and many other amusing things, which would be a sunny spot in our lives.”

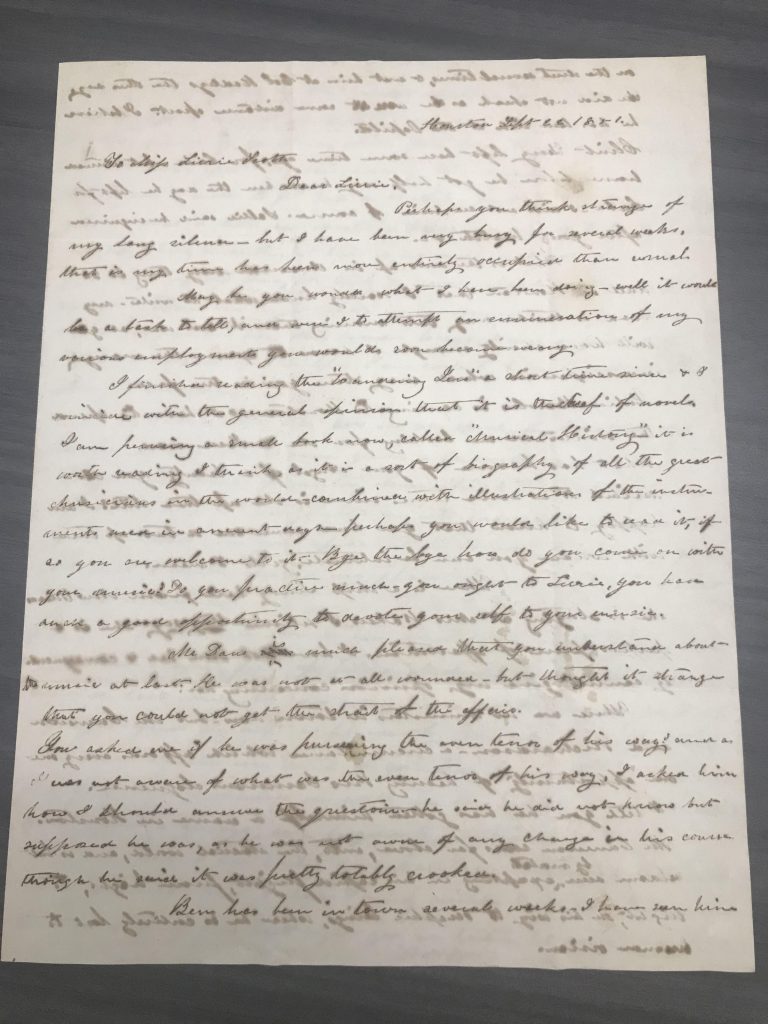

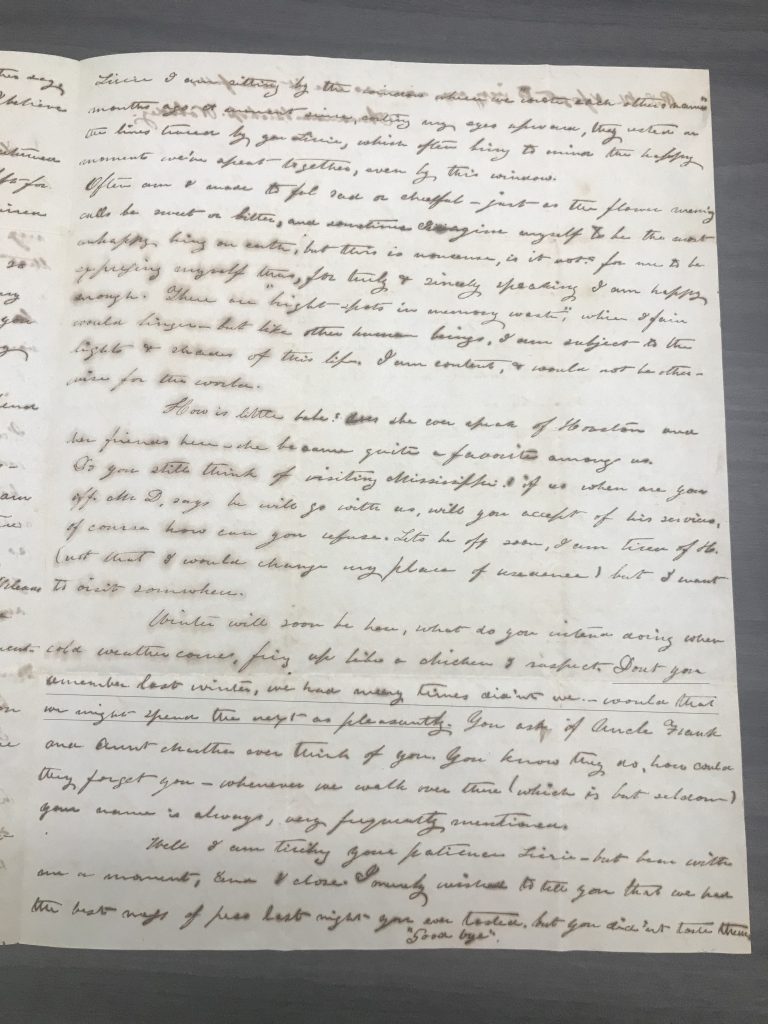

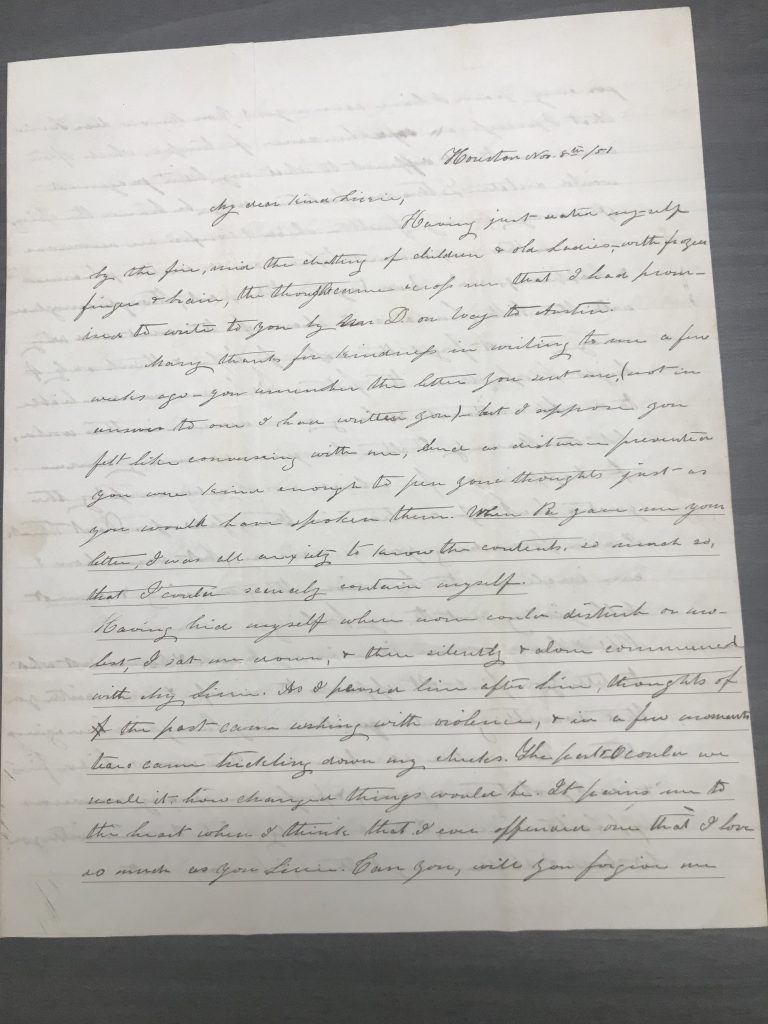

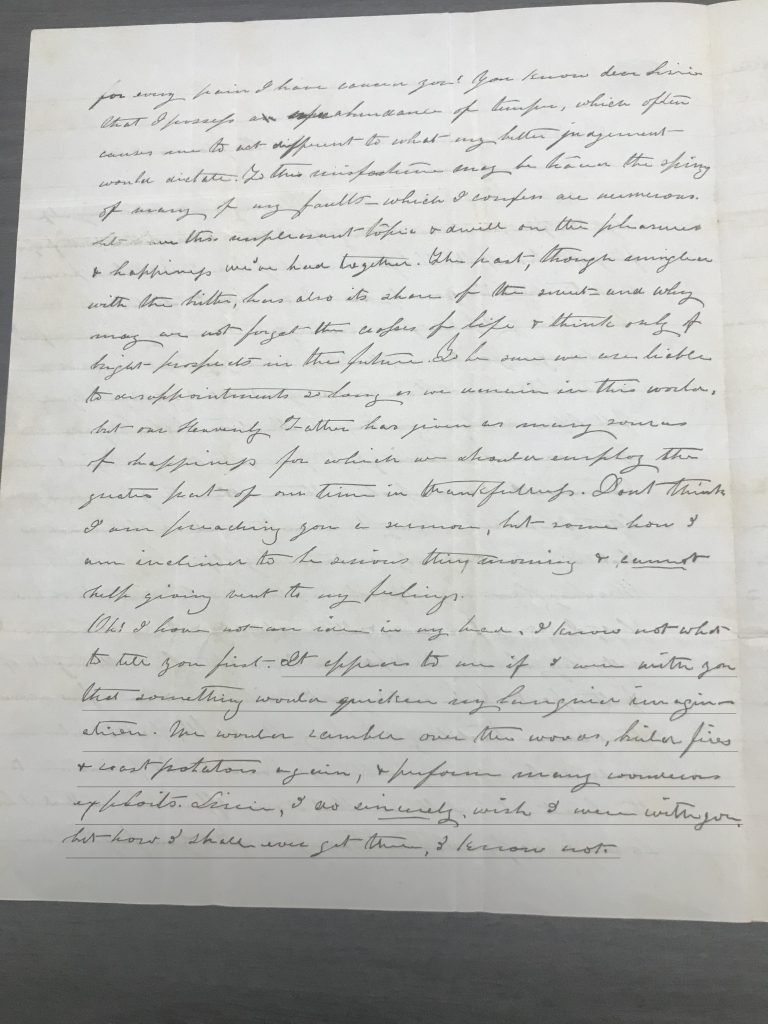

The tone of Noble’s dispatches becomes more clandestine near the close of 1851. On November 8, Amanda wrote to report that, “when Pa gave me your letter, I was all anxiety to know the contents, so much so, that I could scarcely contain myself. Having hid myself where none could disturb or molest, I sat me down, and there silently and alone communed with my Lizzie.” This desire for seclusion is reflected in Noble’s decision to sign this letter simply “A.,” though similarities in handwriting and content between this and previous writings confirm Amanda as its author. The rest of the missive seems to reveal that the two women have had some kind of falling out. Noble writes “As I perused line after line [of Lizzie’s last communication], thoughts of the past came washing with violence, and in a few moments tears came trickling down my cheeks…It pains me when I think that I ever offended one that I love so much as you Lizzie.” Amanda admonishes her friend to “dwell on the pleasures of happiness we’ve had together” rather than her bouts of temper, and adds that “the past, though [infused] with the bitter, has also its share of the sweet.”

Revisiting her earlier fantasy, Noble tells Neblett that “it appears to me if I were with you that something would quicken my languid imagination. We would ramble over the woods, build fires, and roast potatoes again, and perform many wondrous exploits. Lizzie, I so sincerely wish I were with you, but how I shall get there, I know not . . . I will not ‘give it up so’—perhaps fate will yet smile on [us].”

It is unclear, though, whether that was to be the case. Shortly after the writing of this letter, Lizzie was wed and embarked on a new, ultimately trying chapter of her life—marked by war, motherhood, violence, and loss. And, despite earlier protestations to the contrary, the years following Lizzie’s marriage found both Sally and Amanda Noble following suit, with the former marrying a John Kennard in 1855 and the latter marrying Henry White in 1856. Years later, however, Neblett still seemed to maintain a nostalgic fondness for the confidantes of her maiden days, journaling of a sick and seemingly dying Amanda in 1863, “she is not long for this world—[but] she ought to live, for she has always managed to extract much sweetness from life.”

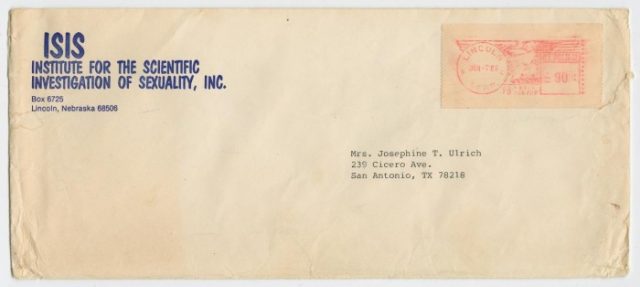

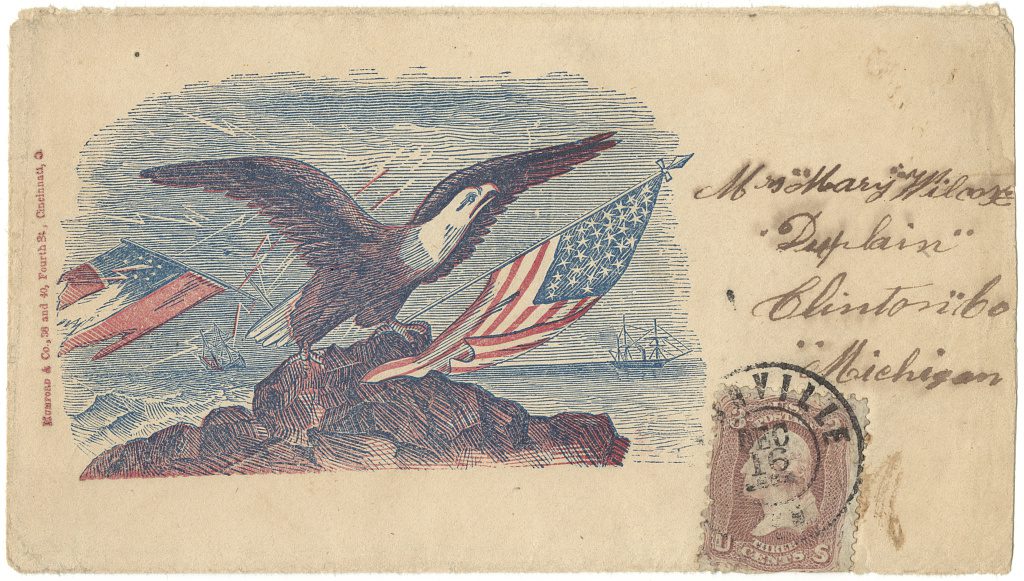

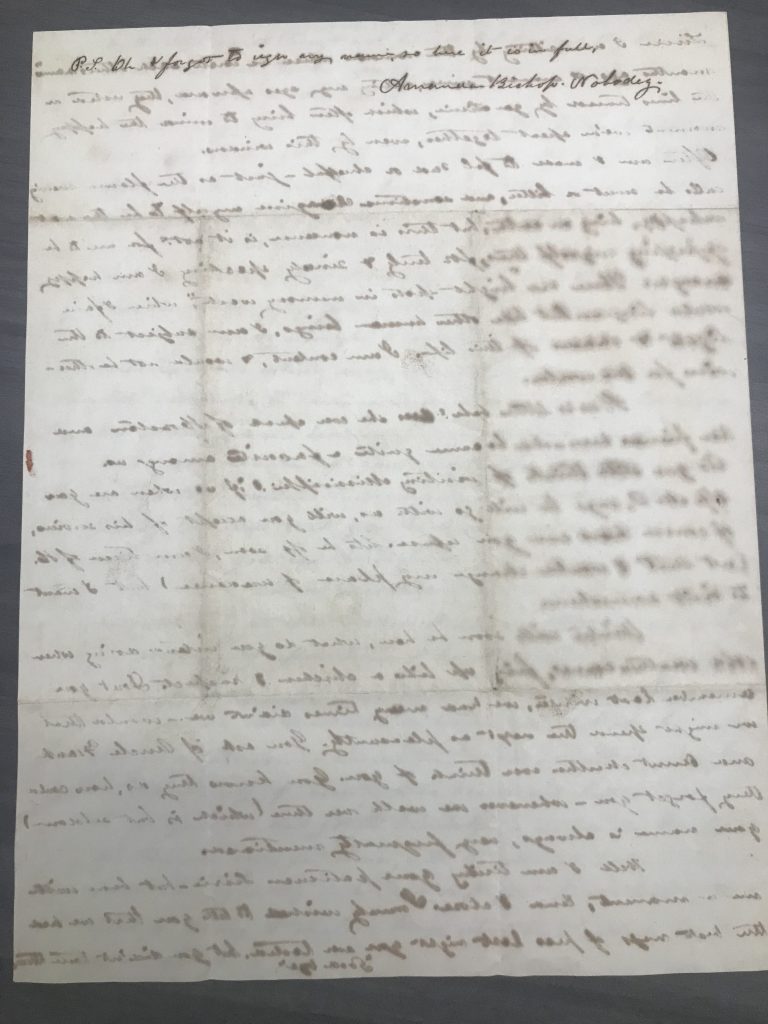

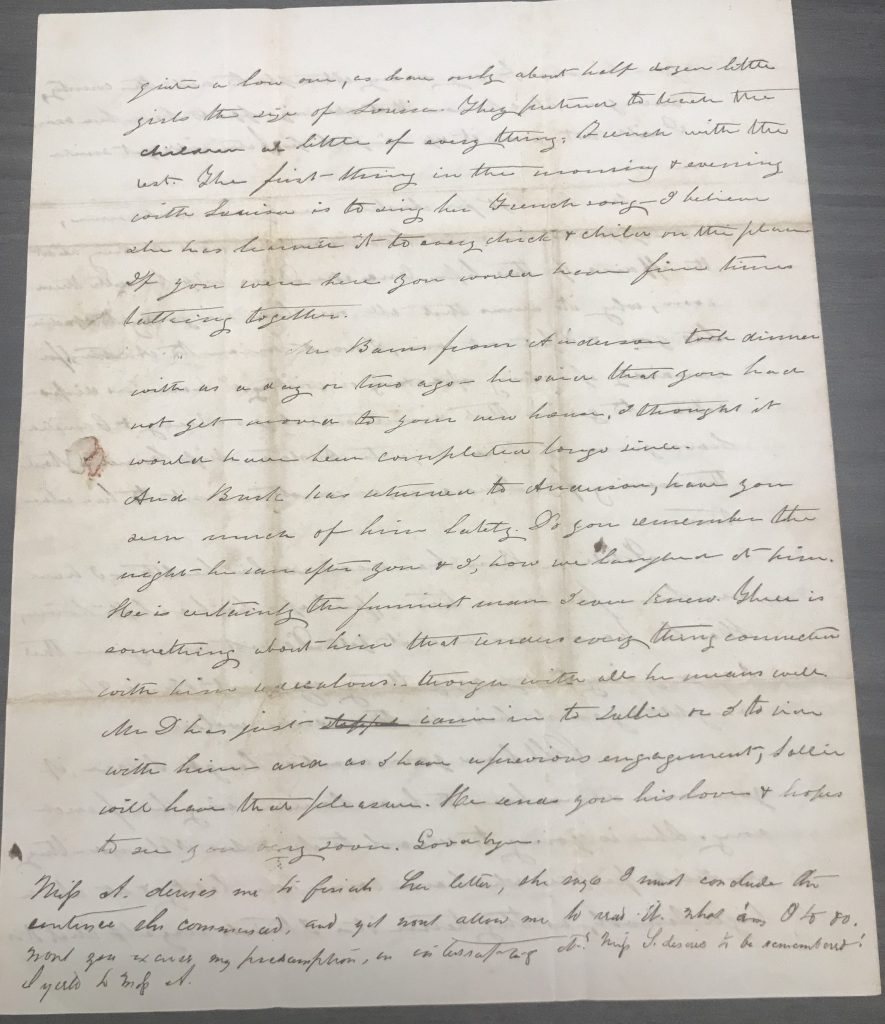

Gallery of Neblett and Noble’s Letters via the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History

Bibliography

- A. to Lizzie Scott, November 8, 1851, Lizzie Scott Neblett Papers, 1848-1935, Box 2F81, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

- Benowitz, June Melby. “Neblett, Elizabeth Scott.” Handbook of Texas Online. Accessed February 11, 2020: https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fne28.

- Neblett, Elizabeth Scott, and Erika L. Murr. A Rebel Wife in Texas: The Diary and Letters of Elizabeth Scott Neblett, 1852-1864. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001.

- Noble, Amanda to Lizzie Scott, July 14, 1851, Lizzie Scott Neblett Papers, 1848-1935, Box 2F81, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

- Noble, Amanda to Lizzie Scott, September 22, 1851, Lizzie Scott Neblett Papers, 1848-1935, Box 2F81, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

- Noble, Sallie to Lizzie Scott, September 12, 1851, Lizzie Scott Neblett Papers, 1848-1935, Box 2F81, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

You might also like:

Rage and Resistance at Ashbel Smith’s Evergreen Plantation

Rising From the Ashes: The Oklahoma Eagle and its Long Road to Preservation

White Women and the Economy of Slavery

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.