By Blake Scott and Andres Lombana-Bermudez

A new documentary film series.

This short film tells the migration story of the Emberá indigenous community, Parara Puru, and how the community entered into Panama’s tourism industry.

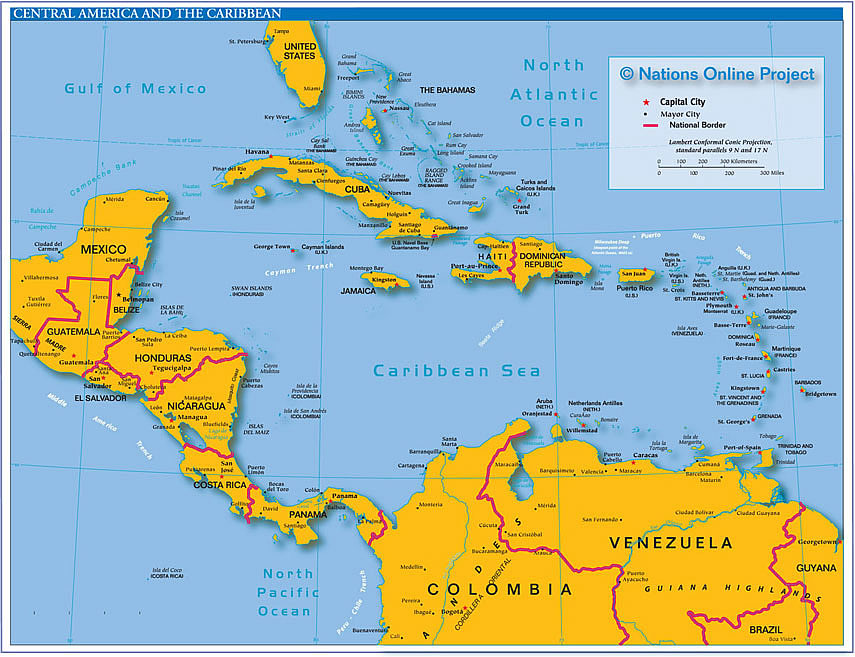

“The past is never dead,” as William Faulkner and this website remind us, “It’s not even past.” We explore the endurance of the past in the present through ethnographic filmmaking. In January 2013, we traveled to Panama to observe and participate in the country’s growing tourism industry. We met with guides, tourists, entrepreneurs, maids, hustlers, retirees, and a whole lot of beautiful and very complicated human beings. The documentary film series, I am tourism/ Yo soy turismo sheds light on the personal histories that make up contemporary tourism in Panama and the Caribbean.

[jwplayer player=”2″ mediaid=”4962″]

This short video is the beginning of the documentary project. This semester we will be revising this first video and working on another short film focused on the cruise ship industry in the Caribbean city of Colon. Our goal is to create a series of short films that can serve as an educational resource for students of tourism, history, and cross-cultural exchange.

Chagres National Park in Panama (Ecotourism in Panama)

If you have any feedback or comments, or would like to learn more about the project, please let us know.

For more information on the history and culture of the Emberá in Panama:

“Indigenous Land and Environmental Conflicts in Panama: Neoliberal Multiculturalism, Changing Legislation, and Human Rights,” by Julie Velásquez Runk, Journal of Latin American Geography, Volume 11, Number 2, 2012,

pp. 21-47.

“Emberá Indigenous Tourism and the Trap of Authenticity: Beyond Inauthenticity and Invention,” by Dimitrios Theodossopoulos, Anthropological Quarterly, Volume 86, Number 2, Spring 2013, pp. 397-425.

To learn about the Panama Canal and its role in Panamanian History:

The Canal Builders: Making America’s Empire at the Panama Canal by Julie Greene

The Panama Canal: The Crisis in Historical Perspective by Walter LaFeber

More documentaries about Panama, the Canal, and Tourism:

Panama Deception, by Barbara Trent

Paraiso for Sale, by Anayansi Prado

You may also like Jonathan Brown’s piece about LBJ’s fascinating conversation with the Panamanian President: A Rare Phone Call from One President to Another

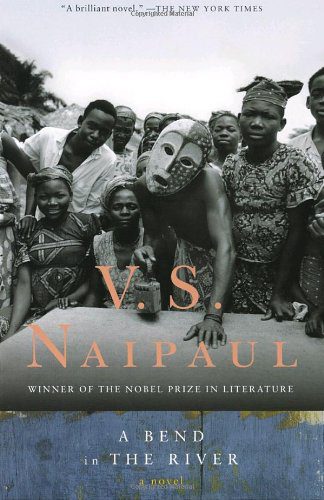

Much like its eponymous waterway, V.S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River meanders steadily through the dark reality of postcolonial Africa, alternately depicting minimalist beauty and frightening tension. Like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, subtle prose reveals the timelessness of the continent’s remote corners alongside human corruptibility. Yet, Naipaul moves his narrative closer in time to contemporary Africa, demonstrating that the horrifying legacies of colonialism did not end with Europe’s retreat. In A Bend in the River, the struggle to establish national identities in the wake of Western imperialism takes center stage, with “black men assuming the lies of white men” in order to govern.

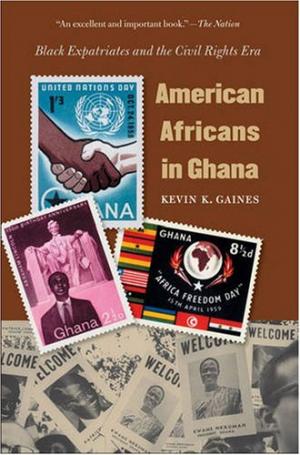

Much like its eponymous waterway, V.S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River meanders steadily through the dark reality of postcolonial Africa, alternately depicting minimalist beauty and frightening tension. Like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, subtle prose reveals the timelessness of the continent’s remote corners alongside human corruptibility. Yet, Naipaul moves his narrative closer in time to contemporary Africa, demonstrating that the horrifying legacies of colonialism did not end with Europe’s retreat. In A Bend in the River, the struggle to establish national identities in the wake of Western imperialism takes center stage, with “black men assuming the lies of white men” in order to govern. His references to Gandhi and the fall of the Berlin Wall evoked powerful images for most Americans, but Obama’s allusion to the small West African nation of Ghana may be less familiar. Yet in 1957, Ghana’s peaceful transition to independence heralded the end of European colonialism and served as an inspiration to oppressed peoples throughout the world. Kevin Gaines’ American Africans in Ghana recovers the symbolic role that the young nation played in the African American freedom struggle, and the reasons why it stirred

His references to Gandhi and the fall of the Berlin Wall evoked powerful images for most Americans, but Obama’s allusion to the small West African nation of Ghana may be less familiar. Yet in 1957, Ghana’s peaceful transition to independence heralded the end of European colonialism and served as an inspiration to oppressed peoples throughout the world. Kevin Gaines’ American Africans in Ghana recovers the symbolic role that the young nation played in the African American freedom struggle, and the reasons why it stirred