by Jessica Wolcott Luther

The original story of Yarico is from Richard Ligon’s 1657, A True and Exact History of Barbados:

This Indian dwelling neer the Sea-coast, upon the Main, an English ship put in to a Bay, and sent some of her men a shoar, to try what victualls or water they could finde, for in some distresse they were:

But the Indians perceiving them to go up so far into the Country, as they were sure they could not make a safe retreat, intercepted them in their return, and fell upon them, chasing them into a Wood, and being dispersed there, some were taken, and some kill’d:

but a young man amongst them stragling from the rest, was met by this Indian Maid, who upon the first sight fell in love with him, and hid him close from her Countrymen (the Indians) in a Cave, and there fed him, till they could safely go down to the shoar, where the ship lay at anchor, expecting the return of their friends.

But at last, seeing them upon the shoar, sent the long-Boat for them, took them aboard, and brought them away. But the youth, when he came ashoar in the Barbadoes, forgot the kindnesse of the poor maid, that had ventured her life for his safety, and sold her for a slave, who was as free born as he: And so poor Yarico for her love, lost her liberty.

Ligon’s work was the only comprehensive text published about the English Caribbean throughout the entire seventeenth century. His text was widely read and often quoted. There is no indication from Ligon’s text if his account of Yarico is based on actual people or simply an allegory for how the English treated the native Carib people on Barbados.

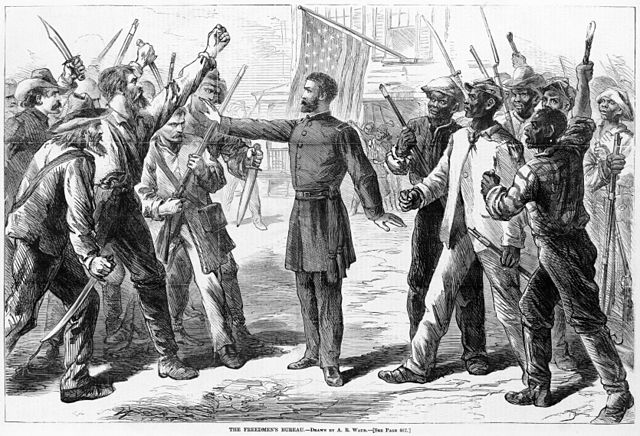

S. Hutchinson, 1793 © National Maritime Museum Collections

S. Hutchinson, 1793 © National Maritime Museum Collections

Richard Steele, an author and editor of the daily publication The Spectator, picked up the story in 1711 (issue 11 on March 13, 1711). He expanded and elaborated it into the version that became popular during the eighteenth and into the nineteenth century.

In his version, he names the Englishman Inkle and describes him as a 20-year-old who was schooled by his father early in life in the “love of gain.” The ship, on its way to Barbados, came under some distress and “put into a Creek on the Main in America, in search of provisions.” There, he met Yarico.

They appeared mutually agreeable to each other. If the European was highly charmed with the Limbs, Features, and wild Graces of the Naked American; the American was no less taken with the Dress, Complexion, and Shape of an European, covered from Head to Foot. The Indian grew immediately enamoured of him, and consequently solicitous for his Preservation.

She hid him and cared for him. “In this manner did the Lovers pass away their Time, till they had learn’d a Language of their own.” They lived this way for a few months. Then Yarico, instructed by Inkle, flagged down a shipped on the coast. When they found out it was traveling to Barbados, Inkle was ecstatic.

It ends thusly:

To be short, Mr. Thomas Inkle, now coming into English territories, began seriously to reflect upon his loss of Time, and to weigh with himself how many Days Interest of his Mony he had lost during his stay with Yarico. This Thought made the Young Man very pensive, and careful what Account he should be able to give his Friends of his Voyage. Upon which considerations, the prudent and frugal young Man sold Yarico to a Barbadian merchant; notwithstanding that the poor Girl, to incline him to commiserate her Condition, told him that she was with Child be him: But he only made use of that Information, to rise in his Demands upon the Purchaser.

Over the course of the eighteenth century, at least 60 versions of the story were published and there were a number of translations (according to Frank Felsenstein). It was made into an opera, a play, rendered in the form of a poem, and was retold many, many times.

While we will never know the veracity of this particular story about this particular indigenous woman (though it’s fair to say that Steele’s additions were fictitious), it does tell us a lot about how the British thought about hierarchy, gender, and the fraught relationship between the British and the people that they enslaved. Yarico shows that from some of the earliest decades of English settlement, there was an uneasiness about the exploitation of other people and the easy slippage between “free” and “enslaved.”

Also, it draws attention specifically to the plight of enslaved women. Yarico’s tale shows how complicated personal relationships were (and are) in a society were power is so unequally distributed. One cannot doubt that there would have been many an enslaved African or indigenous woman sold into slavery by men who had shown them affection, even love. Steele’s version in particular lays bare the almost unimaginable reality in the life of an enslaved woman: her dual role of producer and re-producer, her value was as much in her ability to do the work of a male slave as in the ability of her body to reproduce the next generation of slaves.

You may also enjoy:

Zach Doleshal’s podcast interview with Jessica Luther