By Mark Sheaves

On September 18 the Scottish people will vote to decide whether the country should withdraw from the United Kingdom. Over the summer the polls have swung back and forth, and as the referendum draws closer the competing campaigns have intensified. Nationalist rhetoric prevails on both sides, with historical examples deployed to either highlight injustices or moments of peaceful prosperous union. Indeed, the historical animosity felt by many Scots towards the ruling Conservative party seems to be worrying the Prime Minister, David Cameron. Demonstrating his lack of faith in the Scottish people’s decision-making faculties he urged voters last week not to break up the union just to give the “effing Tories a kick”. The history of the relationship between the two kingdoms is vital for both camps, but surely it is more complicated than historical subjection or fraternal cooperation. Exploring the millennium long relationship between England and Scotland – as George Christian also did in his NEP article last Monday – we can begin to comprehend the complicated issues at stake in this referendum and the possible ramifications. Few have tackled such a large topic, but one book that has is Norman Davies’ The Isles: A History.

On September 18 the Scottish people will vote to decide whether the country should withdraw from the United Kingdom. Over the summer the polls have swung back and forth, and as the referendum draws closer the competing campaigns have intensified. Nationalist rhetoric prevails on both sides, with historical examples deployed to either highlight injustices or moments of peaceful prosperous union. Indeed, the historical animosity felt by many Scots towards the ruling Conservative party seems to be worrying the Prime Minister, David Cameron. Demonstrating his lack of faith in the Scottish people’s decision-making faculties he urged voters last week not to break up the union just to give the “effing Tories a kick”. The history of the relationship between the two kingdoms is vital for both camps, but surely it is more complicated than historical subjection or fraternal cooperation. Exploring the millennium long relationship between England and Scotland – as George Christian also did in his NEP article last Monday – we can begin to comprehend the complicated issues at stake in this referendum and the possible ramifications. Few have tackled such a large topic, but one book that has is Norman Davies’ The Isles: A History.

Published in 1999, The Isles, traces the development of the political entities and cultural identities inhabiting the archipelagos currently divided into the nations of England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Drawing on a selection of reference works and the expertise of some specialists the book ranges from the last Ice Age to the present day. It covers the early Celtic, Germanic, Roman and Norse groups, the emergence of separate kingdoms, and the various configurations of unity running alongside the rise and fall of the British Empire. The final chapter, The Post-Imperial Isles, addresses a contemporary debate about a perceived British political and identity crisis, in the context of the devolution of the United Kingdom. Davies concludes by offering his own vision for the future, arguing that the establishment of the United Kingdom served the interests of Empire, and therefore, in a post-imperial world, each nation should exist as a distinct entity in the wider community of Europe. While Davies’ argument supports the dissolution of the United Kingdom, at over one thousand pages long The Isles is unlikely to be near the top of the yes to independence campaign’s reading list.

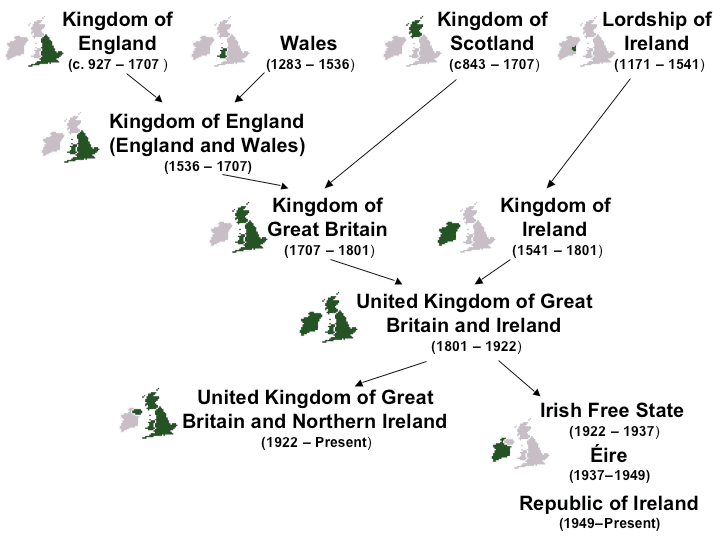

The complex relationships between the states of the British Isles from 927 to the present (Wikimedia Commons)

The Isles is a book that tries to accomplish a lot of different goals. Davies’ broad scope, incorporating a variety of historical perspectives, tackles Anglo-Centric narratives and myth-making that taints much scholarship on this subject since the “Protestant triumphalism” of the seventeenth century. The long periodization and large number of themes covered seeks to address a perceived overspecialization in the discipline of History and the lack of coherence in History teaching in schools. Quotes from primary sources lace the lively and clear narrative in an attempt to appeal to a wide readership. Engaging and informative, both academics and the public will benefit from reading the Isles, but does Davies try to do too much?

The polarized critical reception of this book in newspapers and book reviews reveals the pitfalls of adopting such an ambitious scope. Some nations receive more attention than others (Wales fares particularly badly), while certain events, such as the Irish potato famine, and themes, such as industrialization and slavery, receive short shrift. The author’s political convictions also color interpretations. Davies presents the Reformation as a moment when England cut cultural and intellectual ties with the continent, ignoring much scholarship that demonstrates the continuance of strong ties not only with Europe, but also the wider Atlantic world. Similarly, Davies ignores important insights about social revolution contained in works by eminent historians such as Eric Hobsbawm and E.P. Thompson. Finally, as result of the broad scope, the final chapters on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries attempt to condense a large number of themes and events and do not do justice to this complicated era. However, these criticisms might be unwarranted as Davies aims for a “very personal view of history.” With these shortcomings in mind, readers will find that his book introduces key themes in the history of the Isles, integrating multiple perspectives on significant historical and current issues related to the different nations and cultures. Are these differences enough to justify the end of the Union? Or are the kingdoms too entangled? The voters will decide shortly…

Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom. In Scotland, the Queen has a separate version of the Royal Arms. (Wikicommons)

Norman Davies, The Isles: A History

You may also like

George Christian, Independence for Scotland? An Historical Perspective on the Scottish Referendum

And Jack Loveridge’s review of The Decline, Revival and Fall of the British Empire