By Jesse Ritner

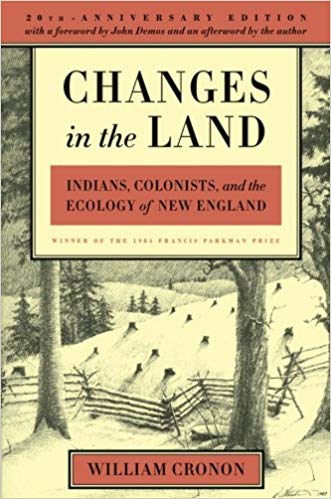

Thirty-five years ago William Cronon wrote Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. It has aged well. The continued relevance of the book is likely a result of two things. First, it is eminently readable. Flipping through the pages, one can imagine the forests that Cronon describes and feel his connection to them. Second, the problem he poses about the limits of disciplinary work in writing the history of environmental change are more poignant now than ever before, as humanists across disciplines attempt to write to current concerns about climate change and the relationship between humans and nature. Cronon argues that the cultural and ecological consequences of colonization are deeply connected. As such, they demand the tools of both a historian and an ecologist. He traces the process by which Indigenous communities and European communities made meaning of the environment to the ecological changes that resulted from the influx of a new culture. His book is not meant to suggest a single material cause of conflict, but looks at how cultural histories of diverse issues – such as land acquisition, the development of capitalist economies, the growth of towns, and the fur trade – can benefit from studying the relationship between human action and ecological consequence.

Cronon offers transparency about his methods and sources as well as any other author. He begins his book with an explanation of what ecological sources might be for a colonial history of New England. He pinpoints four varieties: naturalists’ accounts written by early colonists and their ancestors, town records that register disagreements over ownership and property, the work of historical ecologists, and then what he terms “interpolations,” which use modern ecological literature to assess the probability of past change. By looking at these materials together, Cronon demonstrates that changes in people’s livelihoods and the means of production are not simply social, but are often dependent on ecological changes. As a result, his book is not about two landscapes, one before colonization and one after, but about two different ways of belonging to an ecosystem.

Following his discussion of methodology, Cronon moves on to explore the relationship between property ownership and human interactions with ecosystems. He begins by analyzing the diversity of New England woodlands in the pre-colonial era. He makes a clear distinction between the northern and southern halves of New England, determined mostly by the lack of agriculture further north. This created a different relationship to property and different modes of production for northern Indians. As a result, the makeup of the forests was different. Different modes of production also occurred, however, as a result of different relationships to seasonality. Cronon argues that European conceptions of poverty often disguise the importance of seasonal practices to Indigenous peoples. This has also led to a false perception that European societies do not also adjust their work and technologies to the seasons. Mobility was central for Indigenous populations, who hunted, fished, or farmed depending on the season. In contrast Europeans relied on storing food over the cold winters. This demanded a type of non-mobile settlement that was previously uncommon in New England. Cronon contends that the conflict over seasonality, not over a specific resource, was the root of European and Indigenous conflicts. The role of stability in European seasonality necessitated the creation of a new property regime in New England that limited Indigenous abilities to interact with the ecosystem and profoundly changed the land. In his estimation we live today with the consequences of this new property regime.

In the final parts of the book, Cronon looks at the fallout from this conflict through the commodification of furs, trees, and livestock. In each of these cases. Cronon shows that transformations of property regimes and the effects these transformations had on the ecosystems surrounding them were a process, rather than an immediate change. Through examining this process, he deconstructs the development of European property regimes, the commodification of resources, and the changes in both European and Indigenous means of production. The most notable result of these changes was the destruction of “edge areas” that were home to diverse flora and denser populations of fauna. These “edge areas” gave the woods the park-like appearance that early naturalists encountered in New England and that Thoreau mourns the loss of in Walden.

There are moments when the age of Cronon’s book shows. The lack of local ecological specificity, the omission of variations in specific Indigenous communities, and the overshadowing of violence and direct human conflict by broad ecological changes all demonstrate that the politics and principles of writing Native American histories have changed in the past few decades. Yet, the connections that Cronon draws powerfully denaturalize the idea that humans exist outside of nature. The clarity of his argument, and the pleasure of reading his work allow this book to maintain its place as a staple in everything from undergraduate introductory classes and grad-student seminars on Native American and Environmental histories, to bookstore shelves, and as a gift for friends and relatives who love history and camping. Few books are so intellectually satisfying and casually readable at the same time. For this reason, and many more, Cronon’s book will continue to worth reading in years to come.

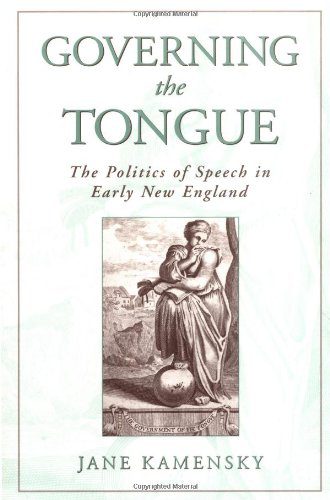

Kamensky argues that early settlers were uniquely preoccupied with the act of speech and held to specific but unwritten rules about correct speaking. Speech was bound up with

Kamensky argues that early settlers were uniquely preoccupied with the act of speech and held to specific but unwritten rules about correct speaking. Speech was bound up with