From her probable origins on a floating brothel in Canton, Zheng Yi Sao became one of the most formidable figures in East Asian piracy, commanding around 70,000 pirates at the peak of her power.[1] Due to a number of factors, including a general scholarly neglect of East Asian piracy in China and the emphasis placed on her husbands, Zheng Yi and Chang Pao,[2] Zheng Yi Sao has only recently become a topic of significant interest. Though women’s participation in piracy was by no means rare in her time, Zheng Yi Sao is an especially fascinating figure because she was able to weave through social conventions and amass a remarkable level of influence not just relative to other women but relative to other pirates in a society that at least nominally emphasized Confucian views of female domesticity.[3] This article traces how Zheng Yi Sao adapted contemporary roles available to women as a strategy for advancement and argues that her ability to do so enabled her to shift the balance of power for herself throughout her life.

Piracy is inherently performative, as projecting either an extremely violent image or markers of gentility and statehood allowed pirates to retain power through reputation. Recent developments in gender studies and anthropology also recognize performativity as intrinsic to gender, acknowledging that participation in certain gendered roles, institutions, and norms constitute a “performance” of one’s gender and the expectations associated with it.[4] Zheng Yi Sao’s performance of gender is interesting as it intersects with what initially appears to be a conflicting performance of piracy. As a woman in Confucian society, she gained power partly from marriage and widowhood, while simultaneously leading an organization known for employing terror tactics and extreme brutality. This is not to say that Zheng Yi Sao’s participation in gendered forms was always strategic but it was undeniably a strong influence. She was a masterful leader who wound her way in and out of social convention, selectively choosing when to obey gendered expectations and when to ignore them. Thus, she offers a unique glimpse into how her gender performance intersects with the performative nature of piracy and how that ultimately played a role in her success.

On The Margins

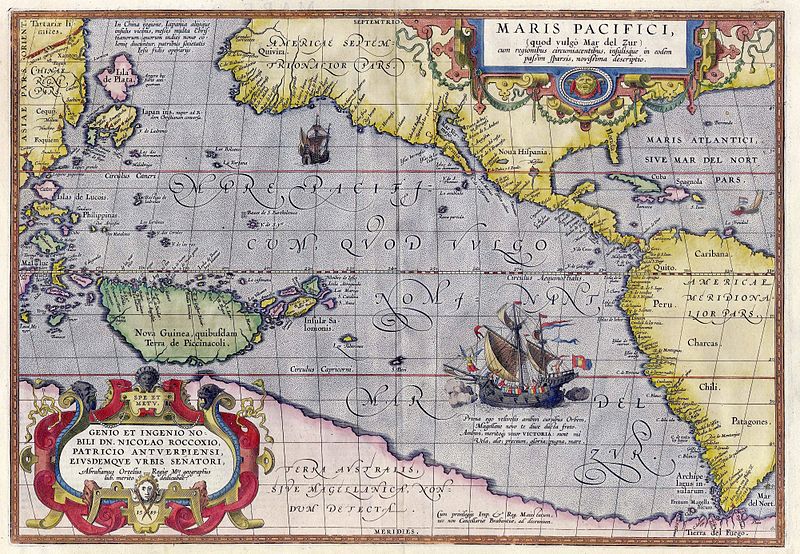

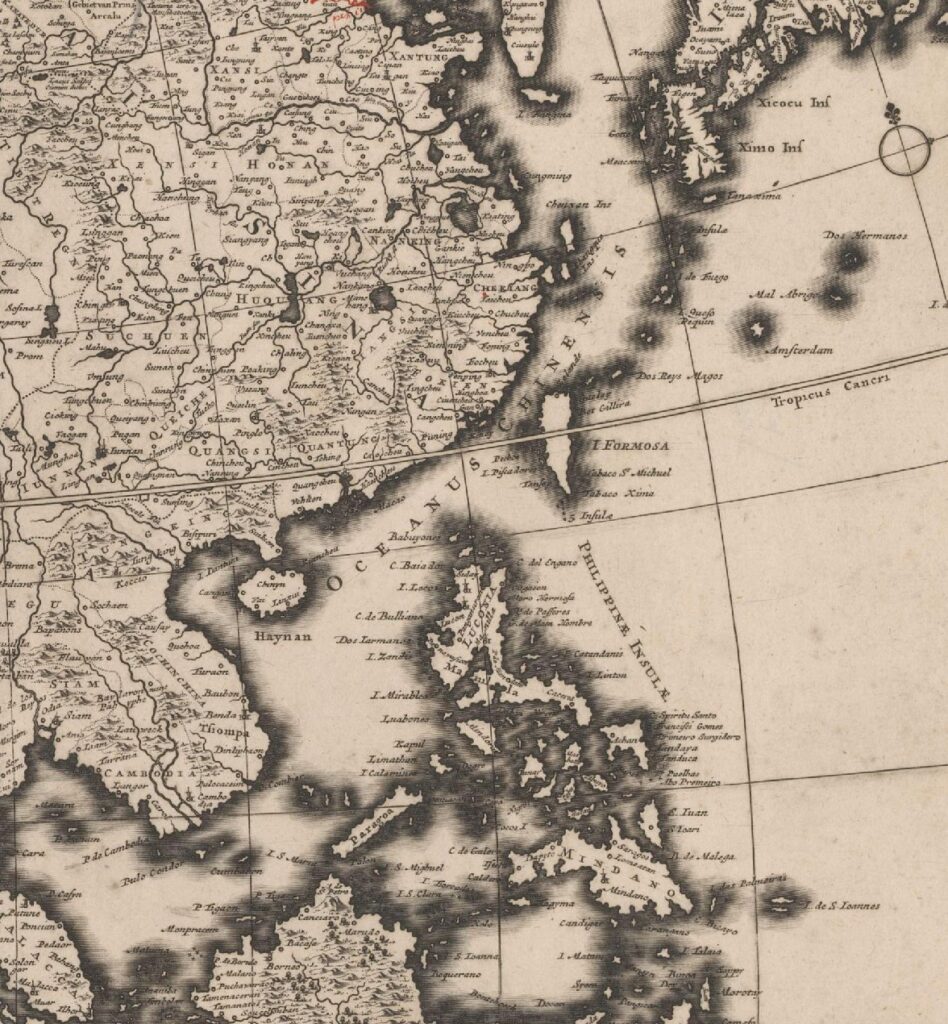

Personal details about Zheng Yi Sao are scarce. She was born in Canton around 1775 and was likely trafficked into sex work.[5] Scholar Nathan Kwan has argued that South China in particular lent itself to female involvement in piracy because it was a place where many marginalized groups resided outside mainstream Han culture.[6] This gave women the opportunity to break out of conventional norms and pushed people of all genders to turn to piracy under economic and political strain. Following the Opium War and the incursion of foreign powers into the region, economic deprivation and political upheaval deeply impacted the South China coast and pressured coastal communities. Women often worked on ships or in jobs related to maritime life, or were sex trafficked and worked on floating brothels called “flower boats.” [7] Given the context in which Zheng Yi Sao lived and worked and the significant presence of minority groups in southern coastal communities, perhaps the best way to understand this figure is as a person on the margins.

These origins provide a point of departure for understanding how Zheng Yi Sao entered into the world of piracy and highlight how her gender may have played a key role in facilitating that entry. It was Zheng Yi Sao’s connection to maritime life as a sex worker that shaped and gendered her interaction with piracy.[8] Crucially, unlike some of the other moments in her career where Zheng Yi Sao participated in gendered arrangements to gain power, this was likely not a choice, given the widespread prevalence of sex trafficking in the region. Simply because sex work was important to her entrance to piracy does not mean that the work was inherently empowering. Zheng Yi Sao met Zheng Yi through this work. Though embellished European accounts offer speculative and hypersexualized depictions of their meeting that provide little factual value, it is clear that Zheng Yi Sao’s role as a sex worker brought her into frequent contact with pirates, ultimately resulting in her marriage to Zheng Yi in 1801.[9]

Marriage and Widowhood

Though Zheng Yi Sao may not have chosen to be a sex worker, her transition from this role to a wife exemplifies how active participation in marriage, a gendered institution, provided her an escape from sex work and a foundation from which to build influence in the maritime world. Zheng Yi held significant power among pirates operating in Tây Sơn Vietnam. From 1792 to 1802, the Tây Sơn rulers made the Vietnamese Coast a hotspot for Chinese piracy. Because of political tensions in Vietnam, groups of pirates were typically able to secure sponsorship as privateers and their activities flourished. However, piracy in the region collapsed alongside Tây Sơn rule in 1802, at which point pirate activities shifted to the Chinese coast.[10] Zheng Yi Sao and her husband led the new, smaller pirate gangs, still reeling from the collapse of pirate activities, forming seven fleets commanded by leaders loyal to the family, thus establishing their Guangdong Confederation as the dominant Chinese pirate group.[11]

At this point, we can begin to understand how the merging of piratical leadership with the gendered “wife” role—regarded as essentially subservient in Confucian China—became an advantage for Zheng Yi Sao. Charlie Harris argues, for example, that due to limited paths for women’s upward mobility, Zheng Yi Sao’s marriage to Zheng Yi was likely a deliberate exercise of agency, not merely an “extension of her status as a second-class citizen.” [12] He emphasizes that although Zheng Yi Sao participated in a patriarchal marriage, she was never Zheng Yi’s “accessory [but] rather… his business partner.” [13] Once married, Zheng Yi Sao used her position as Zheng Yi’s wife to actively participate in efforts to gain power and influence over the maritime world. Dian Murray, the foremost scholar of Zheng Yi Sao, describes her as a true partner to her husband in the consolidation process:

Cheng I [another name for Zheng Yi], aided by his wife, met the crisis [in Vietnam] by leading the pirates to re-establish their power across the border in China…While [Zheng Yi] was the unifier and patriarch, his wife was consolidator and organizer.[14]

By 1804, the Guangdong Confederation numbered 400 ships that were home to 70,000 pirates.[15] In a sense, Zheng Yi Sao’s ability to access power through working with her husband on the consolidation of gangs was not unheard of: elite Chinese women did, on multiple occasions throughout Chinese history, gain influence through their marriages or their sons. These still remained “extraordinary cases where ambitious and socially well-connected women were able, as a direct result of their marriages, to manoeuver their way to power within the male-dominated official bureaucracy.” [16] Yet Zheng Yi Sao’s was far from elite, and non-elite women who succeeded in gaining a degree of power usually only exercised that influence “within their homes.” [17] She therefore wielded the power obtained from her marriage with unconventional strength and independence as a woman from a marginal background, turning her marriage into a political opportunity.

Even after her first husband’s death in 1807, Zheng Yi Sao continued to push the conventional pathways to power for Chinese women, leveraging gendered positions as a foundation for dominance. Widowhood offered Zheng Yi Sao a window of opportunity to seize control of the organization she and her husband had built.[18] The crucial component of Zheng Yi Sao’s takeover of the Guangdong Confederation lay in her relational power. Upon her husband’s death, Zheng Yi Sao began to “create and intensify the personal relationships that would legitimize her in the eyes of her followers” and “carefully [balance] the factions around her, building on the loyalties owed to her husband and making herself indispensable to each.” [19] The explicit use of her relationship to Zheng Yi paired with her own strategic abilities yet again demonstrates how Zheng Yi Sao integrated gender into her strategy for ascent, using marital status and diplomacy in tandem.

Zheng Yi Sao’s second marriage presents another revealing case study of her ability to simultaneously use and break marital norms to solidify her influence. By marrying her adoptive son Chang Pao and strategically installing him as leader of the powerful Red Fleet, she “ultimately secured her position at the top of the pirate hierarchy,” while departing from marital norms by breaking the taboos around incest and the remarriage of widows.[20] Following her retirement, her relationship to Chang Pao would once again prove a taboo-breaking method of gaining status when she claimed the benefits of his military title, despite laws against remarried widows claiming the titles of their second husbands.[21] This marriage seems to have been an explicitly strategic choice, since Zheng Yi Sao’s decision to initiate a sexual relationship with Chang Pao came after she installed him as the Red Fleet commander.[22] Scholars who have studied this relationship concur that Chang Pao became a conduit through which Zheng Yi Sao could exert influence over the Confederation. Both Laura Duncombe and Charlie Harris, for example, cite the establishment of harsh legal codes on the Confederation’s ships as a crucial element in Zheng Yi Sao’s consolidation of power. These were codes she implemented through Chang Pao, using his leadership position to legitimate them.[23] In fact, Zheng Yi Sao’s leadership was so effective that marriage to Zheng Yi Sao clearly provided her husband with upward mobility, turning the contemporary relationship between marriage and political power on its head.[24]

Power, Codified

Zheng Yi Sao was undoubtedly the driving force behind the Confederation’s success. The establishment of protection rackets, investment in on-land enterprises, an aggressive military structure, and the power to negotiate with Chinese officials all demonstrate the professionalization of the Confederation under her leadership.[25] She was responsible for the financial affairs of the Confederation and set up the tax offices and protection rackets that allowed it to shift into a state-like entity.[26] This professionalizing process allowed Zheng Yi Sao to transform a confederation based on interpersonal relationships into a structured entity with a bureaucracy that kept her in power. As Dian Murray explains, “Although [Zheng Yi Sao] used her marriage as an access to power, her own abilities maintained it thereafter.” [27] Zheng Yi Sao’s ability to convert power which she gained through interpersonal, gendered relationships into formal control of the Guangdong Confederation is a clear example of how she turned combinations of feminine forms with piratical work into tangible power.

Of course, the switch from relational to formal power did not entirely remove the influence of gender on Zheng Yi Sao’s career. Most notably, she continued to use Chang Pao to influence the Confederation. It is difficult to render a complete account of how her gender performance interfaced with the period of her life in which Zheng Yi Sao reached peak power, but two interesting issues emerge that can be explored in relation to gender: the treatment of women in her legal codes and the relationship between her gender and the violence of the organization she led.[28]

The legal codes Zheng Yi Sao implemented for the Confederation are interesting in many ways. Some scholars interpret their emphasis on fair division of plunder and protection for women as evidence of an ideological egalitarianism.[29] Notably, the codes also reveal Zheng Yi Sao’s belief that regulated romantic and sexual relationships were intrinsically linked to the smooth functioning of the Confederation. A rose-colored view might see the rules mandating capital punishment for rape and requiring men to remain faithful to captives as proto-feminism. However, provisions calling for the execution of participants in consensual extramarital sex show that these regulations were primarily aimed at keeping order on the ship by controlling personal relationships, reflecting a belief that unregulated romantic and sexual dynamics threatened stability.[30] As Laura Duncombe writes, Zheng Yi Sao “viewed sex as a distraction that kept men from focusing on their jobs.” [31]

The codes, though structured, reflect the violent nature of the Confederation that extended beyond life on deck. Charlie Harris summarizes the violence that formed the core of Zheng Yi Sao’s piratical reputation:

To proactively cultivate a violent mystique, the pirates would drink an explosive combination of wine and gunpowder before sailing into battle… When the pirates captured naval vessels, they would execute even those who had surrendered – apparently by chopping them into small pieces, which would then be thrown overboard. On occasion, they would preface this by nailing their victims’ feet to the decks of their ship. Unsurprisingly, the pirates’ vicious reputation preceded them across the South China Coast.[32]

These practices were not mere rumor or superstition among a terrified Chinese coastal population. Writings from European mariners and merchants captured by the confederation give us a firsthand account of the group’s highly theatrical violence, including disembowelment and consumption of human hearts.[33] The extreme contrast between what would have been expected of Zheng Yi Sao as a woman versus how she operated as a pirate leader served to make her reputation all the more frightening. Dian Murray notes that Zheng Yi Sao “perhaps playing on male fear of her ‘mysterious potency,’ forced government officials to come to terms with her in effecting a settlement.” [34] If this held true for Zheng Yi Sao’s surrender, it was certainly the case for her preceding career. Under her command, the Guangdong Confederation terrorized the coast, besting Chinese, British, and Portuguese ships and even traveling further into mainland China via rivers.[35] Zheng Yi Sao planned and perhaps fought in attacks, cultivating a vicious image made all the more mystical and terrifying by its incongruence with traditional images of Confucian femininity. Zheng Yi Sao’s performance of piratical violence as a woman and her role as “commander-in-chief of the confederation” who “overpower[ed] the provincial navy and challenge[ed] fortresses on land” was a way to assert both reputational and tangible dominance. Her actions were so formidable that Chinese admirals feared venturing to sea..[36]

Surrender and Retirement

Zheng Yi Sao brought both her violent reputation and a deliberate emphasis on her identity as a woman to surrender negotiations, further merging feminine gender performance with piracy and the accompanying reputation for gratuitous, performative violence. Of all the glimpses into Zheng Yi Sao’s career, her surrender offers perhaps the clearest evidence that she knew how to manipulate situations to her advantage through the conscious performance of femininity. Surrender negotiations with the Chinese government began after factionalism threatened the Confederation’s stability, but quickly reached a stalemate when the government refused to let the Confederation members retain their wealth and ships. Both Chang Pao and Zheng Yi Sao insisted on keeping a smaller fleet of 80 ships with 5,000 crew members, plus 40 ships for salt trading.[37] Zheng Yi Sao broke this deadlock by going to the governor-general in Canton unarmed with a number of wives and children in the confederation on April 8, 1810.[38] Taking a step away from her husband and the male officials who worked under her, she presented a feminine image when reopening negotiations. Duncombe suggests that arriving unarmed was a way of “[letting] her powerful track record speak for her,” [39] while Kwan believes Zheng Yi Sao thought that Chinese officials may “panic” if they saw an armed fleet arrive with her.[40] The use of her femininity is not the only reason for Zheng Yi Sao’s successful surrender; the mere threat of her return to piracy ultimately forced the hand of Chinese officials into giving her what she wanted.[41] Yet her choice to meet the governor with women and children after the failure of Chang Pao’s negotiations in February 1810 is perhaps evidence that she approached surrender as not just a pirate but a woman and a wife, securing a position for her husband in the military while surrendering on terms that were highly favorable to members of the confederation in general.

Just as she had gained power through marriage, so too did Zheng Yi Sao set up a successful life after piracy in part through marriage, negotiating a high-ranking military position for Chang Pao and using her status as an official’s wife to claim its benefits.[42] Following Chang Pao’s death in 1822, Zheng Yi Sao continued to use her status as a widow and mother to seek advancement. In 1840, she used her marriage to Chang Pao to charge an official with embezzlement from her long-deceased husband. Additionally, she used her role as a mother to her and Chang Pao’s son (born 1811) to “raise [him] to be a better official than his father.”[43]

Zheng Yi Sao continued using gender roles as a survival tactic until her death in 1844, at age 69. After Chang Pao’s death, stories suggest she ran either a gambling house or a brothel, a lucrative job for women seeking economic prosperity.[44] Perhaps the most remarkable signal of Zheng Yi Sao’s successful career is that she died of old age and not from the dangers of piracy, an accomplishment that may well have been affected by the tactics she used in surrendering, among which her April 8, 1810 performance of gender, discussed above, stands out.

Any investigation of Zheng Yi Sao raises more questions than answers. Fully understanding how she used gender as a strategy for advancement would require speculation about her inner thoughts. There is far too much we may never know about her, including her real name (Zheng Yi Sao translates to “wife of Zheng Yi”). However, she remains a fascinating figure, not least because she was able to transform her gender into a strategic advantage by merging wifehood with power, femininity with violence, and performance with strategy.

Zheng Yi Sao was not a feminist figure, nor do I suggest that she was a proponent of women’s empowerment.[45] She was a proponent of her own empowerment, able to turn her identity as a woman to her advantage. Zheng Yi Sao’s path to power was not, at its foundation, an abnormal route for a Chinese woman of the period to take. However, Zheng Yi Sao’s ability to use gender as a springboard and a tool to build and maintain the powerful organization she led, an organization that was truly astounding in scale and effectiveness within the history of East Asian piracy, was exceptional and merits careful attention. Zheng Yi Sao negotiated piratical leadership as a woman and as a person on the margins through a mix of preexisting social channels available to her while pushing and breaking the boundaries of gender, thus creating new points of access to power and solidifying her legacy as a markedly powerful and subversive leader.

Maya Jan Mackey is a senior at the University of Texas at Austin pursuing a BA in Plan II Honors, history, and government. She is currently completing her thesis on the Attica Prison Uprising. While completing her undergraduate degree, she has been involved in research on American social movements, gender and politics, the social impact of conspiracy theories, and the history of race. She looks forward to attending law school in pursuit of studying Constitutional and civil rights law.

Acknowledgements: This article originates in Dr. Adam Clulow’s undergraduate seminar on the history of East Asian piracy

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

[1] One significant exception is the work of the Dian Murray. Murray, Dian. “One Woman’s Rise to Power: Cheng I’s Wife and the Pirates,” Historical Reflections, Vol. 8, No. 3(1981), 148, www.jstor.org/stable/41298765

[2] Duncombe, Laura S. “The Most Successful Pirate of All Time,” in Pirate Women: The Princesses, Prostitutes, and Privateers Who Ruled The Seven Seas (Chicago: Chicago Review Press Incorporated, 2017), 180-181.

[3] Murray, Dian. “Cheng I Sao in Fact and Fiction,” in Bold in Her Breeches: Woman Pirates Across the Ages, ed. Jo Stanley (Elmhurst: Pandora Publishing House, 1995), 206.

[4] See, for example, Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1990).

[5] Murray, “Fact and Fiction,” 209-210.

[6] Kwan, Nathan. “In the Business of Piracy: Entrepreneurial Women Among Chinese Pirates in the Mid-Nineteenth Century,” in Female Entrepreneurs in the Long Nineteenth Century, eds. Jennifer Aston & Catherine Bishop (Camden: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 199-201. See also MacKay, Joseph, “Pirate Nations in Maritime Societies,” Social Science History, vol. 37, no. 4 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), www.jstor.org/stable/24 573942 for a discussion of the Guangdong Confederation as an escape society that was explicitly anti-state in nature and how this may have arisen from the marginal society Zheng Yi Sao came from.

[7] Kwan, “Business of Piracy,” 199-201.

[8] Kwan, “Business of Piracy,” 197.

[9] Harris, Charlie. “Ching Shih and the Pirates of the South China Coats: Shifting Alliances, Strategy, and Reputational Racketeering at the Start of the 19th Century,” in Global History of Capitalism Project Case Studies, ed. Christopher McKenna (Oxford: Oxford Centre for Global History, 2021), 4.

[10] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 149.

[11] Murray, “Fact and Fiction,” 210.

[12] Harris, “Ching Shih and the Pirates,” 8.

[13] Harris, “Ching Shih and the Pirates,” 8.

[14] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 149.

[15] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 147-148.

[16] Kwan, “Business of Piracy,” 199-201.

[17] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 148.

[18] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 150.

[19] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 150.

[20] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 150.

[21] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 159.

[22] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 151.

[23] It is worth noting that there is some debate as to the degree to which Chang Pao himself created these legal codes, yet the admittedly limited scholarship there is on his relationship with Zheng Yi Sao tends to take the position that she exerted a significant amount of influence on him and therefore played a significant role in the formation of these codes. Though sources may attribute these codes to either one of the couple, Zheng Yi Sao’s influence is present. For more on this debate, see Duncombe, “Most Successful Pirate,” 178-179.

[24] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 159.

[25] Harris, “Ching Shih and the Pirates,” 10.

[26] Murray, “Fact and Fiction,” 210-211.

[27] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 160.

[28] A minor speculative point also emerges from the fact that at the time, running brothels was a heavily female profession that allowed women a way to enter the Chinese economy, as Nathan Kwan notes (“Business of Piracy,” 211). There is no evidence that Zheng Yi Sao led a brothel, but the possibility that her background in sex work influenced her financial management skills as well as her attitudes towards the capture, ransoming, and selling of women as part of the operations of the Guangdong Confederation. This point requires more evidence and analysis that will not be undertaken here, and we may never know the answer, but the possibility that Zheng Yi Sao’s sex work contributed more to her piratical career than just the opportunity to meet Zheng Yi is one with fascinating implications for the discussion of gender and piracy at hand.

[29] Both Joseph MacKay and Nathan Kwan seem to support ideological or egalitarian readings of the confederation. See MacKay, “Escape Societies,” 564-566; Kwan, “Business of Piracy,” 201.

[30] Duncombe, “Most Successful Pirate,” 178.

[31] Duncombe, “Most Successful Pirate,” 178.

[32] Harris, “Ching Shih and the Pirates,” 5.

[33] Murray, “Fact and Fiction,” 230.

[34] Murray, “Fact and Fiction,” 207.

[35] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 156-157; Harris, “Ching Shih and the Pirates,” 10.

[36] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 154-155.

[37] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 158.

[38] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 157-158.

[39] Duncombe, “Most Successful Pirate,” 179.

[40] Kwan, “Business of Piracy,” 196.

[41] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 158.

[42] Since she remarried to Chang Pao after the death of her first husband, Zheng Yi Sao should not have been able to access these benefits. We do not know the details of how she prevailed, but she was seemingly successful in her petition to the government to be able to use the title and accompanying privileges. Murray, “Rise to Power,” 159.

[43] Murray, “Rise to Power,” 159.

[44] Duncombe, “Most Successful Pirate,” 180; Kwan, “Business of Piracy,” 211.

[45] Duncombe, “Most Successful Pirate,” 178; Murray, “Fact and Fiction,” 230-231.