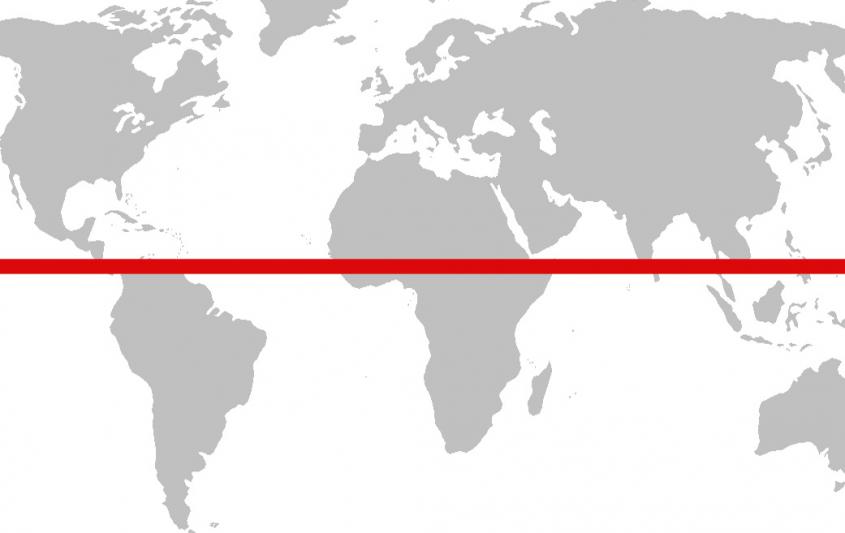

There exists a fault line near the tenth parallel north of the equator where the two great proselytizing religions of the last two millennia meet. In centuries past, desert traders and merchant seamen carried Islam along with their goods, halting only where they confronted unsurpassable natural barriers or the expansion of European Christianity in the colonized regions of Asia and Africa. The diverse peoples of these lands found ways to live alongside each other, yet the past decades have seen this relative peace come unglued. New Yorker reporter and poet Eliza Griswold traveled along this increasingly chaotic border, documenting the day-to-day realities of the growing conflicts between the world’s largest monotheistic faiths. She finds that more than mere ideology motivates these men and women; instead, “growing numbers of people and an increasingly vulnerable environment are sharpening the tensions between Christians and Muslims over land, food, oil, and water.”

In Nigeria, Sudan, Malaysia, the Philippines, and elsewhere, Griswold reveals that religious identity serves as a refuge from the constant challenges of the modern way of life. Climate change, the expansion of the nation state in search of natural resources, political conflict, and the globalization of the market economy all undermine traditional beliefs that rely heavily on local community and close association with the environment. Colonial legacies and ethnic differences have inspired deep political divides.

In Nigeria, Sudan, Malaysia, the Philippines, and elsewhere, Griswold reveals that religious identity serves as a refuge from the constant challenges of the modern way of life. Climate change, the expansion of the nation state in search of natural resources, political conflict, and the globalization of the market economy all undermine traditional beliefs that rely heavily on local community and close association with the environment. Colonial legacies and ethnic differences have inspired deep political divides.

In these developing countries, state institutions and social organization often lag behind economic growth and fail to fill the place of ailing traditions. Here, religious community provides stability and scripture proves “a more practical rule of law than the government does.” Faith offers a support network, a form of advocacy, and a unifying identity where life is difficult and the control of valuable resources contentious. The transnational nature of both Christianity and Islam means that these parochial negotiations of power often invite foreign assistance from evangelical missionaries and radical Islamists with their own agendas, meaning that battles are “fought locally and exploited globally.” The ease of communication and common beliefs connect disparate peoples, but such interactions also work to inspire divisions among coreligionists who reject the perceived superficiality and wickedness of the more secularized spiritual practices of developed states. Griswold finds that both Christianity and Islam prove complicated beliefs, neither inherently contradictory nor monolithic, powerful stabilizing forces abused by self-interested leaders. Faith in this context becomes a coping mechanism for unfamiliar world; it “could mean whatever one wanted it to; it could hold a link to the past or forge a vision for the future.”

In these developing countries, state institutions and social organization often lag behind economic growth and fail to fill the place of ailing traditions. Here, religious community provides stability and scripture proves “a more practical rule of law than the government does.” Faith offers a support network, a form of advocacy, and a unifying identity where life is difficult and the control of valuable resources contentious. The transnational nature of both Christianity and Islam means that these parochial negotiations of power often invite foreign assistance from evangelical missionaries and radical Islamists with their own agendas, meaning that battles are “fought locally and exploited globally.” The ease of communication and common beliefs connect disparate peoples, but such interactions also work to inspire divisions among coreligionists who reject the perceived superficiality and wickedness of the more secularized spiritual practices of developed states. Griswold finds that both Christianity and Islam prove complicated beliefs, neither inherently contradictory nor monolithic, powerful stabilizing forces abused by self-interested leaders. Faith in this context becomes a coping mechanism for unfamiliar world; it “could mean whatever one wanted it to; it could hold a link to the past or forge a vision for the future.”

Displaced Persons camp in Sudan resulting from the conflict in Darfur.

Displaced Persons camp in Sudan resulting from the conflict in Darfur.

Griswold offers a fascinating, poignant, and insightful account of global religious conflict. Part history, part travelogue, and part theological mediation, the work successfully dissects the “compound of multiple identities” that drives the mass conversion of whole populations and motivates pious believers to take up arms against their neighbors. The daughter of Episcopal bishop Frank Griswold, the author situates this discussion of devotional violence within the context of her own spirituality, offering a personal and accessible view of a highly charged subject. Her pithy, graceful writing clothes this complicated story in an understated elegance. The Tenth Parallel demands attention as an insightful piece of historically informed news reporting and a truly engrossing account of one woman’s theological journey across the globe.

Further reading:

Eliza Griswold discusses Christian-Muslim relations on NPR Books.

Darfur photograph via Wikimedia Commons.

Reverend Charles M. Sheldon first asked “What would Jesus Do?” in an 1896 novel entitled

Reverend Charles M. Sheldon first asked “What would Jesus Do?” in an 1896 novel entitled

His churchwarden’s accounts are laden with personal commentary, providing a unique window into the lives of ordinary men and women during the years of the English Reformation, when the Church of England first broke away from the Catholic Church in Rome. Though titled the Voices of Morebath, the voice of Sir Christopher Trychay, with all his opinions and biases, dominates the work; The Voices of Morebath is ultimately his story.

His churchwarden’s accounts are laden with personal commentary, providing a unique window into the lives of ordinary men and women during the years of the English Reformation, when the Church of England first broke away from the Catholic Church in Rome. Though titled the Voices of Morebath, the voice of Sir Christopher Trychay, with all his opinions and biases, dominates the work; The Voices of Morebath is ultimately his story.