At first look, Barbara Kalish fit the stereotype of the 1950s wife and mother. In 1947, at age eighteen, Barbara met and married a sailor who had recently returned home from the war. The couple bought a house in suburban Norwalk, California and had two daughters. While her husband financially supported the family, Barbara joined the local Democratic club and the PTA. Yet beneath the surface, Barbara’s picture-perfect life was more complicated. Soon after marrying, Barbara realized she had made a mistake. She called her mother asking to return home, but was told, “You’ve made your bed. Lie in it.” Divorce was not an option, so Barbara persevered. Eventually, through the PTA she met Pearl, another wife and mother who lived only a few blocks away. Though Barbara had never before been conscious of same-sex desires, she thought Pearl “the most gorgeous woman in the world” and fell madly in love. In an oral history interview recorded years later, Barbara could not recall exactly how it happened, but somehow she was able to tell Pearl that she loved her and the women began an affair that continued for more than a decade.

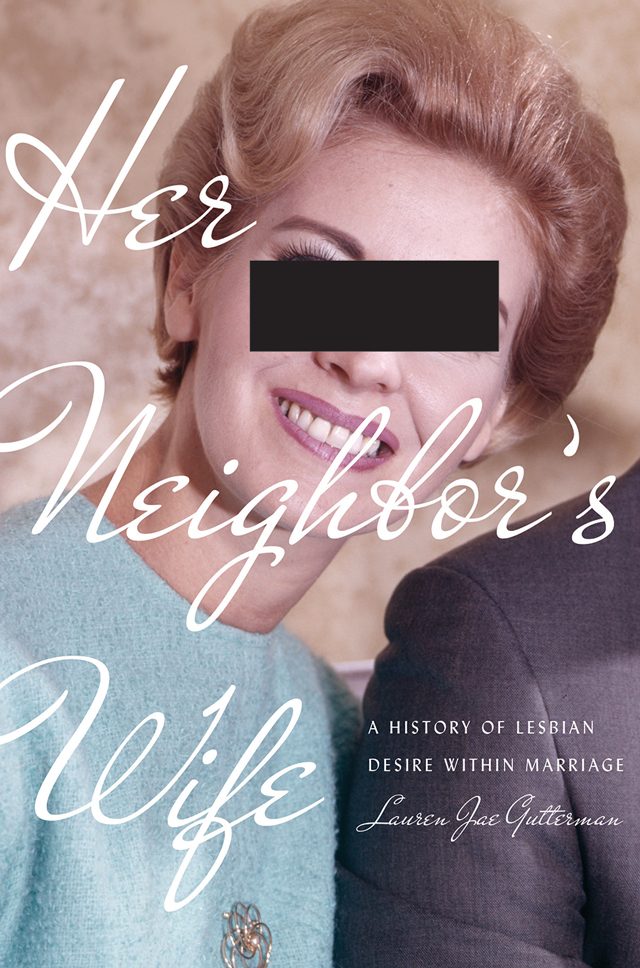

Her Neighbor’s Wife: A History of Lesbian Desire Within Marriage centers on women like Barbara who struggled to balance marriage and same-sex desires in the second half of the twentieth century. Many—if not most—women who experienced lesbian desires during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s were married at some point, yet this population has been neglected in histories of gay and lesbian life, as well as histories of marriage and the family. Focusing on the period between 1945 and 1989, Her Neighbor’s Wife is the first historical study to focus on the personal experiences and public representation of wives who sexually desired women. Through interviews, diaries, memoirs and letters, the book documents the lives of more than three hundred wives of different races, classes, and geographic regions. These women serve as a unique lens through which to view changes in marriage, heterosexuality, and homosexuality in the post-World War II United States.

To a remarkable degree, the wives in this study were able to create space for their same-sex desires within marriage. Historians have typically categorized men or women who passed as straight while secretly carrying on gay or lesbian relationships as leading “double lives.” This concept may describe the experiences of married men who had anonymous homosexual encounters far from home, but it fails to capture the unique experiences of married women who tended to engage in affairs with other wives and mothers they met in the context of their daily lives: at church, at work, or in their local neighborhood. Barbara and Pearl, for instance, lived mere blocks away from each other. They socialized together with their husbands and children, went on trips together, and even ran a business together for many years. While LGBT history has focused on queer bars in urban spaces, many wives who desired other women found ample opportunity to engage in sexual relationships with other women in their own homes in their husbands’ absence. Some of these men remained unaware of their wives’ same-sex relationships, but others chose to turn a blind eye to their wives’ affairs and waited for them to pass.

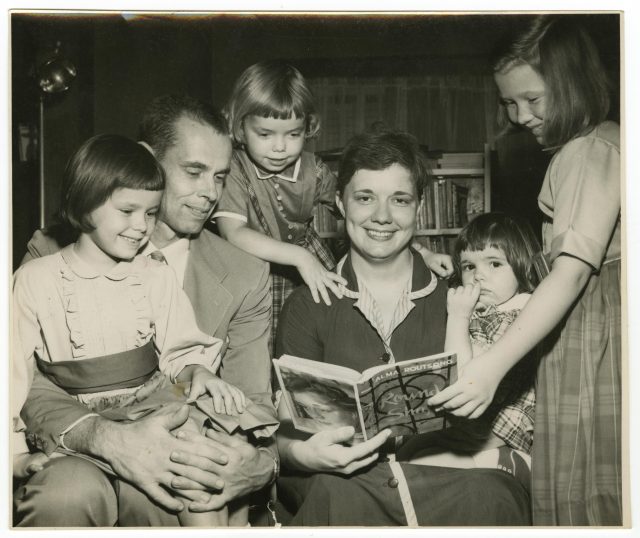

Alma Routsong and her family in a press photo for her novel Round Shape, 1959. Routsong carried on a relationship with another woman for a year in Champaign, Illinois, in the early 1960s before divorcing her husband. Curt Beamer for the News-Gazette. (From the Isabel Miller Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Libraries.)

Lesbian history has highlighted the politically radical implications of love and sex between women, but married women’s same-sex affairs did not always function as a type of resistance to or protest against the institutions of heterosexuality and marriage. In some cases, engaging in same-sex relationships within marriage propelled women to identify as lesbians and to leave their marriages. This was a path, and a choice, that became increasingly available to (and expected of) women across this book’s time period as divorce became more common, and gay and lesbian activists challenged the stigmatization of homosexuality. However, many wives’ ambivalence about labeling themselves or their affairs as lesbian, and their refusal to divorce well into the 1980s and beyond, challenge a simplistic interpretation of such wives’ desires and identities. While the emergence of no-fault divorce, gay liberation, and lesbian feminism made it possible for many wives to leave unhappy marriages and build new lives with other women, others experienced the growing division between married and lesbian worlds as constraining, as forcing a choice they did not have to make before.

Della Sofronski dressed for a neighborhood Halloween party in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, which she and her lover attended in costume as husband and wife, ca. 1945. (From the private collection of Kenneth Sofronski.)

Barbara and Pearl’s story reveals how women responded differently to the social and cultural transformations of the 1970s. During their many years together, Barbara and Pearl had secretly planned to leave their marriages once their children were grown. Around 1970, when Barbara was forty and her daughters were in high school, she decided she was ready to leave her marriage and begin her life with Pearl. But Pearl did not want to divorce. She was ill at the time and worried about losing health insurance if she left her husband, a man Barbara described as “a sweet guy.” So Pearl remained married, and Barbara divorced. “I went to Chuck Kalish and said, ‘I’m going.’ And I went,” she recalled. By this time Barbara had discovered the Star Room, a lesbian bar in Los Angeles. In fact, Barbara invested some of her own money in the bar, making her a part owner, and when she left her marriage she moved into a house directly behind the bar where she easily embarked on a new lesbian life. “I was in hog heaven,” Barbara later said.

Like Barbara and Pearl, the wives described in Her Neighbor’s Wife made a range of choices over the course of their lives. Some ended their lesbian relationships and remained married for good. Some experimented with “open” or “bisexual” marriages in the era of the sexual revolution. Yet others divorced their husbands in order to pursue openly lesbian lives. Whatever paths they took, however, the wives in this study suggest that marriage in the postwar period was not nearly as straight as it seemed.

Further reading:

Rachel Hope Cleves, Charity and Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America (2014). Using diaries and letters Cleves uncovers a more than forty-year relationship between two women, Charity Bryant and Sylvia Drake, in nineteenth century New England. Bryant and Drake’s family and community members recognized their relationship as a marriage, thus challenging the notion that same-sex marriage is a new invention without historical precedent.

Clayton Howard, The Closet and the Cul-de-Sac: The Politics of Sexual Privacy in Northern California (2019). Focusing on the San Francisco Bay Area, Howard’s book explains how suburban development practices and federal housing policies privileged married home buyers and sought to protect their sexual privacy in the postwar period. Suburbanization, Howard shows, built sexual segregation—between married couples and sexually non-normative others—into the geographic division between urban and suburban areas.

Heather Murray, Not in This Family: Gays and the Meaning of Kinship in Postwar North America (2010). Not in This Family traces shifting relationships between gays and lesbians and their parents between the immediate postwar period and the era of gay and lesbian liberation. Murray examines the central role of biological family ties in gay and lesbian politics and charts how “coming out” to one’s parents became an expected rite of gay and lesbian identification.

Daniel Winunwe Rivers, Radical Relations: Lesbian Mothers, Gay Fathers, and Their Children in the United States since World War II (2015). Rivers challenges understandings of parents and the family as exclusively heterosexual. His book shows how gay and lesbian parents raised their children, often within the context of heterosexual marriages, in the postwar period, before fighting for child custody in brutal family court battles of the 1970s and 1980s.

Top image: Della Sofronski and her family on vacation, ca. 1945. From the private collection of Kenneth Sofronski.