(via flickr)

by Guy Raffa

What is it with baseball players and whiskers?

The 2013 Red Sox perfected the art of beard-bonding on the way to their third World Series championship in ten years. Boston players and their fans rallied around what Christopher Oldstone-Moore calls the “quest beard” in his history of facial hair, Of Beards and Men. Two years later the Yankees began winning only after Brett Gardner stopped shaving his upper lip and, seeking to propitiate the baseball gods, his teammates followed suit. Lip caterpillars soon dwindled along with victories that first year without naked-faced Derek Jeter, but there were still more staches and wins than pundits predicted before the season began. The 2017 Fall Classic featured two rosters—the Houston Astros and Los Angeles Dodgers—modeling a wide assortment of trendy beards, with Dallas Keuchel’s voluminous but well-tended shrubbery taking first-place honors.

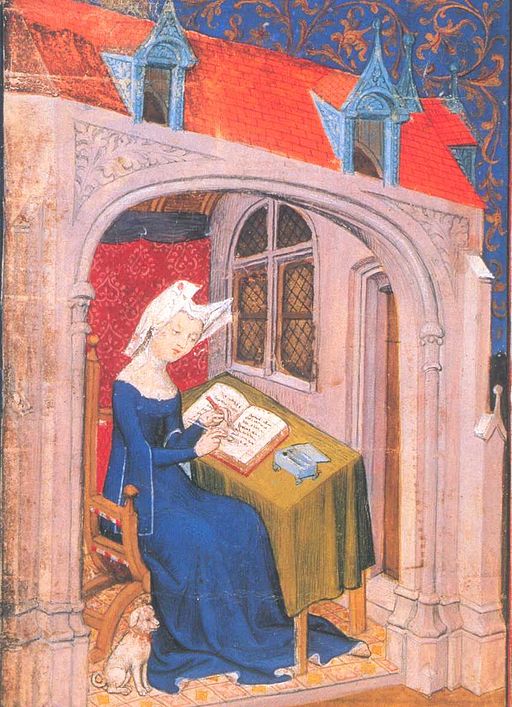

Dallas Keuchel and his beard (via wikimedia)

The Washington Nationals entered this 2018 season determined to supplant the Astros for best overall beard garden, but Houston more than held its own in facial fashion and on the diamond, finishing the year with the second best record. Helped by long-bearded pitchers Craig Kimbrel and David Price, the Red Sox led all teams in victories, pulling away from the mighty yet clean-shaven Bronx Bombers, and could well square off against the Astros in the American League Championship Series for a ticket to the 2018 World Series.

Facial hair has been attached to masculine dominance as far back as the late Middle Ages and the early modern period: “No hairs,” so went the pun, “no heirs.” The trend continues. Adjusting to the new normal of fewer shaves and more beards over the past decade, Procter & Gamble (parent company of Gillette), has sought to increase revenue by marketing styling and grooming products more aggressively.

A recent survey of 8,520 women by researchers at the University of Queensland in Australia found that, while stubbled faces are deemed sexiest, full-bearded men are favored for long-term relationships. Gay men surveyed also respond more favorably to men with facial hair. Another scientific study reveals that bristles make men wearing aggressive expressions appear that much more threatening. Hence the many pitchers who forgo razors the day of the game in search of a predatory advantage over club-wielding scruffs standing sixty feet, six inches away.

Woodcut of Ezzelino III da Romano, unfortunately without the famous nose hair (via wikipedia)

But forget about staring down plain old beards and mustaches. Just imagine having to face the facial hair sported by the medieval warlord Ezzelino da Romano. By facial hair I mean just that, one single strand. This alpha male, a dark and hairy beast of a man, sprouted a single black hair on the tip of his nose, a genetic abnormality that had nothing to do with fashion but made quite a statement nonetheless.

Ezzelino terrorized inhabitants of northern Italian cities and towns in the thirteenth century. A murderous despot, he was said to be responsible for taking over 50,000 lives, on one occasion slaughtering over 10,000 Paduans by fire, sword, and starvation. He was such a bad dude that the pope of the time, Alexander IV, called him “a son of perdition . . . the most inhuman of the children of men” and launched a crusade against him.

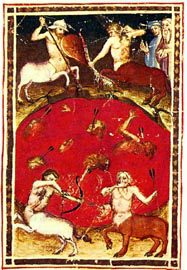

Ezzelino’s nose ornament took hostile facial fuzz to another level. Whenever he became enraged, the long dark hair on his nose immediately stood up, making those around him run for their lives. Anger on steroids. Little wonder that the poet Dante condemned Ezzelino to the circle of violence in his Inferno (canto 12, lines 109-110), placing him with other homicidal tyrants in the Phlegethon, a river of hot blood. Like a meatball in a pot of tomato sauce, a dark head of hair is all that appears of Ezzelino above the bubbling red surface.

Dante and Virgil observe the centaurs shooting the tyrants in Phlegethon. Charles S. Singleton (Inferno XII) (via wikimedia)

Imagine plucking Ezzelino da Romano from Dante’s red river and fitting him in an Astros uniform for game seven of the 2018 American League Championship Series against the Red Sox. There is no score with two outs in the bottom of the ninth inning. José Altuve, Marwin Gonzalez, and Evan Gattis beam their impressive face rugs from third, second, and first base. Pinch-hitting for peach-fuzzed Alex Bregman, Ezzelino steps to the plate and digs in.

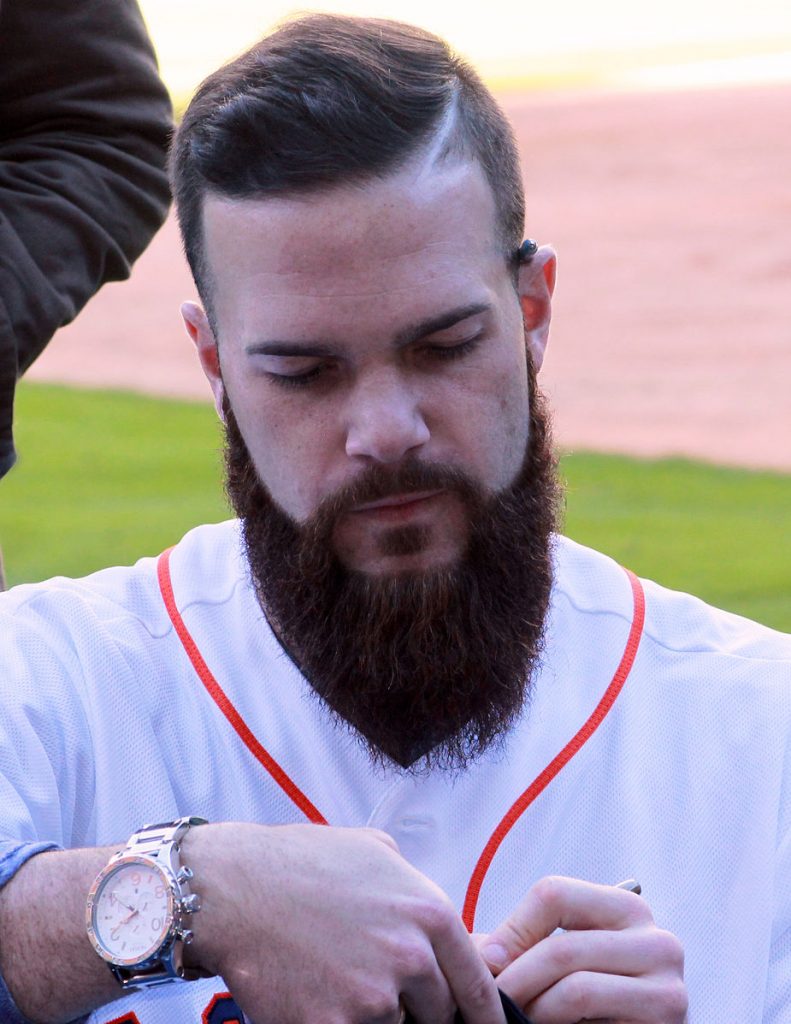

Craig Kimbrel and his red beard (via wikipedia)

Red-bearded Craig Kimbrel gets the sign and checks the runners. Ezzelino waits, his head steady and slightly tilted toward the mound. Kimbrel rocks back, lifts his left leg, and just as his eyes find the target—boing!—Ezzelino’s nose hair snaps to attention, perfectly parallel to the bat in his hands. The terrified hurler uncorks a wild pitch, allowing Altuve to sprint home with the winning run. The Astros are headed to the World Series, while the Red Sox and their fans brace themselves for a long, cold New England winter.

Bibliography:

Will Fisher, “The Renaissance Beard: Masculinity in Early Modern England,” Renaissance Quarterly 54, no. 1 (2001): 155–87, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1262223; Christopher Oldstone-Moore, Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015); Douglas Biow, On the Importance of Being an Individual in Renaissance Italy: Men, Their Professions, and Their Beards (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), 181-224; Giovanni Villani (c. 1280-1348), Nuova cronica, ed. Giuseppe Porta, 3 vols., 2nd ed. (Parma: Fondazione Pietro Bembo, 2007); Dante Alighieri, La Divina Commedia, ed. Giorgio Petrocchi. (Turin: Einaudi, 1975); Benvenuto da Imola (1375-1380), commentary on Inferno 12.109-112, database of the Dartmouth Dante Project, https://dante.dartmouth.edu; Paget Toynbee, A Dictionary of Proper Names and Notable Matters in the Works of Dante (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968).

Beard Links:

Beard bonding: http://www.bostonglobe.com/sports/2013/10/02/beards/BAQGj2IcEckzCq5Z0Piy3N/story.html

Brett Gardner stopped shaving his upper lip:

http://m.yankees.mlb.com/news/article/120449078/for-brett-gardner-yankees-its-not-a-stache-decision

Wide assortment of trendy beards:

Long-bearded pitchers Craig Kimbrel and David Price:

https://www.masslive.com/redsox/index.ssf/2018/07/craig_kimbrels_long_beard_isnt.html

Best overall beard garden:

Fewer shaves and more beards:

https://chicago.cbslocal.com/2018/08/08/909324-beards-bad-gillette-razors/

Early modern period:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1262223?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

A recent survey:

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/17/well/family/are-men-with-beards-more-desirable.html

Another scientific study:

https://academic.oup.com/beheco/article/23/3/481/221987

A river of hot blood:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/35/Inf._12_anonimo_fiorentino.jpg

Other articles you may like:

Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy by Jules Tygiel (1997)

Baseball by the Numbers: Moneyball (2011) by Tolga Ozyurtcu

The Enduring Chanel: Reaction to a Revolutionary Reformer of Women’s Fashions by Leila Bonakdar, Kate Chen, Jessica Salazar, and Lauren Todd